Travails Of Kohinoor: A Journey Through Time And Empires – Analysis

The Kohinoor Diamond is a journey through time and empires. From its humble origins in ancient India to its current home in the British crown, the diamond has been shaped by the events of history and has played a role in the rise and fall of various empires. Despite the legends and myths that surround it, the Kohinoor remains a symbol of wealth, power, and prestige, and its journey through time is a testament to its enduring legacy.

The largest diamond mines are found in South Africa, where they were discovered in 1700 CE. Before this discovery, India was the only supplier of diamonds in the world. All the ancient lores of India – Veda, Purana, the epics, other legends and folklore – speak of diamonds, its characteristics, and stories around them. In contrast, Europe learnt of diamonds and its value only in the late 1600s. One of the earliest evidence of the importance given to diamonds and their mining in India can be gathered from the Arthashastra, a treatise on governance, administration, law, politics, strategy, and defence. The Arthashastra was authored by one of India’s renowned statesmen of the 4th century BCE, popularly known as Kautilya and Chanakya. Diamonds find a specific mention among this list as a precious commodity for trade, treasury, savings, and adornment in the 4th century BCE itself. The Arthashastra was produced around 336 BCE, the same time when Alexander, the Macedonian had invaded and retreated from the North Western parts of India.

Most of the legendary diamonds of today were mined in India and owned by different kings and temples of India till the 1700s. Marco Polo, the Italian adventurer who visited India in 1295 CE, documenting what he saw and learned during his visit to India. He writes, “The bigger diamond stones went to the various Indian kings and the great Khan. The smaller and refused stones were sent to Europe from the port of Guntur District.”

Diamonds also made their way to other ancient civilizations, going by the records of the Greek. Incidentally, the word diamond has its roots in the Greek word, adamas ‘indestructible’. Pliny in his work Naturalis Historiae, in 77 CE records, wrote, “Most large precious stones are of Indian origin.” Pliny calls them Adamas from India.

Diamond mining in India along the Adamas River was mentioned by Ptolemy in 140 CE. The Greeks referred to the Krishna river in South India as the Adamas river. A 300-km-stretch along this river has been the scene of intense diamond mining activity since millennia. It was only much later, during the colonization of India, that most of these big diamonds were prized away to Europe and America. Truly, the Golconda diamond history is a long and fascinating one.

Golconda mines in Andhra Pradesh were known for its brilliant diamonds that were coveted all over the world. Besides the famous Kohinoor diamond, the illustrious Golconda diamond history includes others like Hope and Regent. The Golconda diamonds stood apart for their size and crystal clarity. Most diamonds have traces of nitrogen in them which gives them a yellowish tinge and they are called Type I. The Golconda diamonds were called Type 2. Even in this category, they were classified as Type 2a, as they did not have any nitrogen, considered to be an impurity in diamond. Even those with some tinge of pink or blue or gray, were classified as Type 2b as they got their color from elements such as Boron.

But how were diamonds introduced in Europe? In the year 1650 CE, the French traveller and jeweller Jean Baptiste Tavernier, who came to India about six times, visited the mines of Golconda to procure diamonds. These he sold them to the royals and aristocrats of Europe. He introduced them at the court of King Louis XIV of France in 1669. He made a diamond bracelet, bazuband, worn in the upper part of the arm, for King Louis XIV, who spent an equivalent of $75 million in those days for the diamonds procured from India.

