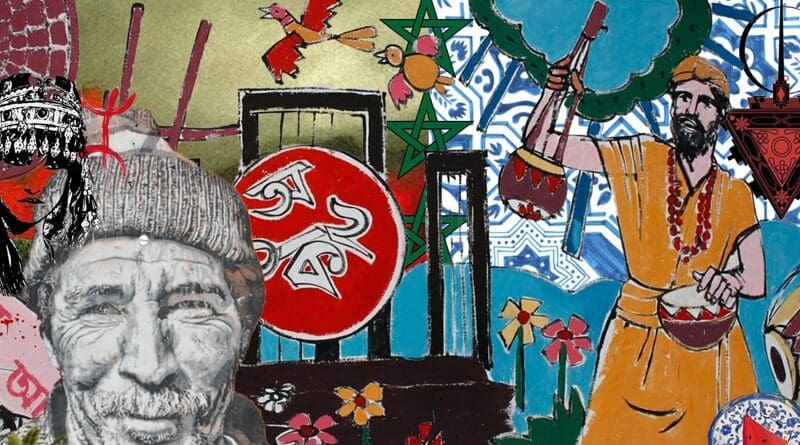

Embracing The Soul Of Identity: International Mother Language Day – OpEd

By Sneha Khan

As I sit to write these words on the significance of International Mother Language Day, I am filled with emotions that run deep within me. For me, today is not simply any other day of observance, but a day that represents the very essence of my being; the culmination of blood, sweat, tears, strength, and resilience that allowed for the continuation of my bloodline, and thus my bringing into existence.

As a Bangladeshi, today I find myself reminded of the profound power of language as I think about my people’s boundless, eternal love for our rich linguistic heritage, as well as the struggles of my ancestors to preserve it no matter the cost. After all, the language we speak isn’t merely a means of communication; our languages hold intricate memories and information for thousands of years of our cultures.

The genesis of International Mother Language Day traces back to the tumultuous period of the Bangladesh Liberation War and the Bengali Language Movement. When Pakistan was formed in 1947 after the British partition of the Indian subcontinent, it was composed of two geographically

separate regions: East Pakistan (now known as Bangladesh) and West Pakistan (now known as Pakistan). The two parts differed significantly in terms of culture and language, and were also geographically separated by the entire nation of India.

In 1948, the Pakistani government mandated Urdu as the sole national language, as well as the replacement of Bengali script with Arabic or Roman script. Sparking widespread protests among the Bangla-speaking majority, it was a time when my people fought tirelessly to resist the oppressive forces that sought the complete erasure of our unique language and identity.

The movement came to a climax during the tragic events of February 21, 1952, when university students and other political activists boldly challenged the law by organizing a protest, to which police officers responded by fatally shooting demonstrators, leading to mass civil unrest in the aftermath. The brave souls who sacrificed their lives for the right to speak their mother tongue ignited a flame that continues to burn brightly, illuminating the path for linguistic diversity and cultural pride worldwide.

Languages are the most powerful instruments of preserving and developing our tangible and intangible heritage. All moves to promote the dissemination of mother tongues will serve not only to encourage linguistic diversity and multilingual education but also to develop fuller awareness of linguistic and cultural traditions throughout the world and to inspire solidarity based on understanding, tolerance and dialogue. — United Nations

The initial idea to celebrate International Mother Language Day was the initiative of Bangladesh, first announced as a worldwide annual observance by UNESCO in 1999, and formally recognized by the United Nations General Assembly in 2002 as part of efforts to safeguard all languages worldwide.

For me, the implication of this day transcends mere historical remembrance; it’s deeply personal. My own family’s history is intertwined with the adversities of that era. My great-grandfather, who worked as a hospital doctor, was martyred as a part of the genocidal campaign targeting social and cultural institutions such as healthcare facilities, as well as the systematic execution of the nation’s intellectuals. My grandfather was inspired to become a freedom fighter who fought valiantly in the Liberation War, enduring unimaginable hardships including several bullet wounds to the body. My grandmother gave birth to my father in a refugee camp, unsure whether she would have to raise her son alone, or if they would even survive having such scarce food resources.

