The Bastille Day Fails To Live Up To Its Motto – OpEd

The Bastille Day is celebrated as the national day of France on 14 July each year. It is the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille prison on 14 July 1789, a major event of the French Revolution.

Originally built as a medieval fortress, the Bastille eventually became a state prison where political prisoners were often kept. Some prisoners were held on the direct order of the king, from which there was no appeal.

Back then, Paris was in a state of economic and political turmoil. The feudal system, although weakened had not disappeared in France. The increasingly numerous and prosperous elite of wealthy commoners—merchants, manufacturers, and professionals, often called the bourgeoisie—aspired to political power. The peasants wanted to get rid of the last vestiges of feudalism so as to acquire the full rights of landowners and to be free to increase their holdings. French participation in the American Revolution had driven the government to the brink of bankruptcy. Furthermore, France, which had 26 million inhabitants in 1789 was the most populated country of Europe. A larger population created a greater demand for food and consumer goods, which made the problem most acute of all the European countries.

Arguments for social reform began to be advanced. A revolution seemed necessary to apply the ideas of Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Rousseau. This ‘Enlightenment’ was spread among the educated classes by the many “societies of thought” that were founded at that time, especially the free masonic lodges and the Order of the Illuminati.

The French monarchy, once seen as divinely ordained, was unable to adapt to the political and societal pressures that were being exerted on it. The growing unrest forced the king, Louis XVI, to yield and reappoint reform-minded Jacques Necker as the finance minister. He also promised to convene the Estates-General, i.e., the representative assembly of the three “estates,” or orders of the realm: the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate)—which were privileged minorities—and the Third Estate, which represented the majority of the people or the commoners, on May 5, 1789. He also granted freedom of press.

The elections to the Estates-General were held between January and April 1789. It coincided with further disturbances, as the harvest of 1788 had been a bad one. The electors elected 600 deputies for the Third Estate, 300 for the nobility, and 300 for the clergy. The Estates-General met at Versailles on May 5, 1789. They were immediately divided over a fundamental issue: should they vote by head, giving the advantage to the Third Estate, or by estate, in which case the two privileged orders of the realm might outvote the third?

The deputies of the Third Estate, fearing that they would be overruled by the two privileged orders in any attempt at reform, declared the formation of the revolutionary National Assembly on June 17, signaling the end of representation based on the traditional social classes.

When royal officials locked the deputies out of their regular meeting hall on June 20, they occupied the king’s indoor tennis court and swore an oath not to disperse until they had given France a new constitution. The king grudgingly gave in and urged the nobles and the remaining clergy to join the assembly, which took the official title of National Constituent Assembly on July 9; at the same time, however, he began gathering troops to dissolve it. He also dismissed his popular Minister, Jacques Necker.

On the morning of July 14, the angry people of Paris seized weapons from the armory at the Invalides and marched in the direction of the Bastille. After a bloody round of firing, the crowd broke into the Bastille and released the seven prisoners held there. Nearly 100 French commoners died. Bernard Rene de Launay, the governor of the Bastille, was beheaded by the mob.

The taking of the Bastille signaled the beginning of the French Revolution, and it thus became a symbol of the end of the ancien régime (Old Order) in which everyone was a subject of the king of France as well as a member of an estate and province.

In the provinces, the Great Fear of July led the peasants to rise against their lords. The nobles and the bourgeois now took fright. The National Constituent Assembly could see only one way to check the peasants; on the night of August 4, 1789, it decreed the abolition of the feudal regime and of the tithe. Then on August 26 it introduced the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, proclaiming liberty, equality, the inviolability of property, and the right to resist oppression.

Articles:

1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

2. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

5. Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society. Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law, and no one may be forced to do anything not provided for by law.

6. Law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has a right to participate personally, or through his representative, in its foundation. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally eligible to all dignities and to all public positions and occupations, according to their abilities, and without distinction except that of their virtues and talents.

7. No person shall be accused, arrested, or imprisoned except in the cases and according to the forms prescribed by law. Anyone soliciting, transmitting, executing, or causing to be executed, any arbitrary order, shall be punished. But any citizen summoned or arrested in virtue of the law shall submit without delay, as resistance constitutes an offense.

