China’s Oil Costs Climb After OPEC Deal – Analysis

By RFA

By Michael Lelyveld

As world oil prices rise, the increased costs are likely to outweigh any potential benefits for China.

Following the Nov. 30 agreement by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to cut production in January, some analysts suggested that the decision would help China and its struggling national oil companies (NOCs).

The deal to reduce OPEC output by 1.2 million barrels per day “could offer a lifeline to an industry that has been hammered by low prices—and may also hasten its shift away from a heavy reliance on Saudi crude,” The Wall Street Journal said.

Much of the logic was based on assumptions that higher prices for domestically produced oil would boost the dismal profits of China’s NOCs.

The companies’ earnings from production have slumped throughout 2016 as benchmark Brent crude dipped below U.S. $28 (193 yuan) per barrel last January and spent most of the year in the U.S. $45 (310 yuan) per barrel range.

At the PetroChina unit of China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), third-quarter profit dropped 77 percent from a year earlier to 1.2 billion yuan (U.S. $173.7 million) in a sample of the pressures on the state-owned oil monopolies.

PetroChina’s net income for the first nine months plunged 94 percent to 1.73 billion yuan (U.S. $ 250.5 million), despite a one-time gain from selling part of its pipeline business, Bloomberg News said.

The company’s oil production was down nearly 7 percent during the period from a year earlier, Bloomberg reported.

Some analysts argued that rising world prices would at least improve the profitability of China’s oil production, which fell to a seven-year low of 3.78 million barrels per day in October, according to Reuters.

But the argument appeared to ignore the impact of higher costs on China’s increasingly import-dependent oil market.

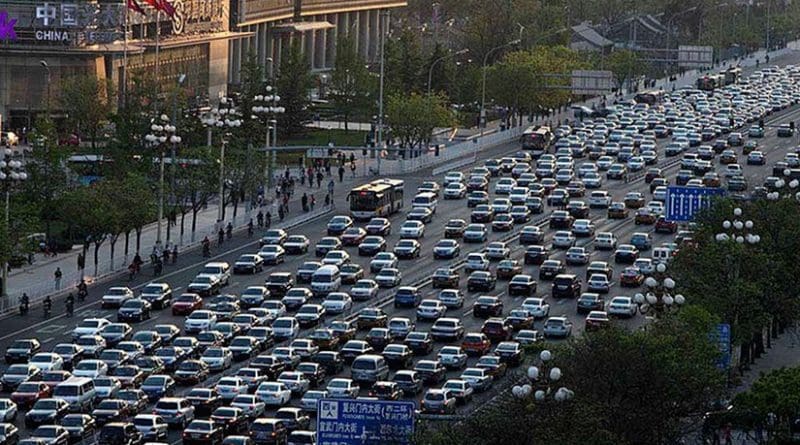

China’s imports stood at 7.87 million barrels per day in November after hitting a record high of over 8 million barrels per day in September, based on customs data.

Last month, imports were double the volume of China’s domestic production of 3.93 million barrels per day.

The heavy predominance of imports means that China’s increased costs will outweigh revenue gains from higher prices by about two-to-one.

“I can’t see how a country which is the largest crude oil importer should benefit from a deal that leads to a price increase,” said Edward Chow, senior fellow for energy and national security at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, in an email message.

Government raises gas prices

Last week, the government raised state-controlled gasoline prices by 435 yuan (U.S. $62.52) per ton, allowing a retail price hike of 0.32 yuan (U.S. $0.046) per liter, to offset some of the increased crude costs, the official English-language China Daily said.

The cost equation for China may only get worse following the agreement of 11 non-OPEC producing countries on Dec. 10 to lower output by an additional 558,000 barrels per day.

On the first trading day after the agreement, Brent crude closed up more than 3 percent to over U.S. $56 (386 yuan) per barrel, giving prices a total gain of some 20 percent since the day before the OPEC cut was announced.

Prices ended last week slightly below that level after mixed reports about compliance with production pledges and when they would take effect.

Analysts were divided between those voicing optimism that the agreements would boost prices further and those expecting that some countries would be tempted to cheat on their lower production quotas to make up for past losses.