I exist now only because my bloodline withstood years of ethnic cleansing, genocide, and famine. I am living a testament to the fact that my people, and thus our language and culture, endured. The narratives of my direct family, etched in the chronicles of our family lore, serve as a constant reminder of the price paid for the freedom to speak our mother tongue.

As a Bangladeshi, my connection to my country, culture, and language is unwavering. It’s a bond that transcends geographical boundaries and spans generations. The language we speak is the very soul of our identity, carrying within it the collective stories, dreams, and aspirations of our people.

But the resonance of International Mother Language Day extends far beyond the borders of Bangladesh. Here in Morocco, a nation rich in cultural diversity and heritage, I have been so fortunate as to witness a very special, continuously growing movement. In recent years, there has been a big push by activists to advocate for the indigenous Amazigh community’s rights and alleviate the threat they have experienced in regard to the loss of their language, culture, and therefore, identity. This fight against marginalization has been known as the Amazigh Cultural Movement(ACM).

The Amazigh, or the Free Men, are an indigenous civilization originating in North Africa whose existence dates back more than 20 000 years. Long struggling for cultural acknowledgment due to factors such as invasion and colonization, activists among the Amazigh community have persistently fought against repressive policies while advocating for measures to preserve the identity. At the heart of historical and contemporary Amazigh renaissance movements lie the principles of Awal (language), Akkal (land), and Ddam (blood).

The Amazigh language, called Tamazight, is an Afro-Asiatic language composed of many dialects. In Morocco, these dialects include Tachelhit spoken in the South, Tamazight in central Morocco, and Tarifit in the North. While Arab colonization beginning in the 7th century gradually supplanted these indigenous languages, it was during the French conquest of North Africa, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that the suppression and erasure of the Amazigh language reached its zenith.

The French colonial administration implemented policies aimed at assimilating the indigenous population, with the country’s educational system structurally favouring Arab and French culture over Amazigh traditions. The imposition of French as the primary language of administration and commerce relegated Amazigh languages to oral traditions and informal settings.

French colonizers actively discouraged the use of Amazigh languages and sought to dismantle traditional Amazigh institutions and practices. This systematic campaign of linguistic suppression aimed to homogenize the diverse populations of North Africa under French colonial rule.

After centuries of Amazigh communities and grassroots activists struggling in their quest to gain appropriate national status, in 2011, following the Arab Spring, a new constitution was ratified in Morocco. Article 5 of this constitution designates Tamazight as an official language of Morocco, with Neo-Tifinagh chosen as the script. Consequently, most road signs and official buildings now feature bilingual displays.

The ACM, drawing similarities to the Bengali Language Movement as well as many other resistance movements worldwide, seeks to revive and celebrate the historically suppressed indigenous languages and traditions of the Amazigh people. It’s a testament to the enduring spirit of linguistic and cultural pride that reverberates across continents.

In Morocco, the current Tamazight-speaking population totals around 15 million people. As I speak to Moroccans here about their indigeneity, I can see their eyes light up at the simple mention of the word “Amazigh”. In our conversations, I hear passionate stories about land, art, food, clothing, music, and spirituality, that were passed down from generation to generation. And I am reminded that the Amazigh people are very much alive, and so is their beautiful, intricate culture.

All across the world, the language rights of minority groups are intertwined with their claim for recognition within society. Their demands bolster the nation’s plurality across linguistic, cultural, religious, ethnic, and political dimensions. On this International Mother Language Day, let us reaffirm our commitment to preserving and celebrating the languages that define us. Let us honor the sacrifices of those before us and pave the way for a future where we no longer tolerate linguicide and culturicide, and watch as mere bystanders to the destruction of such special human systems.

As I reflect on such a sorrowful day as today, I am but filled with hope for the future. I have hope for a world where every language is cherished, and where cultural diversity is embraced as a source of strength rather than division. I hope for the continuation and longevity of Amazigh languages across Morocco, ensuring that future children continue to inherit this wonderful linguistic heritage. And most importantly, I hope for more power to every oppressed person across the world, because as long as we continue to exist and resist, our mother tongues will never succumb.