Defense Diplomacy: Professionalizing The Purple To Gold Pipeline – Analysis

By NDU Press

By Rose P. Keravuori, Peter G. Bailey, Eric A. Swett, and William P. Duval

The Spartan Warrior, immortalized by the story of the 300 at Thermopylae, dominated the ancient Hellenistic world. While many know of the legendary Spartan training regimen, few know they were defeated through the power of Defense Diplomacy. Spartan dominance ended permanently when Epaminondas, a Theban general, used a “grand strategy of indirect approach” to establish capable partners, foster alliances, strengthen non-allied states’ defensive abilities, and decimate the “economic roots of [Sparta’s] military supremacy.”

Epaminondas’ use of officer exchanges—Philip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great’s father, spent his youth in Thebes during Epaminondas’ time and later used his tactics—high level governmental engagements, combined training, security building—the fortified city of Messene, for example—and regional security forums such as the Arcadia Alliance to advance Thebes’ interest in ending Spartan dominance—match the activities we currently call Defense Diplomacy.1

Defense Diplomacy in Action

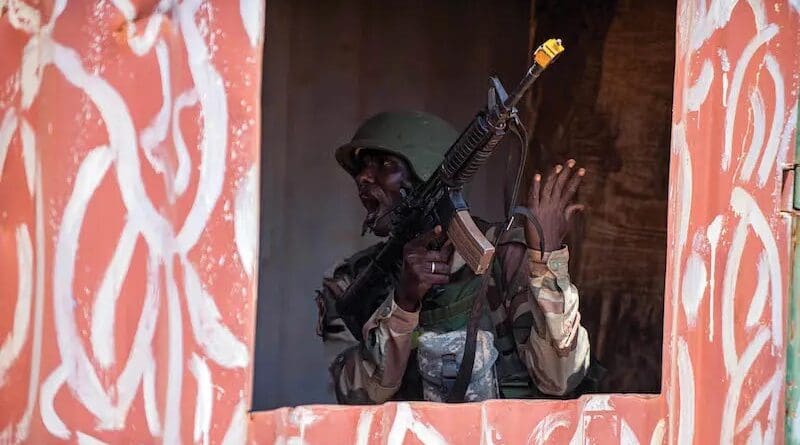

In April 2023, war broke out in Khartoum, Sudan. Suddenly, tens of thousands of Sudanese and foreign citizens became trapped between two generals vying for control of the country. Buildings were destroyed, and the streets became death zones as fighters shot at anything moving. Amid this chaos, foreign governments in Sudan, including the United States, scrambled to remove their citizens from Khartoum and the rest of the country.

U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM)’s proactive Defense Diplomacy was put to the test, ultimately helping to enable a successful operation for military-assisted departure of designated U.S. personnel and citizens from Khartoum. In support of the Department of State’s efforts, the command’s highest echelon of leadership began to engage, including the commander of USAFRICOM, General E. Michael Langley, USMC; the deputy commanding general and director of Strategy, Engagements, and Programs (J5), Major General Kenneth P. Eckman, USAF; as well as the director of Intelligence (J2), Brigadier General Jerry Carter, USMC. These three leaders established communications and personally engaged with the opposing Sudanese generals. Their direct efforts helped establish safe corridors and secure permission for the use of an airfield outside Khartoum. They also arranged safe passage corridors through checkpoints and contested territory for numerous multinational convoys from Khartoum to Port Sudan.

Even after most evacuees were safely out of Sudan, Defense Diplomacy continued to enable and support crucial humanitarian and evacuation efforts in coordination with the Department of State. Major General Eckman traveled to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to support negotiations with Sudanese delegates from both sides of the conflict to establish safety guarantees for humanitarian efforts and evacuation of noncombatant personnel.

A Core Joint Force Task

Defense Diplomacy has long been a core mission of the Department of Defense (DOD) carried out by senior military officers. Its strategic importance is repeatedly exhibited throughout history, from General George Washington’s deft diplomatic management of the colonies’ alliance with France to General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s expert management of the strong personalities of British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, French General Charles de Gaulle, and General George S. Patton to create an effective, combined force in World War II.