8. The law shall provide for such punishments only as are strictly and obviously necessary, and no one shall suffer punishment except it be legally inflicted in virtue of a law passed and promulgated before the commission of the offense.

9. As all persons are held innocent until they shall have been declared guilty, if arrest shall be deemed indispensable, all harshness not essential to the securing of the prisoner’s person shall be severely repressed by law.

10. No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.

11. The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law.

12. The security of the rights of man and of the citizen requires public military forces. These forces are, therefore, established for the good of all and not for the personal advantage of those to whom they shall be entrusted.

13. A common contribution is essential for the maintenance of the public forces and for the cost of administration. This should be equitably distributed among all the citizens in proportion to their means.

14. All the citizens have a right to decide, either personally or by their representatives, as to the necessity of the public contribution; to grant this freely; to know to what uses it is put; and to fix the proportion, the mode of assessment and of collection and the duration of the taxes.

15. Society has the right to require of every public agent an account of his administration.

16. A society in which the observance of the law is not assured, nor the separation of powers defined, has no constitution at all.

17. Since property is an inviolable and sacred right, no one shall be deprived thereof except where public necessity, legally determined, shall clearly demand it, and then only on condition that the owner shall have been previously and equitably indemnified.

At the time of the French Revolution, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” (“Liberté, égalité, fraternité“) was one of the many mottos in use. In a December 1790 speech on the organization of the National Guards, Maximilien Robespierre, one of the most widely known, influential, and controversial figures of the French Revolution, advocated that the words “The French People” and “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” be written on uniforms and flags, but his proposal was rejected. This motto fell into disuse under the Empire, like many revolutionary symbols.

The royal family was imprisoned by the Parisians on August 10, 1792, for its counter-revolutionary activities. On September 20 a new assembly, the National Convention, convened, which on the next day proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic.

Louis XVI was judged by the Convention, condemned to death for treason, and executed on January 21, 1793. His wife Marie-Antoinette was guillotined nine months later. Over the next two years, the opposition was broken by the Reign of Terror, which entailed the arrest of at least 300,000 suspects, 17,000 of whom were sentenced to death and executed while more died in prisons or were killed without any form of trial.

As the revolutionaries got divided on policy matters, Maximilien Robespierre, “the Incorruptible,” a member of the influential Jacobin Club, who was in favor of giving more power to the downtrodden, was overthrown in the National Convention on July 27, 1794, and executed the following day.

Soon after the efforts toward economic equality were abandoned. Reaction set in; the National Convention began to debate a new constitution; a royalist “White Terror” against the Jacobins broke out throughout France. Royalists even tried to seize power in Paris but were crushed by the young Gen. Napoleon Bonaparte on October 5, 1795. A few days later the National Convention dispersed. On November 9, 1799, Napoleon became the leader of France as its ‘first consul’.

The famous motto reappeared during the Revolution of 1848 marked with a religious dimension: priests celebrated the ‘Christ-Fraternité’. When the Constitution of 1848 was drafted, the motto “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” was defined as a ‘principle’ of the Republic.

Discarded under the Second Empire, this motto finally established itself under the Third Republic, although some people still objected to it, including partisans of the Republic: solidarity was sometimes preferred to equality which implies a levelling of society, and the Christian connotation of fraternity was not accepted by everyone.

This motto appears in the constitutions of 1946 and 1958 and is today an integral part of France’s national heritage.

==-==

This year, the celebrations marking the start of the French Revolution on July 14, 1789, came at a bad time for President Emmanuel Macron. France witnessed the nation’s most serious urban violence in nearly 20 years, following the fatal police shooting of a teenager with North African roots that laid bare anger over entrenched inequality and racial discrimination. More than 100,000 police were deployed around the country to prevent a new outbreak of unrest in underprivileged neighborhoods. Macron was also booed by some members of the public as he drove down the Champs Elysees in a military car. His decision to raise the retirement age sparked months of protests this spring and has hurt his popularity ratings.

