Inflation And Its Causes: How To Turn Things Upside Down – OpEd

Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS Global Wealth Management, recently said in an interview with Yahoo Finance that today’s wave of inflation is due to the greed of corporations that are seizing the moment and increasing their margins.

This position does not stand up to criticism and represents an aberration of Keynesian economic consciousness.

Donovan argues that the inflationary post-cycle consists of three waves, caused by different causes.

The first wave, according to Donovan, was driven up by the demand of the post-covian recovery.

This was followed by a second wave caused by the supply-side crisis – supply chain disruptions and the energy crisis.

Today we are in the midst of a third wave, according to Donovan, whose trigger is the desire of companies to maintain and increase profits. Donovan calls it greed-driven inflation, where consumer-oriented companies near the end of the production chain persuade customers to accept higher prices using plausible explanations (e.g., historically elevated inflation). However, according to Donovan, the real reason for these higher prices may have more to do with increasing margins and keeping investor sentiment high than with increasing production costs.

This “leftist” stance is typical and characteristic of many Keynesian economists who are unwilling to give up their illusions. It is the realization of these illusions over the past decades that has led us to the depressing global hypershifts. Failure to view the current inflation cycle as an obvious consequence of dirigist Keynesian economic policies can have unfortunate consequences.

Indeed, inflation can have various apparent causes. For example, inflation, on the face of it, may be triggered by demand or supply. It is true that the market is cyclical, but if market relations are not distorted by “state care,” a balance will be found more or less quickly. But this is not even the issue today: the government and the FED are the main drivers of the economic behavior of agents.

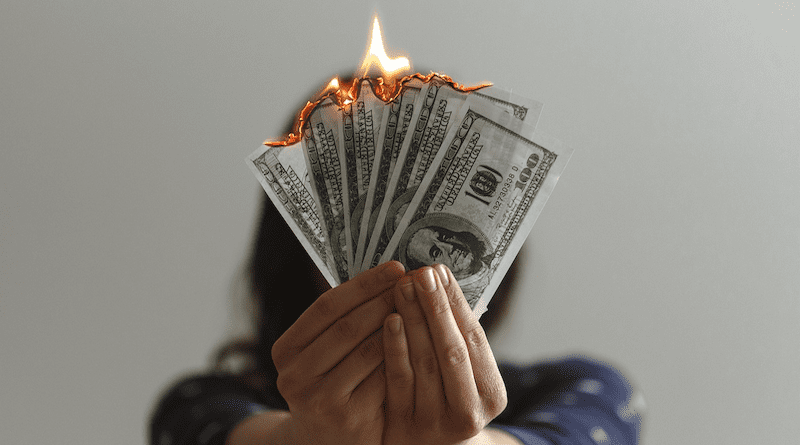

What is clear is that in today’s world, the root of all inflation is the same: it is the monetary and fiscal policies of the state, not market supply and demand deviations.

The relentless expansion of credit distorts both consumer and production preferences. Consumers plan their consumption based on the easy availability of money, while producers plan their investments and capacity utilization based on the constant growth of consumer demand and cheap credit. This applies not only to national producers, but also to global producers who serve the consumer demands of developed countries.

Of course, when the “easy money” system breaks down and demand begins to outstrip supply, inflationary pressures arise: there is a lot of money, few goods, and inflation rises. Obviously, rising inflation means higher prices not only for final goods, but also for production components, which inevitably increases producers’ costs and reduces their profits.

Manufacturers are forced to maneuver between being able to maintain margins and not increasing the prices of goods too much to keep them affordable. Under the dirigist economic policy paradigm, the FED does the only thing it can – it increases the lending rate and sucks liquidity out of the market, which naturally increases the cost of credit, meaning that producers’ costs rise even more. At the same time, with a significant reserve of savings and expecting high inflation in the coming year, consumers continue to consume actively, and the imbalance between supply and demand is exacerbated.

At the same time, thanks to expansive economic policies and government handouts of free money during the pandemic and the continued high level of social spending, the mass of people have chosen not to work, and the shortage of migrant labor has never been fully filled; labor shortages still exist. A tight labor market means rising wages-another shot at manufacturers, another factor in rising costs.

Finally, the government’s irrepressible appetite for increased government spending means an inevitably unfavorable fiscal and regulatory environment for manufacturers, which does not add impetus to economic growth and the intensification of business activity.

How, then, can a producer survive in the face of component inflation, continued high consumer demand, extraordinary credit rates, and a large fiscal and regulatory overhang? It should not be forgotten that manufacturers have shareholders, they have employees, and the task of business is, by definition, to increase profits, sales, and maximize margins. It is strange to reproach a business for passing costs on to consumers by increasing prices. The desire to socialize business or demand from it excessive social responsibility is simply economic absurdity.

What really needs to be done is to change the vector of a flawed economic policy based on increasing government spending, non-stop expansion of the government in the economy, and a continuous expansion of credit. In fact, that is exactly what the Republicans in the Senate have been fighting for, forcing the Biden Administration to cut government spending in exchange for raising the debt ceiling.

You have to understand that all of the economic and other (!!!) global crises that we have today and that we have been through for the past 20+ years are the consequences of government expansion. In particular, the current inflationary cycle is caused by exceptional and inadequate monetary stimulation and expansion of state participation in market processes. When an elephant walks into a china shop, he is bound to end up blowing things to smithereens.

One of the major and frankly tiresome agendas of today is the endless discussion of why the market is growing when there are so many problems: inflation is high and economic data is disappointing… These discussions are almost pointless because as long as the government and the FED are the source of economic change, everything will depend on them and so will market movements. The government has hooked the market and the economy as a whole on the monetary needle, and like any junkie, the market demands a bigger dose – a dose of liquidity. Not giving it to the market means triggering a tsunami of unprecedented magnitude, where assets and collateral will depreciate, naturally leading to a massive bank-ranch and a crisis in the insurance and pension industries.

The market believes that amid actual stagflation, with inflation at high levels and economic activity declining, the FED will be forced to add liquidity and lower the rate. At the same time, no one has any rational predictions about when and under what conditions the FED will begin to roll back its restrictive policy, because no one can know what and at what point the FED will decide to continue: to dampen inflation or stimulate economic activity through the next batch of easy money (they do not know any other way now).

Market participants can only convince themselves that the FED and the government will not allow a collapse and will give as much money as they need. As always in economics, everything is defined by expectations. The only trouble is that expectations may not meet reality. And the reality is that amid the breakdown and reconfiguration of global exchanges, the FED and the government are inevitably faced with the very choice of meeting inflation targets or keeping the economy afloat. There are no good solutions here, and the disequilibrium is provided by distortions in government economic policy.

But the market believes in a better future (what else is left to do?), asset inflation is on the rise despite the fact that producers are finding it increasingly difficult to keep profits and margins at previous levels.

Economists like Paul Donovan should be blaming inflation not on the victim – producers and businesses – but on the source of the problem – government and the FED.