Congress uses a set of criteria for determining a general or flag officer position, including “official relations with other U.S. and foreign governmental positions.”2 The Joint Force Universal Joint Task List identifies engagement and building partnerships with other U.S. Government departments and agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), state and local governments, foreign partners, and humanitarian organizations as a core task at all levels of leadership.3

DOD identified the need for enhanced Defense Diplomacy professional development, and in 2010 and 2011, Congress directed the study of the “current state of interagency national security knowledge and skills” among the workforce in the National Defense Authorization Act, citing their importance for effective national security efforts.4 Shortly thereafter, the United Kingdom (UK) published its 2013 International Defence Engagement Strategy, citing engagement by UK defense leaders as critical to achieving foreign policy objectives as a central part of an integrated approach to employ “all the levers of power across government.”5

Civilian and uniformed defense leaders have long understood the interrelationship among diplomacy, development, and defense—what USAFRICOM refers to as the 3Ds—to conflict prevention and resolution. In 2017, a joint letter signed by 121 three- and four-star generals and flag officers supported the fiscal year 2018 International Affairs Budget, which resourced diplomatic and development efforts as “critical to preventing conflict.”6 When serving as the commander of U.S. Central Command, General James Mattis, USMC, reportedly stated, “if you don’t fully fund the State Department, please buy a little more ammunition for me because I’m going to need it” to emphasize the importance of an integrated whole-of-government approach to achieve security outcomes.7

The joint force increasingly operates in joint, interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational environments in which Defense Diplomacy knowledge, skills, and behaviors—derived from education and experience—provide a marked advantage.8 DOD understands the value of diplomatic and interagency experience for midcareer officers assigned to niche interagency and diplomatic specialties such as defense attachés and military advisors, but such training and experience is exceptionally rare across the joint force and among general/flag officers outside of these specialties, creating a learning curve for the vast majority who receive only familiarization-level training.9 Preparing military leadership for Defense Diplomacy with rudimentary familiarization and on-the-job training invites increased risk and decreased effectiveness of integrated deterrence and global campaigning while progressing through the learning curve of interagency coordination.

Defense Diplomacy in Africa

Defense Diplomacy is particularly beneficial in Africa due to the range of challenges, dispersed U.S. presence, and historical ties that make military-to-military engagements more salient. On official visits, general/flag officers and senior enlisted leaders from USAFRICOM often meet with African counterparts and military, diplomatic, and civil leadership above parity, elevating the level of strategic engagement with the partner country to the ministerial and occasionally presidential levels, reflective of partners’ desires for strategic engagement with the United States. As USAFRICOM leaders often play a vital role in state and nonstate negotiations, having training in or familiarity with the nuanced nature of diplomatic and development discussions becomes a necessity.

Defense Diplomacy is also a cost-effective shaping operation in “phase zero,” enhancing partner capacity, capabilities, and interoperability while promoting stability through assistance using a 3D approach.10 To better support this at USAFRICOM, foreign policy and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) advisors, embedded interagency representatives, and foreign liaison officers were deliberately built into the core staff to synchronize efforts among agencies and governments at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels.11

Increased partner engagement is the focus of the U.S. coastal West Africa and sub-Saharan strategies, and understanding African security concerns helps the United States identify how it can better support its African partners.12 With ongoing military engagements and presence in these regions—and across the continent—it becomes more important to ensure USAFRICOM and component leadership who meet with partners have the tools and training to navigate Defense Diplomacy opportunities in support of U.S. policy.

