Vietnam, Key Piece Of America’s Indo-Pacific Puzzle – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Harsh V. Pant

In international relations, strategic turnarounds are not uncommon, and are in fact embedded in the very tapestry of anarchical structural realities. Yet, even by those standards, the immediacy and scale of the volte-face in relations between the United States and Vietnam since the Cold War has been remarkable.

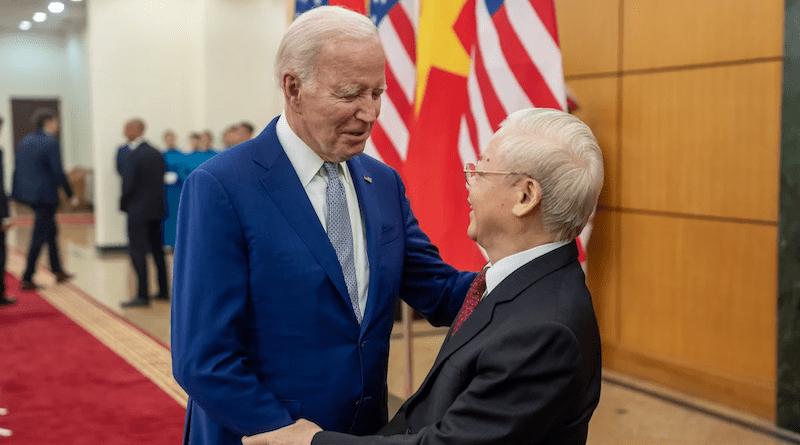

On September 10, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam Central Committee, Nguyen Phu Trong, and the U.S. President, Joe Biden, met in Vietnam during Mr. Biden’s visit, marking a new phase in the bilateral relationship between the two countries. The standout from this meeting was the elevation of U.S.-Vietnam relations to a U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership from a U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership forged in 2013 between Vietnam President Truong Tan Sang and U.S. President Barack Obama.

A complex foreign policy legacy

Given the complex history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam during the Cold War, this elevation marks a significant step up. Vietnam’s strategic restraint notwithstanding, motivations for an upgrade in bilateral relationship have existed on either side, at least since 2013, if not before. Vietnam’s reservations about entering into a strategic partnership with the U.S. have both contemporary and historical relevance.

The geopolitics involving China’s growing belligerence in the Pacific theatre, felt most palpably in the waters surrounding Vietnam and the broader South China Sea, has proven to be a first order deterrent for Vietnam’s great power engagements. On the other hand, the historical legacy of Vietnam’s contested relations with the U.S. during the Vietnam War, an axile relationship with the communist states China and the Soviet Union, culminating in the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with Soviet Union in 1978, had together imparted a direction diametrically opposite to U.S. interests. This complex foreign policy legacy is the reason why hitherto Vietnam has entered into a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ with only four nations: China, Russia, India and South Korea.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords signed in 1973 to end the Vietnam War. Much water has flown under the bridge, in that Vietnam’s relations with the U.S. have come a long way. Mr. Biden’s Indo-Pacific policy now counts Vietnam as among the U.S.’s ‘leading regional partners’ in the region. Vietnam is the 10th largest goods trading partner of the U.S. In 2020, the total value of trade in goods and services between the U.S. and Vietnam amounted to approximately $92.2 billion and exceeded $138 billion in 2022. In May 2022, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) was launched by the U.S., with Vietnam as a founding member along with 13 other countries to revive Washington’s economic dynamism in the Asia-Pacific.

Expanding ties

The Biden administration has depicted an unusual nimbleness in its strategic embrace of Vietnam. The visits by U.S. Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin and Vice President Kamala Harris to Vietnam in 2021, the meeting between Secretary Austin and Vietnamese Minister of National Defence of Vietnam General Phan Van Giang in Singapore in June 2022, and visits by U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen this year have culminated in Mr. Biden’s visit and augmenting of the bilateral relationship.

The U.S.-Vietnam relationship is now rapidly expanding its bilateral spectrum with an emphasis on enhancing political trust, strengthening science, technology, health and digital innovation cooperation, training of high-quality workforce, addressing climate change, and establishing a strong defence relationship in the backdrop of China’s increasing assertiveness. Addressing legacy issues underlines these cooperative efforts.

An assertive China

The war in Europe has thrown new challenges for Vietnam as its weapons import from Russia — its largest defence supplier — has been hit by West-led sanctions. These limitations in the face of Vietnam’s resolve to modernise its military, coupled with an ever-growing assertiveness from China, is also gradually nudging Vietnam in a new direction. China’s dramatic steps in 2014 to place oil rigs in Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone and subsequent assertive posturing have tested its avowed policy to stay clear of great power politics in the region. Undoubtedly, Washington senses an opportunity here and bolstering the defence and security relationship with Vietnam is a key piece of America’s grand strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

An important component of Mr. Biden’s visit was to start the process of friend-shoring supply chains in the semiconductor industry to Vietnam, even as it seeks to boost Hanoi’s chip manufacturing capabilities. As the two countries seek an expanded economic partnership by increasing investments in critical technologies, chips and Artificial Intelligence, there is space for linking such partnerships across the broader realms of the Indo-Pacific with like-minded partners. India’s initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) partnership with the U.S. along with the Quad’s Principles of critical and emerging technology could provide an overarching framework in the Indo-Pacific for a standardisation of technology in its design, development and use. A supply chain arch which extends from Vietnam to Europe via West Asia, and anchored by India with the newly-launched India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor during the recent G-20 meet in India could symbolise ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ in an apt way.

About the authors:

- Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. He is a Professor of International Relations with King’s India Institute at King’s College London. He is also Director (Honorary) of Delhi School of Transnational Affairs at Delhi University.

- Vivek Mishra is a Fellow with ORF’s Strategic Studies Programme. His research interests include America in the Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific and Asia-Pacific regions, particularly the role of the US in security in South Asia, Indo-US defence relations, and the Indian defence sector.

Source: This article was published by the Observer Research Foundation and originally appeared in The Hindu.