Africa Seeks Greater Flexibility For Delivery Of Russian Agricultural Products – OpEd

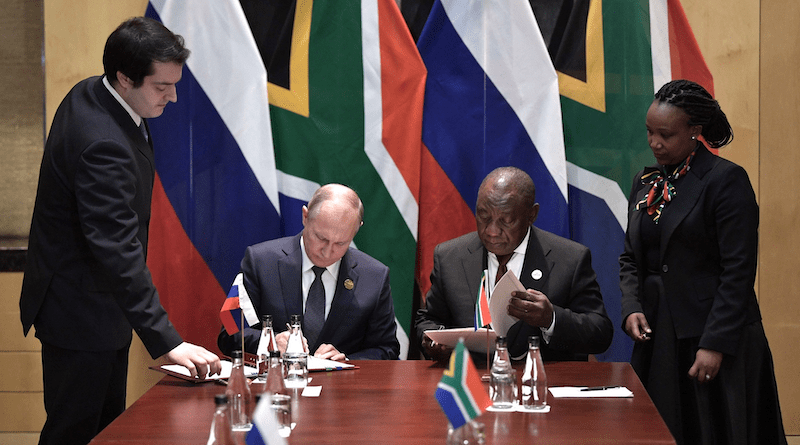

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa and the Comoro Islands Azali Assoumani (who now holds the rotating presidency of the African Union) together with four African leaders plan an early June special working visit to meet President Vladimir Putin. Local Russian and foreign media say the other African leaders include Senegal, Uganda, Egypt, the Republic of the Congo and Zambia.

The delegation plans to discuss an African peace-making initiative and negotiate for “no-cost deliveries” of grains, wheat and other agricultural products to a number of Africa countries. At South African Ramaphosa’s request for phone conversation on May 12, Putin discussed issues of Russian-South African relations of strategic partnership and expressed a desire to further step up mutually beneficial ties in various areas.

Putin reaffirmed Russia’s willingness to supply needy African countries with substantial amounts of grain and fertiliser at no-cost deliveries. At “no-cost deliveries” of agricultural products has featured in Putin’s speeches with African leaders since differences have arisen with the Black Sea Grain Initiative and questions relating to the prospects for settling the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

It was not the first time such “no-cost deliveries” was placed on the table. Putin spoke about this at the international parliamentary conference Russia – Africa in a Multipolar World which was held in Moscow under the auspices of the State Duma of the Russian Federal Assembly on March 20. In his speech, Putin stressed that “Russia is reliably fulfilling all its obligations pertaining to the supply of food, fertilisers, fuel and other products that are critically important to the countries of Africa, and ready to ensure their food security.

“You probably know that we are ready to supply some of the resources we have frozen in European countries to countries in need free-of-charge, including fertilisers. But unfortunately, there are obstacles here as well,” he told the gathering to an ear-deafening applause from African parliamentarians. “By the way, I would like to add that if we decide not to extend this grain deal after 60 days, Russia will be ready to supply under a deal, from Russia to the African countries in great need at no expense.” (Applause.)

The order of the issues primarily showed their importance during the phone conversation. Interestingly these African leaders have been unsuccessful in resolving their many conflicts at home, including in Sudan, Cameroon, Mali, Libya and Ethiopia. As the tussle for global influence intensifies, competition for winning the hearts and minds in strategic third countries is widening. Russia can afford to spoon feed Africa with the promise of free grains. And Africans are highly excited over the short-term food dependency on Russia. It is presumably soft-power gift to enlist their support for Russia, and against Ukraine and its Western and European allies.

As influence of Western countries diminishes and focus has shifted towards global south which includes Africa which rather needs an integrated economy and robust investment in sectors such as agriculture and industry – these are necessary to raise up its status away from dependency on global north. The two – agriculture and industry – are sectors necessary to support the newly established African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Behind this problem lies deep-seated social discontent and economic dissatisfaction among the large spectrum of the population and which constitute the active electorate. The existing economic deficiencies imply failure on election campaign promises and as a resultant there is always the lust for political regime change. African leaders should not depend on food packages, but adopt policies directed at the improving the economy. The scale of the challenges are there to overcome, though. The best way out is policy approach, consistency and state support combined with genuine external collaboration.

While a few outspoken African leaders shifted blames to Russia-Ukraine crisis, others tend to focus on spending heavy budget to import food to calm rising discontent among the population instead of using the financial resources on strengthening agricultural production systems.

