Small Island States Matter In Great Maritime Game – Analysis

The India-Maldives fracas highlights how shifts in small coastal states can have impact in a burgeoning maritime great game. The seething rivalry between regional powers gives smaller countries a chance to renegotiate ties with their bigger neighbors. It creates spaces to grow their autonomy and expand their diplomatic horizons. The rise of new partners allows them to reimagine their position in a brewing geopolitical competition, leveraging their strategic location to exact as many concessions from the contenders as possible. Not wanting to be reduced to mere pieces on a chessboard, they are exerting more agency to navigate increasingly uncharted waters. Domestically, the great power gulf also allows politicians to project their “independent” and “nationalist” credentials to win votes or defend a chosen foreign policy.

As the world’s largest trading nation, China has a deep interest in securing vital passageways for its energy and commerce. It has developed a bluewater navy – the world’s largest by fleet size – and has naturally sought access to countries astride vital sea lanes. Whether through infrastructure, investments, tourism, trade, or capacity building, Beijing offers lucrative incentives to gain ground. In turn, its growing footprint in the Indo-Pacific is increasing the concerns of mainstay regional powers. Contest for access – either to get an anchor or to frustrate it, depending on where one sits – has become a key feature of great power competition, which highlights several notable points.

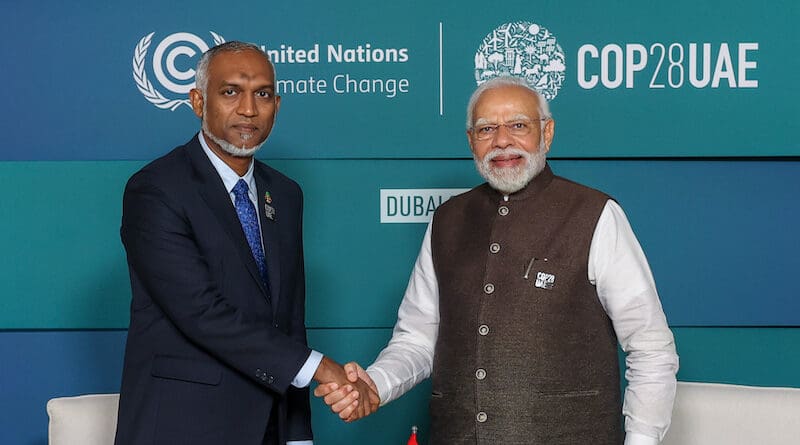

First, small states can have a large impact. The Maldives has a land area of less than 300 square kilometers, but its maritime domain covers 90,000 square kilometers. Over 99% of the country’s territory is water. The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) has a land area of only 700 square kilometers but is spread out over 2.6 million square kilometers of the Pacific. These low-lying atoll states provide an arena for major power contests, a boon for the islanders if their leaders can play it right. New Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu won his position on a platform of “India Out,” calling for an end to Indian military presence, arguing it compromises his country’s sovereignty. He even broke tradition by not making Delhi his first diplomatic stop while in office, choosing Ankara instead, after which he flew to Dubai and Beijing. It is a big splash for the tiny nation of 500,000.

FSM is the only country with a Compact of Free Association (COFA) with the U.S. that established official relations with Beijing. The other two – Palau and the Marshall Islands – maintain diplomatic ties with Taipei. All three Central Pacific states renewed their COFA with Washington last year, granting another 20-year exclusive military access in exchange for generous funding. But the islands’ leaders warn that delays in U.S. Congressional approval of the agreement could open doors for other suitors, including China. Beijing just flipped Nauru two days after elections in Taiwan. In 2022, it concluded a security deal with the Solomons that may portend possible naval access. Expectedly, China will continue to probe opportunities to expand its influence and strategic foothold in this blue continent.

The attention these island nations are receiving is unprecedented, as they’re becoming the frontlines for rival powers to jostle for geostrategic positioning. Additionally, the Covid-19 pandemic did not stop China from opening new embassies in the Solomon Islands and Kiribati in 2020. Last year, to play catch up with China, the U.S. reopened its embassies in the Solomons and Seychelles after a 30-year and 27-year hiatus, respectively. It also expanded its diplomatic facility in Mauritius and established embassies in Maldives and Tonga, with plans to set up missions in Cook Islands, Niue, and Vanuatu. It is up to remote Indo-Pacific island states to translate this newfound interest from able suitors to economic windfall or firmer climate change commitments from industrial economies. Public pulse and leadership change in these tropical archipelagoes become worth following as they may determine where the foreign policy compass will point next.

Second, relations between traditional resident powers and their smaller neighbors can no longer be business as usual. Actors wanting to win smaller neighbors’ favor must be more attentive to their needs and not be complacent with their privileged position as longstanding donors or partners. Underwhelming or unrealized pledges are a factor behind shifting allegiances among small outlying islands facing existential threats from rising sea levels. Foreign policy oscillations in smaller countries should not be simply or condescendingly dismissed as mere products of corruption, elite capture, or some elaborate information operation. Labels like pro-India, pro-China, or pro-U.S. or their antithesis are overly simplistic, and give too much credit to big powers, deny agency to smaller states, and fail to account for the changing sociopolitical ferment and growing aspirations of peoples from smaller nations. The transformation from “India First” to “India Out” was neither instant nor the whim of just one politician. And “India Out” might not necessarily mean “China In.” For example, the Maldives is reaching out to Turkey and affluent Gulf countries. Providing access to more than one party – instead of an exclusionary one – is also not an unheard-of scenario, as Djibouti gave military access to the U.S., France, Italy, China, Japan and Saudi Arabia.

However, it may take a leap of faith for small island states long reliant on a major patron to seize the moment., as theory of offending a big neighbor may weigh heavy on them.

One silver lining from the increasingly turbulent geopolitical seascape is that small island states now drive harder bargains. They have a greater appreciation of their worth, understand that rival powers may not have their best interests in mind and know that only they can chart their future. Waves come and go leaving the sand to contend with the elements.

This article was published at China-US Focus