While Embassy Country Teams are responsible for coordinating whole-of-government efforts for a particular country, USAFRICOM hosts the annual Africa Strategic Dialogue, which convenes senior leaders from USAID, State, and DOD to develop a holistic 3D approach for African security challenges.13 In the following months after the Africa Strategic Dialogue, command staff, Country Teams, as well as State and USAID representatives convene for the Africa Strategic Integration Conference to coordinate layered 3D effects for specific regions, subregions, and countries.14

Unfortunately, even the best force structure can only marginally buy down the experiential learning curve for any complex task, such as Defense Diplomacy. As a foreign element investing in the development and security of a nation and culture speak the native language. Even the most qualified representatives bring cultural biases, preconceptions, and misunderstandings of effects to the development of the strategic approach for U.S. engagement. More diplomatically experienced senior military officers can quickly leverage State and interagency expertise and effectively engage partner-nation leaders to bridge the perception gap and provide relevant guidance for a more effective and culturally nuanced strategic approach.

Furthering U.S. Security Objectives: Insights From BG Bailey

West Africa is a growing focus for USAFRICOM and a strategic challenge that leaders in Washington, DC, must pay more attention to. From democratic backsliding to increasing expansion of violent extremist organizations (VEOs) southward from the Sahel to general instability caused by the repercussions of climate change—particularly in the Gulf of Guinea—the West Africa security environment is degrading at a dangerous pace.

USAFRICOM shares its regional partners’ concerns regarding these security threats and pursues avenues that it can work toward to ensure mutual objectives in a synchronized and complementary manner are met. In my service as the deputy director for Strategy, Engagements, and Programs, I have been particularly struck by how much these aims can be furthered simply by listening and communicating with our partners in an open and frank manner that conveys our respect for the relationship. Open communication lays the foundation for future collaboration, while establishing trust between partners that can lead to unexpected yet welcomed outcomes. It is within this context that I relay my experience working with a partner in the Gulf of Guinea. I hope that in recounting it, readers can internalize the use of transparent dialogue in conjunction with the art of active listening to assist in furthering U.S. strategic security objectives.

I traveled to Guinea in October 2021 to meet with Guinean leaders to discuss growing the longer term security relationship between our two nations, especially looking at what USAFRICOM could do to support Guinean partners. During this visit, I had the honor of meeting with Guinea’s minister of defense. The original intent of the meeting was to share our respective views on the security situation within Guinea and the surrounding region—a dialogue that would help inform future security cooperation efforts. It was immediately apparent that the minister took my concerns seriously; at the same time, he waited patiently to steer the conversation in the direction of his choosing once I had made my points. The minister then touched on the historical root causes of regional instability in the Gulf of Guinea, ongoing contributing factors, and what he saw as possible solutions. By the end of the minister’s statement, I had received an in-depth analysis of regional instability that was more nuanced and sophisticated than I had ever received. The minister elucidated aspects of the security environment that had their roots in generational grievances that could not be mitigated with a single security cooperation initiative or even a strictly defense approach. An issue we viewed as strictly a security issue was suddenly framed in the broader context it warranted, and it became clear that to truly tackle the problem set, the command’s framing and approach to the issue would need a significant recalibration.

The minister and I ended the engagement conveying the importance we both placed on the relationship between the Guinean armed forces and USAFRICOM and promised to engage in the future on a deeper and more regular level. I returned to Stuttgart, Germany, with a deeper appreciation for the historical context of the security situation in contemporary Guinea and a message for our command’s leadership that our strategic approach to the country would need to change.

This dialogue led to a deeper understanding and appreciation for the Guinean perspective and fundamentally strengthened and changed the nature of the partner relationship—and furthermore helped to refine the priorities and approaches we are taking toward Guinea. USAFRICOM has begun engaging with the country in a more nuanced and, quite frankly, effective manner because of the lessons gleaned from an open and honest dialogue. While this single conversation will not be a panacea for the relationship, it could establish a better foundation to continue to strengthen the relationship as we work toward our mutual security objectives.

