The Need For Bilingual Education In Afghanistan – OpEd

Although Afghanistan a linguistically diverse country, yet only two languages, Pashto and Dari, are used as mediums of instruction in schools. Bilingual education is, so far, alien to Afghanistan. This article will discuss the need for, and challenges of bilingual education in Afghanistan.

Specifically, I will discuss the amazing linguistic diversity in Afghanistan and then argue that there is a pressing need for experimenting with bilingual education in the country. By the use of the term experiment, I recognize that it will be a challenging and probably a significantly gradual process and that a quick-and-easy-fix is not going to be possible. Also, I will briefly reflect upon the benefits of bilingual education in the current literature and outline recommendation to the Afghan Ministry of Education regarding how to approach the inclusion of minority languages in education.

Language Diversity in Afghanistan

Afghanistan is home to East Iranian, West Iranian, Indic, Turkic, Mongolic, and Dravidian languages (Bashir, 2006; Barfield, 2010; Kieffer, 1983). Over 40 languages originated from these branches are spoken in the country (Lewis, Simons, & Fenning, 2013). Pashto and Dari hold the statutory status of national languages (Afghanistan Constitution 2004, Article 16) and the de facto languages of wider communication (Bahry, 2013).

The language ecology of Afghanistan is by far more complex than the one portrayed in the media (Schiffman, 2011). With Dari and Pashto as the de facto languages of wider communication, the inclination is that Dari is spoken when people from these two linguistic backgrounds communicate between them. Bahry (2013) adds that such an “asymmetrical bilingualism” is seen not only between Dari and Pashto but between other minority languages too.

For instance, Brahui language speakers tend to communicate in Balochi language with Balochs as opposed to communicating in Brahui with them. Bahry (2013) therefore proposes that it would be more accurate if language dynamics of Afghanistan are looked at in the frameworks of ecology, diglossia and bilingualism, and language hierarchy. Another feature of different linguistic groups in Afghanistan is that they have historically been lived among their own groups with little cross-group interaction. Furthermore, different ethnic groups have engaged in civil war that for a period in 1980s and 1990s was fueled more by ethnic rather than ideological differences.

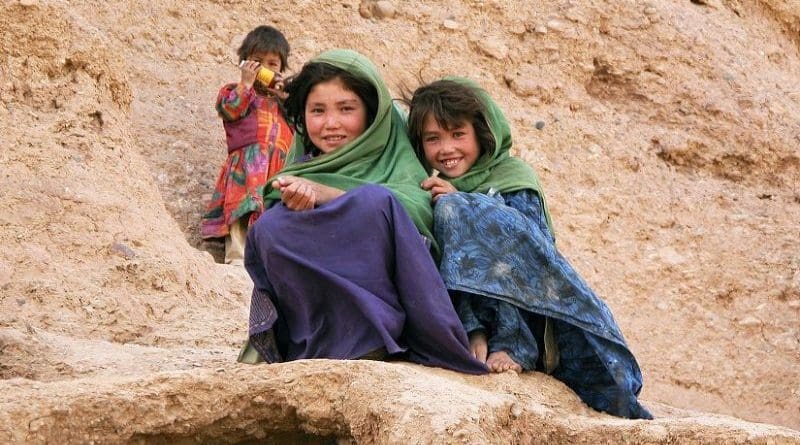

Another recent urgent issue in Afghanistan is the internal displacements as people flee conflict from different parts of the country. These people mainly head towards provincial capitals and Kabul. Some of internally displaced kids are transferred from schools in their native community to schools where they have migrated.

The issue, though, is that these kids are especially vulnerable because they usually come from a comprehensively ethnically monotonous communities to cities that are diverse but where their mother tongue is often not the language of instruction. Parents of such kids, often do not want to send their kids to schools because they feel that children have already gone through an intensive emotional experience of fleeing a warzone and that attending schools in a second language would only add to their feeling of segregation and marginalization.

Despite the diverse, complex, and complicated linguistic context, students that come from linguistic backgrounds other than Pashto and Dari, have to go to schools where their mother tongue is not the language of instruction. Not only has this implications for students’ learning achievements and psychological wellbeing, but has consequences for social integration and community involvement in education.

