When Romania Flirted With A Fate Like Yugoslavia’s – Analysis

Thirty years since Romania’s Black March violence, BIRN reconstructs the events that would shape post-communist relations between Romanians and the country’s Hungarian minority for years to come.

By Marcel Gascón Barberá

Thirty years ago, a matter of months after a popular uprising forced the army to topple the communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu, Romania returned to the international spotlight, but the circumstances were very different.

The December 1989 uprising against Ceausescu saw hundreds of thousands of Romanians of all ethnic origins risk their lives to bring down a repressive regime.

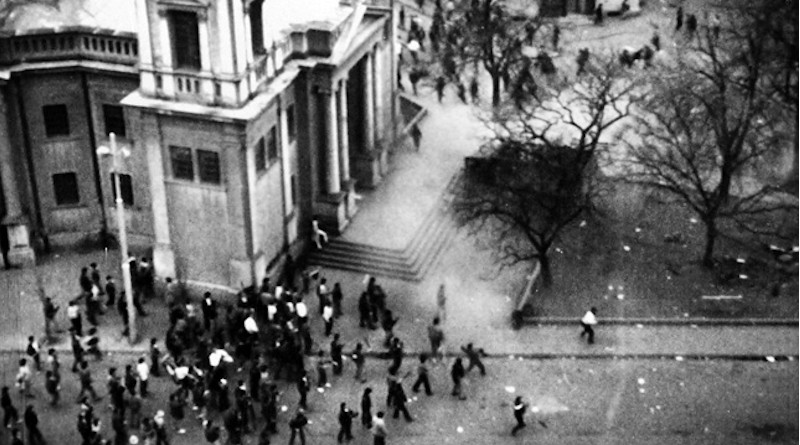

But events took an ugly turn between March 19 and 21, 1990, as mobs of Romanians and Hungarians in the Transylvanian town of Targu Mures fought each other to the death.

Events marking three decades since one of the darkest chapters of Romania’s transition from communism have been cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic convulsing the globe.

But BIRN has spoken to some of those directly or indirectly involved in what is known in Romania as Black March, in an effort to reconstruct what went on and ponder the chapter’s impact on the development of Romanian democracy.

The facts

The end of 24 years of nationalist-tinged hardline communism threw up considerable challenges for Romania, not least the question of national minorities and in particular that of 1.5 million Hungarians against whom the old regime’s chauvinist narrative was ostensibly built.

The advent of democracy was seen by Hungarians in Romania as an opportunity to gain a level of self-governance and education in their own language. Such a prospect, however, caused alarm in Romanian political and cultural circles at the time.

Concessions regarding collective rights were denounced as potentially opening the door for Hungary to reclaim some degree of influence and control over Transylvania, home to the overwhelming majority of Romanian Hungarians. Hungary lost the region in World War One, a cause of much resentment in the country even today.

Ethnic Hungarians, who at the time constituted more than 60 per cent of the population of Targu Mures, moved quickly to demand a separate Hungarian-language education curriculum, but were strongly opposed by Romanians who said it would be segregationist.

Tensions grew as the Hungarian management of the local high school barred Romanian pupils from entering in a bid to speed up the institution of Hungarian as the language of instruction.

Later, on March 16, as part of a campaign of incitement driven by public and pro-government media, the state press agency falsely reported that a local pharmacy had stopped serving Romanian customers. It was printed by the pro-government national press and triggered a violent mob attack on the pharmacy, a rehearsal of what was about to follow.

On March 19, a crowd of Romanians armed with stones and crowbars attacked the Targu Mures headquarters of the UDMR party, the main ethnic Hungarian political party. Hungarians in the square in front of the town hall were also attacked, before pitched battles erupted until the army deployed late on March 20 and dispersed the crowds. Five people died and some 300 were injured.

Who lit the fuse?

Most observers and those in office at the time suspect hidden forces behind the riots, but disagree on the identity.

In March 1990, Petre Roman was prime minister at the head of a provisional government installed after the December revolution under the name of the Provisional Council of National Union, CPUN.

In line with his government’s official position back then, Roman told BIRN that “Hungarian revisionist circles not from Hungary but from the US” played a major role in instigating the violence, with the aim of triggering a conflict of international scale or what he called “a Bosnia-type scenario”.

“In other words, to push towards a protectorate zone under the UN, which practically would have meant the disintegration of the Romanian state,” Roman said in an interview by phone.

To support the claim, Roman cited the alleged influence of Hungarian émigrés looking to profit from post-communist Romania’s weakness and return Transylvania to Hungary’s control. He cited the presence of an Irish television crew in the town when the clashes broke out as evidence of a pre-planned plot, supported again by the fact the crew wrongly identified as Hungarian a Romanian man filmed being badly beaten in a video that encapsulated the violent events.