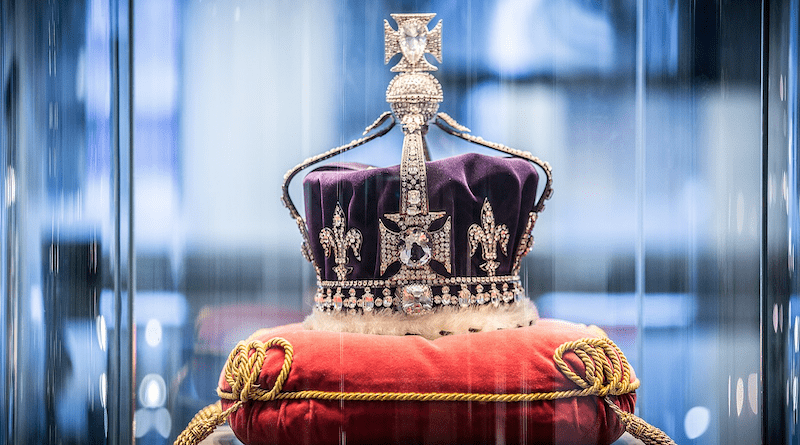

Named for its colossal size, the stone was originally 186 carats, and the size and heft of a hen’s egg. With a worth of at least €140 million, the Kohinoor diamond is of inestimable value; this gorgeous diamond is housed in the Tower of London, but is a point of contention, with the Governments of India, Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan claiming ownership of it since India’s independence from the UK in 1947. The Kohinoor diamond is one of the most important diamonds in the world and forms part of the United Kingdom’s Crown Jewels. The 186 carat super Kohinoor diamond was found in India, but fell into Queen Victoria’s hands. She in turn had it cut into a stunning 109 carat brilliant. The Kohinoor diamond has only been worn by queens and is currently set in Queen Elizabeth’s crown. It can be admired at the Tower of London.

Of all the diamonds in the world, the story of the Kohinoor diamond is by far the most famous. A Golconda classified diamond, whose origins are lost in the midst of time, Kohinoor today occupies the pride of place on the British crown, tucked away in the Tower of London. This prized diamond in her long history has travelled all over the world and been possessed by many rulers. She is known to have travelled back and forth within India and between India, Persia, and Afghanistan – changing hands from one ruler to another. However in all this journey, Kohinoor was never bought or sold but changed hands only due to inheritance or as a token of gift or due to extortion, looting, trickery and treachery. In fact, it was only after reaching Nadir Shah of Persia, who gave her the Persian name Kohinoor meaning “Mountain of Light”

The Origin of Diamond

Golconda diamond history says that trade flourished during the time of the Kakatiya dynasty, who established the famous Golconda fort in 975 CE. Diamonds were mined from the region in and around Golconda, then cut and traded from there. The fortress city of Golconda was the market city for diamond trade and gems sold there came to be called Golcondas. Golconda became synonymous with diamonds for Europe.

By the 1880s, the Golconda diamonds had gained so much popularity for their size, weight, and quality that they became a coveted brand of diamonds. The word ‘Golconda’ became synonymous for best quality diamonds. Soon, Golconda became a generic term to denote a rich mine or source of immense wealth too. The Golcondas also earned immense wealth for India.

The origins of the diamond, as well as its many connotations, lies in India where it was first mined. The word most generally used for diamond in Sanskrit is transliterated as vajra, “thunderbolt” and indrayudha or “Indra’s weapon.” As Indra is the warrior god of Vedic scriptures (the foundation of Hinduism, the symbol of the thunderbolt tells a lot about the Indian conception of diamonds. The flash of lightning reminds of the light that is reflected by a fine diamond octahedron and a diamond’s indomitable hardness.

This made the Golconda diamonds, the purest diamonds of the world. Due to this purity, unlike Type 1 diamonds, they allowed ultraviolet rays and visible light to pass through them and this gave them a clear, transparent nature. They were so clear and transparent that they looked like ice cubes. They gave an effect of water running through the gem. They were large in size too. They were weighed in units of rati where one rati was 7/8th of a carat. One of the stones from this region, the Great Mogul, is recorded to have weighed equivalent of 787 carats.

Carat, the unit to measure the weight of diamonds, comes from the Italian word carato or Greek word Keration, traceable to the Arabic qirat (horn) for the carob seed. Carob seeds have a small horn-like protrusion. All carob seeds are more or less of the same weight and hence could be used as a light weight measure for measuring small and light items such as gemstones. This concept of using carob seeds to measure gemstones is also traceable to India or the traditional Indian measure for diamonds was ratti where ratti is also a seed- where one rati was 7/8th of a carat.