It was chance that the minister and I were able to have such an important and rich exchange, and with other individuals in our positions, it may have been different. However, by incorporating a baseline standard of Defense Diplomacy training into the career paths of our senior leaders—and specifically giving them the tools to engage in open communication and active listening when interacting with peers and senior leaders on the continent—we can work toward building stronger relationships and trust with our African partners.

Practicing Intelligence-Driven Defense Diplomacy: Insights From BG Keravuori

The degrading security situation in West Africa has been of significant concern for USAFRICOM and the broader U.S. Government due to the expansion of VEOs from the fragile states in the western Sahel recently affected by political instability and subsequent withdrawal of Western military forces.15 Political instability and economic decline exacerbated by environmental factors in the Sahel have enabled a gradual southward expansion of VEO activity over the last 2 years, threatening the Gulf of Guinea littoral countries of Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, and Togo.16 President Joe Biden’s 10-year implementation plan to prevent conflict and promote stability under the Global Fragility Act specifically “seek[s] to break the costly cycle of instability” in these countries, through an “integrated, whole-of-government approach” leveraging “new and existing diplomatic, defense, and development programs.”17

USAFRICOM prioritized strategic engagement with coastal West African partners and multinational organizations to understand growing security concerns and VEO threats through the unique lens of each country. By doing so, it became abundantly clear that the most effective approach to regional security is to support our African partner states in developing a coordinated strategy toward clearly defined and shared U.S. and African goals using the entire toolkit of statecraft and not solely defense.18

To achieve long-term regional security outcomes with this holistic approach, the U.S. military must suppress its inclination to quickly “solutionize” a problem with a purely defense approach.19 Alternatively, a simultaneous 3D interagency effort coordinated with European partners to layer effects could facilitate sustainable “clear and hold” efforts of African partners to reduce the threat and root causes of VEOs over time.20

Throughout the past few years, USAFRICOM and its interagency partners identified shared security priorities in Africa and formed the Combined Joint Interagency Coordination Group–West Africa (CJIACG-WA) in late 2022. The group’s focus is to coordinate the use of DOD intelligence-sharing and training capabilities with unique diplomatic and development investments of other U.S. Government agencies to support partner-led efforts to implement a holistic counter-VEO approach. The group effort, among many others, has come to fruition after years of building a common understanding, trust, and relationships among U.S. agencies.

Applying the 3D approach in Africa starts with building a unity of effort with State Department Country Teams and then bringing in DOD to synergize efforts and reduce friction caused by stovepiped communication and divergent priorities. Working in tandem with diplomatic missions with embedded defense attachés and USAID regional offices, senior-level engagements initiated discussions to address regional security challenges around worrisome trends, the effectiveness of the United Nations (UN) missions such as the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, or African-led organizations such as the Economic Community of West African States and the Accra Initiative. The unilateral and multilateral relationships built from consistent senior-level engagements are key to understanding how the United States can support African-led efforts and regional security initiatives with intelligence-sharing, security assistance, and operational support.

Conversations about security concerns and the metastasizing VEO issue with military and civilian leadership in coastal West Africa consistently become a broader examination of root causes of instability. Contributing factors such as governance, services, resources, desertification, corruption, human rights violations, porous borders, land-use governance, and a rapidly changing environment collectively contribute to instability and support VEO recruitment.21 As a starting point, a sustainable solution needs to address social, economic, diplomatic, and military challenges while encouraging collaboration among the military, government agencies, NGOs, and neighboring states.

Strategic engagements led by senior USAFRICOM leaders and staff to partner countries have spurred greater collaboration between their national civic and military leadership. The interagency representation of visiting U.S. delegations often encouraged attendance by counterparts representing internal security, foreign affairs, humanitarian aid, law enforcement, and legislative affairs. African partner militaries capitalized on the opportunity to coordinate interagency lines of effort with U.S. support, such as increasing investment in education, providing basic services to underserved areas, and mitigating secondary and tertiary effects of land-use legislation potentially causing conflict and displacement. Intelligence directorate–led engagements specifically reinforced the need for information-sharing agreements among agencies and neighboring states and the establishment of systems and processes for efficient information-sharing.