Mother-Tongue Based Education Debate in Afghanistan

Historically, as said earlier, only Pashto and Dari served as mediums of instructions in schools However, when Hanif Atmar sworn in as the minister of education in 2006, he promised to provide mother-tongue education in Afghanistan. The reform could not, however, be considered a mother-tongue based bilingual education initiative for following reasons.

First, the reform did not include minority languages in a sort of bilingual education classes in which two languages are to be used in some specific proportions at the same time. Instead, classes were segregated. For example, in Kabul, Pashto speaking students were segregated from Dari speaking students and then, they had to get education in only one language. This is not, by definition, bilingual education.

It is particularly interesting that people’s reaction to this reform was rather ambivalent. At the time, I was a student of grade 12 and I remember teachers, students, and analysts interviewing by radios would exhibit mixed reactions: some said it was a positive move because it was students’ right to be educated in their mother tongue while others commented that it would have negative consequences in relation to ethnic unity and expressed concerns about the capacity of the MoE in effectively implementing the reform.

It is important to note that this reform cannot be considered bilingual education because in bilingual education, instead of one language in a class or instead of having segregated classes for different languages, two languages are used at the same time in instruction in a class in some specific proportions. In spite of the reform initiative being not complete and its ineffective implementation, it nonetheless challenged the status quo and initiated the mother-tongue based education discourse in Afghanistan.

The relevance of Bilingual Education

Considering the sparse distribution of population in Afghanistan and, except for large cities and provincial capitals, the tendency that people of individual linguistic backgrounds live together with relatively less intergroup interaction; it can safely be assumed that at least minority languages speaking children in early grades struggle with Pashto and Dari. Therefore, it follows that the MoE should take bilingual education more seriously.

Students benefits from bilingual education in two, quantifiable, and non-quantifiable ways. The quantifiable benefits to students include increased enrollment, improved attendance, improved retention, higher test scores, better acquisition of second language while also retaining their first language (e.g., Kosonen, 2005; Ball, 2010; Cummins, 2000; King & Mackey, 2007). In general, It is reported that when children are enrolled in mother-tongue education, they develop certain types of perceptive and metalinguistic awareness sooner and better than those who are enrolled in schools where language of instruction is different from their mother tongue (e.g., Bialystok, 2001;King & Mackey, 2007).

On the other hand, there are non-quantifiable benefits to children. For instance, bilingual education brings about access to an emotionally enabling learning environment that fosters psychological and emotional well-being of students which leads to improved self-esteem and motivation (Wright & Taylor, 1995; Rubio, 2007). This then results in smooth transitioning between home and school (Kioko, Mutiga, Muthwii, Schroeder, Inyega, & Trudell, 2008). When children do not have access to bilingual education, they feel the discontinuity between home and school culture which leads to their lower self-esteem and poor motivation leading to overall poor academic achievements (Baker & Prys Jones, 1998).

Its relevance is even further signified considering the continuous push for community-driven development (CDD) in Afghanistan. Afghanistan launched the Citizen’s Charter (CC) National Priority Program recently. CC envisions the provision of basic services (education, health, infrastructure, agriculture) to remote communities with the help from and support of local community councils such as Community Development Councils (CDCs), School Management Shuras (SMSs) and Education Sub-Committees (ESs).

This is particularly important because against the backdrop of increased security concerns and entrenched state capacity, the role of local councils that comprise of local people has increased. The government strives to enable communities to plan and monitor service provision to the people, particularly, in remote areas.

Specifically in education, there are two local councils involved: SMS and ES. SMS is comprised of common villagers, teachers, and students. An SMS monitors education provision in a school and support school administration with provision of in-kind contribution and advisory role. ES on the other hand has the same functions for a community based education class.

MoE has lately placed immense emphasis on the importance of community participation in education through these councils. In fact, the MoE has established a district department called the Department of Social Mobilization and School Shuras (DSMS) to strive to engage communities and local people in education provision and oversight. The MoE can effectively engage all communities only when these communities have a sense of belonging to schools and if their languages are given importance, they would be more likely to be mobilized.