The ratti seed is generally red with a black dot. They are also called gunja in Sanskrit and gurivinta in some of the South Indian languages. They are closely associated with Krishna temples in the Kerala tradition. Using ratti seed or in some cases, the real diamond itself, as the eye of idols, has been a practice of the land. Even today, only two percent of the world’s diamonds are considered to be of Type 2.

The legend of the Kohinoor diamond

The Kohinoor was once the world’s largest diamond, weighing 793 carats or 158.6 grams, when it was first mined near Guntur in India’s present-day southern state of Andhra Pradesh by the Kakatiya dynasty in the thirteenth century. It has been whittled down to a little over 100 carats over the centuries. The Kakatiya kings installed it in a temple, which was raided by Delhi Sultan Alauddin Khilji, who took it back to his capital along with other plundered treasures. It passed into the possession of the Mughal Empire that established itself in Delhi in the sixteenth century.

The Battle of Karnal (24 February 1739), was a decisive victory for Nader Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran, during his invasion of India. Nader’s forces defeated the army of Mogul tsar Muhammad Shah and appropriated his turban within three hours, paving the way for the Iranian sack of Delhi. In 1739, the Kohinoor fell into the hands of the Persian invader Nadir Shah, whose loot from his conquest of Delhi (and decimation of its inhabitants) also included the priceless Peacock Throne.

It was Nadir Shah himself, or so legend has it, who baptized the diamond the Kohinoor, or ‘Mountain of Light’. An eighteenth century Afghan queen memorably and colourfully stated, ‘if a strong man were to throw four stones, one north, one south, one east, one west and a fifth stone up into the air, and if the space between them were to be filled with gold, it would not equal the value of the Kohinoor’. Upon Nadir Shah’s death in 1747, the diamond fell into the hands of one of his generals, Ahmed Shah Abdali (Durrani), who became the Emir of Afghanistan. One of Durrani’s descendants was then obliged to cede the Kohinoor in tribute to the powerful Sikh Maharaja of Punjab, Ranjit Singh, in 1809. But Ranjit Singh’s successors could not hold on to his kingdom and the Sikhs were defeated by the British in two wars, culminating in the annexation of the Sikh domains to the British Empire in 1849. That was when the Kohinoor fell into British hands.

That was when the Kohinoor was supposedly “gifted” to the British. Stories abound on how Kohinoor changed the destinies of those who possessed her, for the worse, unfortunately, unless they were women. In this travel of Kohinoor and the travails of all those she lived with, Maharaja Duleep Singh was the last Indian king to have possessed this diamond. This prized diamond in her long history has travelled all over the world and been possessed by many rulers. She is known to have travelled back and forth within India and between India, Persia, and Afghanistan – changing hands from one ruler to another.

Maharaja Duleep Singh, one of the first freedom fighters of India against the British, was eventually tricked into parting with the Kohinoor under the Treaty of Lahore dated March 29, 1849. (The Treaty of Lahore was signed on 9 March 1846 after the First Sikh War. As part of the treaty, the Sikhs agreed to hand over Kashmir and Hazara and Jalandhar Doab to the British. It was due to this treaty that Kohinoor diamond was handed to the British.) The Sikh Kingdom of Punjab was annexed and merged with the British India dominions under this treaty. Duleep Singh was deposed, his treasury which comprised the Kohinoor, the Darya-i-Noor (Sea of Light) and Timur’s Ruby among other valuables, passed on to the hands of the British and finally reached Queen Victoria in England. They were showcased at the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851.

The diamond, which originally weighed 186 carats was cut down to 108 carats by the Queen and set in her crown. Since then, the Kohinoor continues to stay in the possession of the British Royalty locked away in the Tower of London. However in all this journey, Kohinoor was never bought or sold but changed hands only due to inheritance or as a token of gift or due to extortion, looting, trickery and treachery. In fact, it was only after reaching Persia, that she acquired the name Kohinoor.

Worth of Kohinoor Diamond

The Kohinoor’s value isn’t exactly known, but it is estimated to be worth €140 to €400 million. It is one of the most important diamonds in the world and is a part of the United Kingdom’s Crown Jewels. The Kohinoor’s diamond has a total weight of 109 carats.