Consistent bilateral engagements with coastal West African partners shaped a crucial subsequent multilateral engagement at the command-hosted African chiefs of defense conference. This unique forum built consensus among regional partners on shared security challenges and the transnational problem of VEO activity. USAFRICOM was trusted as a helpful partner to facilitate a multilateral discussion between coastal West African partners, which was particularly challenging due to the lack of a common language, cross-communication platform, or shared security framework involving the United States. Ultimately, these bilateral and multilateral engagements with coastal West African partners informed the purpose and establishment of CJIACG-WA by a trusted partner to address enduring security challenges in West Africa. Additionally, it contributed to encouraging African partners to “embrace joint, interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational mindsets,” something that is happening across combatant commands.22

Professionalizing the Purple to Gold Pipeline: Insights from BG Keravuori

My assignment as USAFRICOM’s deputy director of intelligence was an example of successful joint force talent management considering the confluence of language proficiency, education, and interagency experience that allowed me to engage with senior African and European civil and military leaders on shared security interests. Serving in command and directing a commander’s action group hit my major key development milestones as an Army officer, but it was the broadening and interagency assignments that best prepared me to conduct Defense Diplomacy in Africa.

As French is the lingua franca in West Africa, my fluency in the language enabled more direct and candid discussions with senior African civil and military leaders and the French Armed Forces. The close partnership with France in Africa is made more striking through personal relationships and shared interests. Recently serving as a U.S. liaison to a French Army division and institutional exposure to the French military academy in Saint-Cyr provided me with a practical understanding of French defense strategy, foreign policy, and security efforts in the Sahel. The French military’s long history of security efforts in West Africa provides crucial context and insight, and its continued 3D efforts often align with USAFRICOM priorities. Such experiences and relationships prove indispensable to deepening our close partnership with the French Armed Forces in West Africa.

Defense Diplomacy in practice was particularly well-served by my formative experiences as a foreign area officer (FAO), during which I was exposed to the nuances of diplomatic language and culture and the bureaucratic challenges of security assistance. Continued involvement with the FAO community also enables an advantageous link to the defense attaché offices and Country Teams at U.S. Embassies across the continent. An interagency broadening assignment as a FAO at the Department of State provided familiarity with subdepartment level stakeholders and processes that now enable flat communications between USAFRICOM and State for a cohesive U.S. response promoting unity of effort with African partners.

Going Beyond Familiarization

Members of the U.S. joint force often assume significant responsibility for promoting U.S. foreign policy abroad from junior to senior officer levels through partner engagements, security forums, combined exercises, and multinational operations. Preparing military leaders with a foundational understanding of the interagency community is fundamental to integrating efforts across the 3Ds and promotes more immediate integration with partner efforts on common interests to achieve sustained results at a modest, shared cost.

Based on the reflections of Defense Diplomacy practitioners, the joint force is best prepared through formal education and interagency experience. Having institutionalized the concept, training, and experiences to achieve joint integration, it is time for the joint force to likewise institutionalize the same for interagency integration. As famously stated by Carl von Clausewitz in On War, “war is not merely a political act but a real political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse, a carrying out of the same by other means.”23 Military officers, through campaigning in peacetime or conflict during wartime, participate in political dialogue. The military has long known the value of training and experience to achieving success, investing hundreds of thousands of dollars into training each Servicemember, building training and experience at each rank.

The same cannot be said for interagency training, where only a small subset in specialty fields receive any experience and training beyond a PowerPoint overview. Professionalizing interagency training and experience to build a bench of 3D officers at field grade ranks and above level can potentially magnify the effects of national security investments in the same way the joint force integration created an advantage over Service-centric militaries.