Kincses Elod, CPUN vice-president in the Targu Mures area, disagrees. Elod found himself at the centre of events as Romanian demonstrators called for his resignation before attacking the UDMR headquarters.

In his view, Romania’s former communist police leaders conspired with CPUN leaders in Bucharest to create a threat to national security in order to justify their reinstatement in a new post-communist intelligence service.

Three months of paid leave granted by Romania’s new authorities to the bulk of former Securitate [communist political police] cadres was due to finish at the end of March, Kincses noted in an interview with BIRN, after which they would have to look for new employment.

According to Kincses, the still influential Securitate – part of which had already been absorbed into the new administration – desperately needed to “change the hostile atmosphere” that surrounded them in Romanian society.

Kincses alleged that, in fuelling tensions in Transylvania via the media and promoting Romanian chauvinist groups such as the cultural association Vatra Romaneasca, the Securitate officers and their protectors in the provisional government provoked the clashes in Targu Mures in order to drum up support for the urgent establishment of a new secret service, something many Romanians vehemently opposed after the abuses they suffered at the hands of the Securitate.

The former politician recalled how a statue in the town of Romanian national hero Avram Iancu was defaced with graffiti in Hungarian, an incident widely reported on by Romanian media. The graffiti, Kincses said, contained “two mistakes in two words” and “was clearly written by someone who did not speak Hungarian”.

Former CPUN member and anti-communist dissident Gabriel Andreescu said the new Romanian Intelligence Service, SRI, which absorbed the Securitate cadres facing unemployment, was created on March 26, 1990, just days after the Targu Mures violence, via an opaque procedure that bypassed CPUN legislative body of which he was part.

Deliberate delayed reaction?

Andreescu told BIRN that villagers from near Targu Mures were armed and bussed into the town “to defend their fellow Romanians”, further evidence, he said, of the organised nature of the anti-Hungarian violence.

He also accused his CPUN superiors at the time of deliberately delaying the response to the violence, a claim supported by Kincses but strongly denied by former prime minister Roman.

“I asked [president Ion] Iliescu to intervene, I asked Petre Roman,” Kincses told BIRN.

Asked about the allegation his government sat on its hands, Roman replied: “This is completely false.”

He did say he believed some former Securitate agents may have been involved in whipping up the violence, but cautioned against downplaying the element of spontaneity.

“There were extremists [in both camps], and we should not forget that extremist people act as extremists,” Roman said to BIRN.

What does the Securitate say?

Retired SRI General Virgil Magureanu was among the former Securitate officers brought into the new, post-communist intelligence service and, through his books and writing for the SRI veterans’ magazine, is widely seen as an unofficial spokesman for the former Securitate.

In The Defense of the Constitutional Order (2016), Magureanu rejects the alleged connection between Black March and the creation of the SRI. “The creation of the SRI only a few days after the bloody Targu Mures events … has induced an artificial link between the two moments,” he wrote.

Instead, he wrote, the clashes were triggered by the radicalisation of Hungarians in Romania supported by “the insistent actions of revisionist Hungarian groups in Hungary and the diaspora” to generate, with the support of “some Western leaders”, “an inter-ethnic conflict in Transylvania with the goal of placing this province under international arbitration”.

Kincses is dismissive of such theories.

“The Securitate officers, then and now within the SRI, make a very good living fighting against so-called Hungarian irredentism,” he said.

“If [the irredentist threat] disappears, how could they justify the exorbitant income they make claiming victory after victory over an enemy that doesn’t exist?”

Might Romania have suffered a similar fate to Yugoslavia?

Many observers have compared the climate in early 1990 in Transylvania with that of the ethnic hatred building towards conflict in federal Yugoslavia.

The fact Romania escaped such a fate can be explained in large part by the demographic composition of Transylvania, said Andreescu, who since his release from detention as a political prisoner in 1989 has studied and written extensively on minority rights.

Almost eight million Romanians living in the region in the early 1990s constituted a solid majority, he said, so it was not conceivable that Hungarians could break away as, say, Kosovo’s ethnic Albanian majority did from Serbia in 1998-99 in the final chapter of Yugoslavia’s bloody demise.

On the other hand, he said, nationalist movements at work in Transylvania failed to rally sufficient support among the cultural elite and civil society. A substantial part of Romania’s intellectual, civic institutions and opposition parties refused to take the bait of chauvinism, making a wider conflict more unlikely.

This is not to say that Black March did not leave its mark on Romanian democracy. The Romanian National Unity Party, PUNR, which emerged from Vatra Romaneasca, dominated the Transylvanian political scene for years to come with an aggressively nationalist and anti-Hungarian discourse.

In the opinion of Kincses, the Targu Mures events marked the end of the “love story” between Romanians and Hungarians that began in Timisoara in mid-December 1989 when Romanians of all origins took to the streets, shrugging off fears of the Securitate, in support of a persecuted ethnic Hungarian pastor.

It was the beginning of the end for Ceausescu.