In a sharp contrast to food-importing African countries, Zimbabwe has increased wheat production during this crucial time of Russia-Ukraine crisis. This achievement was attributed to efforts in mobilizing local farmers to improve the crop’s production. Zimbabwe is an African country that has been under Western sanctions for 25 years, hindering imports of much-needed machinery and other inputs to drive agriculture.

There are various local efforts to attain food security on the continent. For instance, the African Development Bank’s (AfDB) African Emergency Food Production Facility aims at increasing the production of climate-adapted wheat, corn, rice, and soybeans over the growing (planting) seasons in Africa. External players could invest in the aricultural sector rather than offering “no-cost deliveries” to African countries.

Significant to note that at one conference held by the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center in April 2022, African Development Bank Group President Dr. Akinwumi Adesina in Washington spoke about early successes through the African Development Bank’s innovative flagship initiative, Technologies for African Agricultural Transformation (TAAT) program, which operates across nine food commodities in more than 30 African countries. Supported largely by the United States, TAAT has helped to rapidly boost food production at scale on the continent, including the production of wheat, rice and other cereal crops.

Dr. Akinwumi Adesina said “the basic principle is that Africa should not be begging. We must solve our own challenges without depending much on others. Africa must rapidly expand its production to meet food security challenges.”

In a similar argument and direction, the World Bank has expressed worry over sub-Saharan Africa countries high expenditure on food imports, that could be produced locally using their vast uncultivated lands, and devastating impact on budgets due to rising external borrowing. According to the bank, it is crucial to increase the effectiveness of current resources to expanding and supporting local production especially in the sectors of agriculture and industry during this crucial period of Russia-Ukraine crisis.

With the above facts, African leaders have to demonstrate a higher level of commitment to tackling post-pandemic challenges and the Russia-Ukraine crisis that have created global economic instability and other related severe consequences. This requires collaborative action and much stronger pace of transformation to cater for the needs of the 1.3 billion population in Africa.

What do Russia and Africa share in common here? Putin valued the idea that African leaders are showing concern by participating in the Ukrainian settlement. This line of argument is what the South African leader pointed out that the Ukrainian crisis negatively impacts on Africa. It has triggered growing food prices, therefore the need to put forward an initiative, a peace initiative that could help to contribute to the solution of that conflict. What then are the implications when Putin offers “no-cost deliveries” of grain in exchange for an African peace initiative.

China has been offering to mediate possible peace talks, an offer clouded by its show of political support for Moscow. African leaders are interested in free deliveries and consequently, the African initiative is biased and could be considered as a tilted support for Moscow. African leaders have previously suggested diplomatic mechanism for peaceful settlement of the Russia-Ukraine crisis.

Last year in March, Senegalese President Macky Sall and the Chairperson of the African Union Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat, were the first to hold discussions with Russian President Vladimir Putin on the main aspects of the “special military operation” and on the importance of humanitarian issues, and suggested ending the conflict through diplomacy mechanism.

In the south-western Russian city of Sochi, Macky Sall and Moussa Mahamat together with Putin reviewed the Africa’s impending food crisis. Putin agreed to strengthen Russia-Senegalese bilateral ties and that of Russia-African relations. There was no breakthrough with the initiative proposed to end the crisis.

“We do not want to be aligned on this conflict, very clearly, we want peace. Even though we condemn the invasion, we’re working for a de-escalation, we’re working for a ceasefire, for dialogue … that is the African position,” Senegalese Sall said. “As you know, a number of countries voted for resolutions at the United Nations. The position of Africa is very heterogeneous but despite heavy pressure, many countries still did not denounce Russia’s position,”

In all there is one thing certain. Africa as a continent has remained a fertile ground for boosting investment in agriculture and industry but depends very much on food imports. Nevertherless, with no suitable alternative paths to Africa’s food security, Macky Sall had to complain: “Anti-Russia sanctions have made the situation worse and now we do not have access to grain from Russia, primarily to wheat. And, most importantly, we do not have access to fertiliser. The situation was bad and now it has become worse, creating a threat to food security in Africa.”

The Kremlin wants Kyiv to acknowledge Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and the Ukrainian provinces of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia, which most nations have denounced as illegal. Ukraine has rejected the demands and ruled out any talks with Russia until its troops pull back from all occupied territories. Ukraine is determined to recover all Russian-occupied areas.

According to reports, 17 African countries abstained from voting on the resolution at the United Nations. Some policy experts say this voting scenario at the UN opens the theme for a complete geopolitical study and analysis. Meanwhile, Africa is still divided over the crisis between Russia and Ukraine, the crisis has caused global economic instability since February 24, 2022. The African Union (AU) and African leaders understand aspects of the geopolitical complexities and implications of the existing conflict between Russia and Ukraine.