Gold Gilding the Purple Joint Force

Military leadership during the reforms of the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 was adamantly against the proposed changes, and joint opportunities were seen as career-ending assignments.24 With nearly 40 years of hindsight, the jointness enabled by Goldwater-Nichols is now one of the core strengths of the U.S. military.25 Services will inevitably be reluctant to weigh interagency experience in career advancement due to institutional pressure, but DOD can shift institutional Service culture to value interagency experience just as it has for joint experience through policy change and evaluation. The U.S. military enjoys an advantage over its adversaries by being able to effectively execute joint operations, and interoperability is the next phase of preparation for military leadership to overcome complex modern security challenges.26

The joint force prioritizes joint experience as a requirement for senior military leaders through joint qualification accreditation but currently has no formal requirement or incentive for interagency experience, the importance of which has been repeatedly discussed and advocated for in professional journals over the last two decades. The introduction of an interagency qualification requirement for career advancement would expand acculturation across development, diplomacy, and defense agencies. Elevating the importance of interagency assignments with drivers of U.S. domestic and foreign policy through military broadening assignments at USAID and the Departments of State, Commerce, Treasury, and Energy would reduce the seams in U.S. whole-of-government strategy, policy, and efforts.

Expanding interagency assignments and introducing competitive interagency credit would require refocusing existing resources and add costs for permanent change-of-station moves. To bring costs down, joint credit could be reduced to 2 years to facilitate 1 year of interagency credit, an approach that could allow personnel assigned to joint billets—especially within the National Capital Region—to rotate through 1-year interagency assignments with minimal resource requirements, avoiding the costs and turbulence of a permanent move.

While not everyone serving in joint assignments would be able to achieve interagency credit using this model, the joint force overall would have a significantly expanded bench of midgrade and senior officers with interagency acculturation and experiences enabling greater 3D integration and more effective Defense Diplomacy efforts in the future.

As Norman Schwarzkopf told a group of Naval Academy graduates in 1991, “the more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war.” Nowhere is there a lower cost opportunity to increase training to achieve strategic-level effects than advancing from a joint to an interagency force.

About the authors: Brigadier General Rose P. Keravuori, USA, is Director of Intelligence, J2, at U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM). Brigadier General Peter G. Bailey, USAF, is Deputy Director, Strategy, Engagement, and Programs, J5, at USAFRICOM. Lieutenant Colonel Eric A. Swett, USA, is Chief, USAFRICOM J25 Plans West. Captain William P. Duval, USA, is a Reserve Officer supporting the Intelligence Directorate at USAFRICOM.

Source: This article was published in Joint Force Quarterly 111, which is published by the National Defense University.

Notes

1 B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy (New York: Praeger, 1954).

2 Lawrence Kapp, General and Flag Officers in the U.S. Armed Forces: Background and Considerations for Congress, R44389 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, February 1, 2019), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44389/7.

3 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 3500.02C, Universal Joint Task List Program (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, December 19, 2022), https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/training/cjcsi_3500_02c.pdf?ver=DcbU-aEXlhWsm-03av9h4A%3d%3d.

4 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010, Pub. L. 111–84, 111th Cong., 1st sess., October 28, 2009, https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ84/PLAW-111publ84.pdf.

5 International Defence Engagement Strategy (London: Ministry of Defence, 2013), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/international-defence-engagement-strategy.

6 Dan Lamothe, “Retired Generals Cite Past Comments from Mattis While Opposing Trump’s Proposed Foreign Aid Cuts,” Washington Post, February 27, 2017.

7 James Mattis and Stephen Hadley, “Secretary Mattis Remarks on the National Defense Strategy in Conversation with the United States Institute [of] Peace,” Department of Defense, October 30, 2018, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/1678512/secretary-mattis-remarks-on-the-national-defense-strategy-in-conversation-with/.

8 M. Wade Markel et al., Developing U.S. Army Officers’ Capabilities for Joint, Interagency, Intergovernmental, and Multinational Environments (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2011), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9631.html.

9 Kyle J. Wolfley, “Military Power Reimagined: The Rise and Future of Shaping,” Joint Force Quarterly 102 (3rd Quarter 2021), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2679810/military-power-reimagined-the-rise-and-future-of-shaping/.