Originally, the Kohinoor’s weighed 186 carats. The queen was dissatisfied with the stone’s luster and had it recut to in 1852 by renowned Coster Diamonds in Amsterdam. It is on display, along with the other British Crown Jewels, at the Tower of London, where the renowned Cullinan diamonds are also exhibited. The Kohinoor certainly isn’t the only one of its kind. Besides this particular super diamond there are other stunning stones, such as the Sancy Diamond, Hope Diamond and The Heart of the Ocean.

The Curse/Mythical Powers of the Kohinoor Diamond

Myths and stories are attributed to many legendary diamonds, such as the Sancy diamond and the Hope diamond. And so is to the Kohinoor too. Tradition has it that its owner will rule the world, but also that the stone would bring misfortune to any man wearing it.

Kohinoor was first mentioned in Indian literatures in the 17th century. Emperor Shah Jahan, the one who commissioned the building of Taj Mahal, also ordered the manufacture of the finest throne the world had ever seen. This was the famous Peacock Throne. The throne comprised a seat, canopy and pillars, and in pride of place sat two jeweled peacocks, one of which had the Kohinoor for a head, according to an article in UK based daily Telegraph. Following a failed assassination attempt, Shah Jahan grew increasingly violent and ordered the blinding of his son and heir. From that point he descended quickly into madness, and was himself beheaded by an assassin, feeding the idea of a cursed diamond.

The Kohinoor then passed into Afghan hands as plunder. Later the diamond returned to India, via the Maharaja of the Sikhs, Ranjit Singh in 1813. Singh, who ruled from Lahore, made the Kohinoor the symbol of his reign, proudly strapping it to his bicep. Singh ruled for another 26 years, following which he died peacefully in his sleep in 1839.

However, his successors- sons and grandsons- were all killed in a span of four years after his death. Five-year-old Duleep Singh, the youngest son of Ranjit Singh’s youngest queen, was the last Indian monarch to wear the Kohinoor on his plump little arm.

On 31 December 1600 Queen Elizabeth I founded the British East India Company, which over 150 years grew into one of the most powerful commercial enterprises in the world. The last Sikh Maharaja, Dalip Singh, found this out first-hand when he was forced to abdicate in 1849. The British took countless Royal Persian possessions back with them to England as spoils of war. The Kohinoor came into the possession of Queen Victoria from the treasury of Maharaja Ranjit Singh a few years before she was to be crowned Empress of India and played an important role in British coronations of the past. It will now take centre-stage in the new post-coronation exhibition at the Tower of London.

According to Danielle Kinsey, an assistant professor of history at Carleton University in Ottawa, that the rumours of the diamond being cursed were spread during its unveiling in the UK, positing that any man who wore the diamond would experience great misfortune and that, therefore, it could be worn only by a woman. And apparently, the Royal Family has heeded this legend. The diamond has since only been worn by women, including Queen Alexandra of Denmark, Queen Mary of Teck and the late Queen Elizabeth (wife of King George VI).

Ownership Controversy

Another, of course, is the return of some of the treasures looted from India in the course of colonialism. The money exacted in taxes and exploitation has already been spent, and cannot realistically be reclaimed. But individual pieces of statuary sitting in British museums could be if for nothing else than their symbolic value. After all, if looted Nazi-era art can be (and now is being) returned to their rightful owners in various Western countries, Why is the principle any different for looted colonial treasures?

The startling statement in early 2016 by Ranjit Kumar, the then Solicitor General of India — an advocate for the government — that the Kohinoor diamond had been gifted to the British and that India would not therefore seek its return, helped unleash a passionate debate in the country. Responding to a suit filed by a non-governmental organization, the All-India Human Rights and Social Justice Front, demanding that the government seek the return of the famed diamond, that the erstwhile Sikh kingdom in Punjab had given the Kohinoor to the British as ‘compensation’ for the expenses of the Anglo-Sikh wars of the 1840s. ‘It was neither forcibly stolen nor taken away’ by the British, declared the Solicitor General; as such there was no basis for the Government of India to seek its return.