Macron’s rule has only widened the gaps between the privileged and underprivileged people of France, let alone those of the African descent . The motto ‘equality, liberty and fraternity’ has lost its real meanings. Muslim women have no liberty to dress their own way in France.

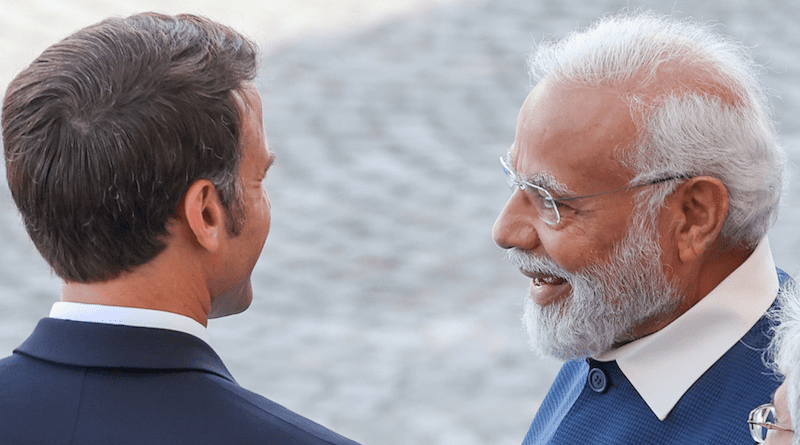

The birds of the same feather flock together. It was, thus, no surprise that the guest of honor was India’s prime minister Narendra Modi who has made a name for himself as a world leader who epitomizes inequality and discrimination. Since coming to power in 2014, Modi has passed anti-Muslim legislation and implemented anti-Muslim policies. That includes a law on citizenship and the end of the special status of Indian-administered Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority region, in 2019.

The United Nations human rights office described India’s citizenship law as “fundamentally discriminatory” for excluding Muslim migrants. So empowered are Hindu supremacists that not a single day passes by without a minority Muslim or a Christian being a target of lynching in Modi’s India.

On Thursday, July 13, Modi was granted the Legion of Honor, France’s highest award.

“(India) is a giant in the history of the world which will have a determining role in our future,” President Emmanuel Macron said in a speech late on Thursday. “It is also a strategic partner and a friend.”

France has been one of India’s closest partners in Europe for decades. It was the only Western nation not to impose sanctions on New Delhi after India conducted nuclear tests in 1998.

The Bastille parade came after New Delhi gave initial approval to buy an extra 26 Rafale jets for its navy and three Scorpene class submarines, deepening defense ties with Paris at a time the two nations are seeking allies in the Indo-Pacific.

The total value of the purchases is expected to be around $9.75 billion.

Not everyone was glad about Modi’s visit. He was criticized by human rights organizations, concerned about the growing authoritarian nature of Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party and discrimination against minorities.

“Today, Emmanuel Macron rolls out the red carpet for Narendra Modi,” the French Ligue des Droits de l’Homme (LDH) rights group said on Twitter. “The LDH, concerned about India’s authoritarian turn, denounces this invitation which sends a disastrous signal, negating our democratic values.” French leftist leader Jean-Luc Melanchon said while India was a “friendly country”, Modi was far-right leader who was “violently hostile to Muslims in his country”.

In a report in April, the Amnesty International said freedom of expression had declined under the Indian PM. Ahead of Modi’s visit, Human Rights Watch said it was “deeply concerning” that France should celebrate the idea of equality and liberty with “a leader whom many criticize for undermining democracy in India”.

The European Parliament passed a resolution on July 13 for “human rights to be integrated into all areas of the EU-India partnership, including in trade.” The resolution called on member states “to systematically and publicly raise human rights concerns” at the highest level.

Despite differences over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Western nations, including the United States, have been courting Modi and India as a military and economic counterweight to China. His two-day visit to France came on the heels of his June trip to the United States, where President Joe Biden offered Modi a lavish welcome. Modi was also recently honored in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

Well, the courting of a genocidal maniac like Modi by the world leaders from Biden to Macron to Sunak to Sisi to MBZ show the sad and ugly state of our time! Ignored are the facts that mass murderers like Modi are opposed to each of those words – equality, liberty, and fraternity.