10 Hans Binnendijk et al., Affordable Defense Capabilities for Future NATO Missions (Washington, DC: Center for Technology and National Security Policy, February 23, 2010), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/occasional/CTNSP/NATO_Affordable-Defense-Capabilities.pdf?ver=2017-06-16-142145-460.

11 “About the Command,” United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM), https://www.africom.mil/about-the-command.

12 The U.S. Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability: 10-Year Strategic Plan for Coastal West Africa, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, and Togo (Washington, DC: Department of State, March 24, 2023), https://www.state.gov/the-u-s-strategy-to-prevent-conflict-and-promote-stability-10-year-strategic-plan-for-coastal-west-africa/; U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa (Washington, DC: The White House, August 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/U.S.-Strategy-Toward-Sub-Saharan-Africa-FINAL.pdf.

13 United States Africa Command: The First Ten Years (Stuttgart: USAFRICOM, 2018), https://www.africom.mil/document/31457/united-states-africa-command-the-first-ten-years.

14 Ryan McCannell, “At The Nexus of Diplomacy, Development, and Defense—AFRICOM at 10 Years (Part 3),” War Room, September 29, 2017, https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/special-series/anniversaries/forming-africom-part-3/.

15 Center for Preventative Action, “Violent Extremism in the Sahel,” Council on Foreign Relations, Global Conflict Tracker, August 1, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel.

16 Leif Brottem, “The Growing Threat of Violent Extremism in Coastal West Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 15, 2022, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/the-growing-threat-of-violent-extremism-in-coastal-west-africa.

17 President Biden Submits to Congress 10-Year Plans to Implement the U.S. Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability (Washington, DC: The White House, March 24, 2023), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/24/fact-sheet-president-biden-submits-to-congress-10-year-plans-to-implement-the-u-s-strategy-to-prevent-conflict-and-promote-stability.

18 William J. Burns, Michèle Flournoy, and Nancy Lindborg, U.S. Leadership and the Challenge of State Fragility, Fragility Study Group Report (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, September 2016), https://www.usip.org/publications/2016/09/us-leadership-and-challenge-state-fragility.

19 Brian Dodwell, “A View From the CT Foxhole: Brigadier General Rose Keravuori, Deputy Director of Intelligence, United States Africa Command,” CTC Sentinel 16, no. 1 (January 2023), https://ctc.westpoint.edu/a-view-from-the-ct-foxhole-brigadier-general-rose-keravuori-deputy-director-of-intelligence-united-states-africa-command/.

20 Aneliese Bernard, “Jihadism Is Spreading to the Gulf of Guinea Littoral States, and a New Approach to Countering It Is Needed,” Modern War Institute, September 9, 2021, https://mwi.usma.edu/jihadism-is-spreading-to-the-gulf-of-guinea-littoral-states-and-a-new-approach-to-countering-it-is-needed.

21 “Violent Extremism in the Sahel.”

22 Kurt W. Tidd and Tyler W. Morton, “U.S. Southern Command: Evolving to Meet 21st-Century Challenges,” Joint Force Quarterly 86 (3rd Quarter 2017), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1219106/us-southern-command-evolving-to-meet-21st-century-challenges/.

23 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. J.J. Graham (Ware, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 1997).

24 James R. Locher III, “Has It Worked? The Goldwater-Nichols Reorganization Act,” Naval War College Review 54, no. 4 (Autumn 2001), 104, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2537&context=nwc-review.

25 Charles Davis and Kristian E. Smith, “The Psychology of Jointness,” Joint Force Quarterly 98 (3rd Quarter 2020), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2340620/the-psychology-of-jointness.

26 Dan Sukman and Charles Davis, “Divided We Fall: How the U.S. Force Is Losing Its Joint Advantage Over China and Russia,” Military Review, March–April 2020, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/March-April-2020/Sukman-Divided.