Remembering The Stonehenge Free Festival 37 Years On – OpEd

Happy summer solstice, everyone, wherever you are. I’m in London, where it’s overcast and drizzly, as it is across much of southern England, but although I’d love to be basking in the sun, I’m also rather enjoying how, today, Mother Nature is dominant in a different way, as a few people scurry about under umbrellas, while everything green and rooted happily soaks up the rain. In addition, although I’m hot at all happy about the economic hardship that an extra month of lockdown will mean for businesses that were hoping to reopen today, concerns about the rising numbers of Covid infections are genuine, and part of me is relieved that Boris Johnson didn’t succeed in declaring the summer solstice as ‘Freedom Day’, as he originally intended.

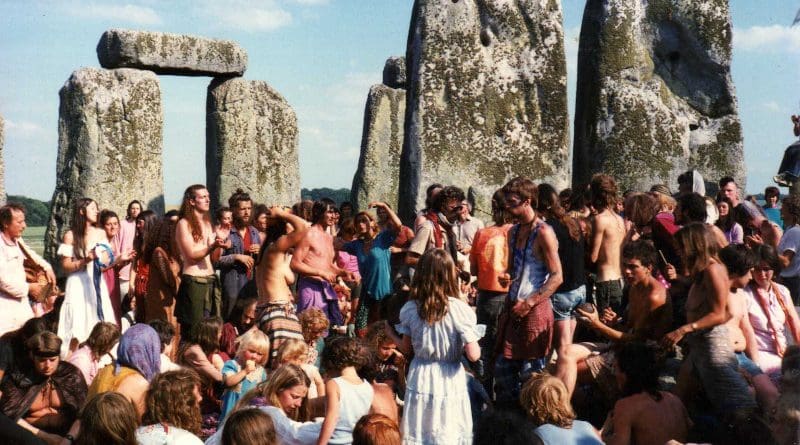

Today, like every summer solstice, I’m also thinking about Stonehenge, the ancient iconic temple in Wiltshire, where, on several occasions in my life, I’ve spent the summer solstice — twice at the Stonehenge Free Festival, in 1983 and 1984, and on five occasions from 2001 to 2005, at the ‘Managed Open Access’ events organised by English Heritage, the body that manages Stonehenge on behalf of the government.

Stonehenge, of course, remains enigmatic about issues of ownership, as it has done for thousands of years. Those who created it aligned its main axis on the summer solstice and the winter solstice, but left no written records to indicate what its purpose was, and over the years the state, archaeologists, neo-pagans, anarchists, festival-goers and curious members of the public have all staked a claim on its significance, and on its central cosmic axis.

My first visits to the temple, during the Stonehenge Free Festival, marked me for life. As a child of the ‘70s, growing up with a fascination for the counter-culture that first sprang prominently to life in the ‘60s, the free festival was an eye-opening assertion of another way of life, far, far removed from the model of the obedient “nuclear family” that Margaret Thatcher was pushing in response to the social and political upheavals of the previous decades.

As Thatcher figuratively burned the UK to the ground, re-establishing it as a nightmare of privatisation and greed, the festival represented a defiant alternative, both in its conscious efforts to create an alternative sense of community — nomadic, ecologically aware and close to the earth — and its rather less conscious hedonism and manifestations of social decay, as, accelerated by Thatcher, the old industrial model of the British economy gave way to one based on rampant financial opportunism, de-industrialisation, outsourcing and globalisation, which, along with the rise of materialistic self-absorption, has, in the decades since, largely corroded any viable notion of a coherent society.

After Thatcher crushed the Stonehenge Free Festival at the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985 in the most savage peacetime assault on unarmed civilians in modern British history, the summer solstice at Stonehenge was largely off-limits to those who felt that the ancient stones spoke to them for 15 long years, in which a militarised exclusion zone was generally set up and maintained every year, until, eventually, the Law Lords ruled that the exclusion zone was illegal, and English Heritage (and the National Trust, which “owns” the land around Stonehenge) responded by introducing ‘Managed Open Access’, allowing whoever wanted to to gather in the stones to witness the solstice sunrise from the night of June 20 until mid-morning on June 21.

I spent some lovely solstice mornings at Stonehenge in the early years of the 21st century — particularly the year of my first visit, 2001, when it was all so new, and in 2004 and 2005, when my books Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield had just been published, and I was publicising them.

I haven’t been since — largely, I confess, because the dominant materialism of our culture, and the confines of the event, eroded my ability to fully appreciate it as any kind of meaningful spiritual experience, especially in contrast to the autonomy of the festival years. However, every year I reflect on Stonehenge and the summer solstice, and this year, as ‘Managed Open Access’ was cancelled for the second year running, because of Covid (although some thoroughly committed would-be celebrants turned up, as they do every year), I’m taking the opportunity to post ‘STONED — Virtual Stonehenge 2020’, a video made by my friend Neil Goodwin, the co-director of ‘Operation Solstice’, the 1991 documentary about the Battle of the Beanfield.

Last year, contemplating the wreckage of live music and festivals because of Covid, Neil set up a Virtual Stonehenge Free Festival online, running from June 1, the day of the Beanfield, through to the solstice, with different festival areas, and a host of musicians seeking to capture something of the essence of festivals past.

I opened the festival speaking about the Battle of the Beanfield, on June 1, and played a few songs with my son Tyler beatboxing, and on the solstice my band The Four Fathers played a solstice set in our drummer’s garden in south London.

One of The Four Fathers’ songs is featured in the video, along with performances by a couple of dozen other musicians, all interspersed with archive footage of the festival, travellers and the Beanfield, and if you haven’t seen it before, I hope it provides you with an opportunity to capture something of the sense of community that Thatcher sought to crush, that materialism has tried to commodify, and that is currently struggling to survive because of Covid.