“They are all enjoying higher prices and compliance tends to be good in the early stages. But then as prices continue to rise, compliance will erode,” said Gary Ross, founder of the consultancy PIRA Energy, quoted by Reuters.

China’s oil output has limped along for years in the range of 4 million barrels per day under the burdens of difficult geology, high production costs, depleted fields and a bloated workforce.

CNPC and second-ranked China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec) have cut back production at higher cost fields for the past year.

China’s average production costs are U.S. $40 (276 yuan) per barrel and have already risen to U.S. $45 (310 yuan) per barrel at CNPC’s standby Daqing field, an official told The Wall Street Journal earlier this year.

In its report this month, the paper described a world price range of U.S. $55-$60 (379-414 yuan) as a “sweet spot” for China that would lessen production losses without raising import costs too high.

But production cuts at ageing fields like Daqing may not be reversed unless prices rise over U.S. $60. There have been several signs that the recovery will not go that far soon.

OPEC members to cut production

The OPEC agreement, which commits countries of the 13-member cartel to start cutting production on Jan. 1, but reductions may take effect more gradually, particularly among non-OPEC producers.

Russia has promised to contribute 300,000 barrels of the cuts, or over half of non-OPEC reductions. But some industry statements have suggested reluctance to comply.

Speaking to reporters on Dec. 2, the vice president of independent oil company Lukoil, Leonid Fedun, said Russia is unlikely begin cutting before next year’s second quarter.

“Russia only starting in Q2 will most likely start to really reduce something,” Fedun said, according to Interfax.

“Technologically, this is not immediately. We don’t have a valve which can stop production,” he said.

The president of the Russian pipeline monopoly Transneft, Nikolai Tokarev, confirmed three days later that reduced output will not be seen for several months.

“The actual cut in oil production in Russia may start in March 2017,” Interfax quoted Tokarev as saying.

Some of the other non-OPEC countries that have agreed to cuts may not start actual reductions until next October, according to a report by state-controlled Russia Today.

Despite the existing oil glut, there have also been signs that Russia has ramped up production to maximize revenues from rising prices before the OPEC deal’s deadline, adding to global oversupply.

Russia plans to raise output to a record high of 11.3 million barrels per day in December, said Deputy Energy Minister Kirill Molodtsov. Energy Minister Alexander Novak gave assurances that Russia’s cut would be calculated from the November level of 11.2 million barrels per day.

The jockeying may be a sign that Russia is positioning itself both to take advantage of the short-term price hike and gain market share at Saudi Arabia’s expense. The delay in Russian cuts is likely to mean that price pressures on producers will ease only gradually.

After meeting with Russian oil companies last week, Novak gave assurances that the country would meet its reduction target by mid-2017, but he described individual company commitments as “voluntary,” the TASS news agency said.

A more substantial price rise may also encourage U.S. shale oil producers to resume production, limiting the impact of the OPEC plan.

The U.S. count of operating oil rigs rose in December for the seventh month in a row to the highest level since last January, Reuters reported, citing oil services firm Baker Hughes Inc.

Effects on China

The combination of effects on China may be mixed.

Prices may not climb to a level that would justify a restart of China’s high-cost production, while any price increase will add to the country’s import bill.

Given China’s worries about capital outflows and the depreciation of the yuan, the rising cost of oil imports is likely to be the overriding concern.

“The Chinese I met with seemed quite pleased when I told them this OPEC deal won’t stick and the price will go back down soon,” said Edward Chow, who visited China this month.

The growth of China’s oil demand this year has been surprisingly weak for a country that has reported gross domestic product growth of 6.7 percent for each of the three quarters so far in 2016.

According to Platts, China’s apparent oil demand fell 1.7 percent in the first nine months, based on official data, but the analysts estimate it actually rose 0.4 percent, considering consumption not captured by official reports.

Either way, the country’s demand growth has paled in comparison to the 5.8-percent rate that Platts estimated for last year.

The downturn in demand despite this year’s lower oil prices may add to suspicions that China’s official economic growth rates have been overstated.

China’s oil companies must improve efficiency and will be “suffering for the next few years,” said former Sinopec chairman Fu Chengyu at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, China Daily reported earlier this month.

The companies need oil prices “at least” U.S. $60 per barrel to stabilize production, Fu said.