The resultant uproar has had government spokesmen backpedalling furiously, asserting that the Solicitor General’s was not the final official view and a claim might still be filed. Indians will not relinquish their moral claim to the world’s most fabled diamond. For the Government of India to suggest that the diamond was paid as ‘compensation’ for British expenses in defeating the Sikhs is ridiculous, since any compensation by the losing side in a war to the winners is usually known as reparations. The diamond was formally handed over to Queen Victoria by the child Sikh heir Maharaja Duleep Singh, who simply had no choice in the matter. As pointed out in the Indian political debate on the issue, if one hold a gun to my head, I might ‘gift’ him my wallet — but that doesn’t mean I don’t want it back when your gun has been put away.

Reparations are in fact what many former colonies feel Britain owes them for centuries of rapacity in their lands. Returning priceless artefacts purloined at the height of imperial rule might be a good place to start. But the Kohinoor, which is part of the Crown Jewels displayed in the Tower of London, does pose special problems. While Indians consider their claim self-evident — the diamond, after all, has spent most of its existence on or under Indian soil — others have also asserted their claims. The Iranians say Nadir Shah stole it fair and square; the Afghans that they held it until being forced to surrender it to the Sikhs. The latest entrant into the Kohinoor sweepstakes is Pakistan, on the somewhat flimsy grounds that the capital of the Sikh empire, the undisputed last pre-British owners, was in Lahore, now in Pakistan. The fact that hardly any Sikhs are left in Pakistan after decades of ethnic cleansing of minorities there tends to be glossed over in asserting this claim.

The existence of contending claims comes as a major relief to Britain as it seeks to fend off a blizzard of demands to undo the manifold injustices of two centuries or more of colonial exploitation of far-flung lands. From the Parthenon Marbles to the Kohinoor, the British expropriation of the jewels of other countries’ heritage is a particular point of contention. Giving in on any one item could, the British fear, open Pandora’s Box. As former Prime Minister David Cameron conceded on a visit to India in July 2010, ‘If you say yes to one, you would suddenly find the British Museum would be empty. I’m afraid to say it [the Kohinoor] is going to have to stay put.’

And then there is a technical objection. In any case, the Solicitor General averred, the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972 does not permit the government to seek the return of antiquities exported from the country before India’s independence in 1947. Since the Kohinoor was lost to India a century before that date, there was nothing the government of independent India could do to reclaim it. Of course, the law could also be amended, especially by a Parliament that is likely to vote unanimously in favour of such a change, but that does not seem to have occurred to the government, which perhaps understandably fears rocking the bilateral boat. For the same reason, it has not sought to move the Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in case of Illicit Appropriation, a UN body that could help its case. The Indian Solicitor General’s stand seems to have taken the sail out of the winds of nationalists like myself who would like to have seen items of cultural significance in India returned as a way of expressing regret for centuries of British oppression and loot of India.

Still, flaunting the Kohinoor on the Queen Mother’s crown in the Tower of London is a powerful reminder of the injustices perpetrated by the former imperial power. Until it is returned — at least as a symbolic gesture of expiation — it will remain evidence of the loot, plunder and misappropriation that colonialism was really all about. Perhaps that is the best argument for leaving the Kohinoor where it emphatically does not belong — in British hands.

Public Display Controversy

In September 2022, it was speculated that Queen Camilla could be crowned with this crown, although there was speculation that a different crown might be used due to controversy around the Kohinoor after the Indian government said that Camilla wearing the diamond would evoke “painful memories of the colonial past”. It was, however, announced on 14 February 2023, that Queen Camilla would be crowned using the Crown of Queen Mary, without the Kohinoor diamond.

The controversial colonial-era Kohinoor claimed by India as a “Symbol of Victory” is set to open to the public in May as part of a new display of Britain’s Crown Jewels at the Tower of London. According to Historic Royal Palaces (HRP), the charity that manages Britain’s palaces, the new Jewel House exhibition will explore the history of the Kohinoor – through a combination of objects and visual projections.

The infamous diamond, set within the crown of the late Queen Elizabeth II’s mother, remains within the Tower after Camilla – in a diplomatic move – decided not to use this traditional crown for her coronation alongside King Charles II on May 6.

“The history of the Kohinoor, which is set within the crown of Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother, will be explored,” according to HRP in reference to the new planned display. “A combination of objects and visual inferences would explain the story of the stone as a symbol of conquest, with many previous owners including the Mughal emperors, the Shahs of Iran, the Emirs of Afghanistan and the Sikh Maharajas”.

“We look forward to expanding the story the Crown Jewels are telling and showcasing this remarkable collection to millions of visitors around the world,” according to Andrew Jackson, Resident Governor of the Tower of London and Keeper of the Jewel Home. “We are delighted to unveil our brand-new Jewel House display from 26 May, which provides visitors with a richer understanding of this magnificent collection. As the home of the Crown Jewels, we are delighted that the Tower of London The historic coronation will continue to play its part during the year,” he said.

The new exhibition will open a few weeks after the coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla, who will be crowned with the Queen Mary Crown. It is the first major change in more than a decade to the Jewel House in the Tower of London, which has been home to Britain’s Crown Jewels for nearly 400 years.

“The Crown Jewels are the most powerful symbol of the British monarchy and hold profound religious, historical and cultural significance. From their fascinating origins to their use during coronation ceremonies, the new Jewel House transformation will present the rich history of this magnificent collection with more depth and detail than ever before, according to Charles Farris, public historian of the history of the monarchy at HRP.

Some of the other changes will include the story of the famous Cullinan diamond, in which for the first time hammer and knife were used to cut the enormous diamond that would go on display in the Jewel House.

Discovered in South Africa in 1905, the diamond is the largest gem-quality uncut diamond ever found at 3,106 carats. It was divided into nine major stones and 96 smaller brilliants, with the largest two stones showing the British Sovereign’s scepter with the Cross and the Imperial State Crown.

At the heart of the new display will be a room dedicated to the community of the pageant, pageant and coronation procession. The display will present coronation processions throughout history, celebrating the contributions of the many people who participated in these unique events.

On display will be a range of items from the Royal Ceremonial Dress collection, including an exquisite court suit worn at the coronation of George IV and a heraldic tabard worn during royal processions.

The exhibit will conclude in the Treasury, the vault that protects most of the Crown Jewels collection, which includes more than 100 items in total. Among the magnificent items displayed in the Treasury is the St Edward’s Crown of 1661, used at the time of the coronation and the most important and sacred crown within the collection. The sovereign’s scepter with cross and the sovereign’s orb, presented to the monarch at the time of installation, are also displayed in the treasury. The new lighting will allow visitors to experience the world-renowned collection like never before, claims HRP in the re-presentation which is the culmination of a major four-year project.

Even though Kohinoor has been with the British crown, she is still referred to as the ‘Star of India.’ Living up to her name, this ‘mountain of light’ illuminates a glorious history of diamond trade in India. The trail might have ended, yet the story of the Kohinoor diamond remains intriguing. The Koh-i-Noor is not the preeminent diamondand had at least two comparable sisters – the Darya-i-Noor (Sea of Light), now in Tehran and estimated at 175-195 metric carats, and the Great Mughal Diamond, believed by most modern gemologists to be the 189.6-carat Orlov diamond, now set in Catherine the Great’s imperial Russian sceptre in the Kremlin. At present, the Koh-i-Noor is the 90th-largest diamond.

Indeed, on a 2010 visit to India, Prime Minister David Cameron declared outright that the Kohinoor would have to “stay put,” because “if you say yes to one, you would suddenly find the British Museum would be empty.” With Kumar having essentially taken Britain’s side on the Kohinoor issue, albeit for different reasons, nationalists are losing hope to get that priceless element of our heritage back. Britain owes us. But, instead of returning the evidence of their rapacity to their rightful owners, the British are flaunting the Kohinoor on the Queen Mother’s crown in the Tower of London. It is a stark reminder of what colonialism truly was: shameless subjugation, coercion, and misappropriation. Perhaps that is the best argument for leaving the Kohinoor in Britain, where it emphatically does not belong.