While it is true that parent may still prefer the learning of Pashto or Dari over their minority languages, however, considering the fact that bilingual education does not replace Pashto and Dari with other languages but, as discussed earlier, will even result in more effective acquisition of these languages by minority language speaking students. Therefore, once communities realize that bilingual education is not subtractive but additive in terms of language acquisition, they will welcome the reform and will be happy with it because, as I have explored this, parents want their children to along with learning Pashto and Dari, they need to learn their first language too.

The Inclusion of Minority Languages in Education – a Proposed Approach

It is critical to understand that inclusion of minority languages in a bilingual education model in Afghanistan is going to be characterized by genuine logistical and financial challenges. The challenges MoE faced in implementing the teaching of languages textbooks for six additional third official languages is a clear testimony to this as the relatively easy-to-implement reform of teaching language textbook at schools for those six languages turned out to be heavily characterized by challenges which have persisted up to the present day.

Pashai’s grammar, for example, was written for the first time in 2014 as a doctoral dissertation (Rachel, 2014). Furthermore, there are four varieties of Pashai, and intriguingly they share only 30% lexical similarity: north-eastern, northwestern, southeastern and southwestern (Lewis, Simons, & Fenning, 2013).

Considering all this, it is clear that developing a textbook for Pashai was not an easy job. When it was printed and distributed to Pashai speaking areas, it came to light that it was written in Southeaster dialect and so teachers could not teach it in areas of three other dialects. It was therefore distributed but recalled back from majority of Pashai speaking areas. Although the issue with Pashai textbook could be the extreme case of it, but it is safe to say that the MoE faced similar challenges with other six third official languages also.

Not only that, having segregated classes for Pashto and Dari in Kabul faced extreme challenges. I was working with the MoE as Structure Development Manager in the year 2011 and we had an official tour in Kabul city to explore what support schools needed. Almost every school that had established segregated classes to accommodate Pashto education, was struggling with having qualified teachers who could teach Pashto. Teachers and parents believed that after almost five years of the reform, teaching quality in Pashto was still way more inferior compared to teaching in Dari.

Frequently cited reasons for this included, among many more, the limited number of teachers, inability to hire new teachers who could teach in Pashto, unavailability of textbooks in Pashto, the capacity of school administrations to effectively oversee education in Pashto.

I therefore propose a gradual process in which the MoE will take on only six third official languages in stage one. Stage one shall, in turn, have different sub stages in the sense that one language shall be included in bilingual education with Pashto or Dari in only one area. This way, the MoE will be able to focus on only one additional language in only one area for at least a couple of years.

For example, the MoE may only start with Uzbeki language which is considered to be the third largest language after Pashto and Dari. The MoE may only introduce bilingual education in Jozjan province where Uzbek ethnic group is form the overwhelming majority of local residents. This way, the MoE can pull in material resources, time, and expertise to ensure there is a smooth transition into bilingual education in one language in one area. MoE can only take on another language once it has ensured there is flawless bilingual education in Uzbeki.

I propose mother-tongue based bilingual education method in which, for example, Uzbeki and Dari will be used in some specific proportions. In grade one, the use of Uzbeki to Dari could be 9 to 1. This shall reverse with each subsequent grade and by reaching grade five this could become 1 to 9 and ultimately in grade six, students will transition into Dari-only education. This way, there will be a smooth transitioning from a bilingual to monolingual education and by grade six, students will have already learned their mother tongue and will have developed cognitive skills in their own language.

Additionally, Dari or Pashto speaking students will have also learned Uzbeki by grade six. This type of bilingual education has been preferred as it is considered to be the best approach (Collier & Thomas, 2004)

Given that developmental efforts in Afghanistan are still considerably reliant on international donors, it is therefore critical to initiate the discourse on the relevance of bilingual education first so that there is a consensus between the Afghan ministry of education, non-governmental organization that are active in education service delivery in collaboration with the ministry, and international donor agencies such as USAID and UNICEF.

It is baffling that UNESCO has been actively advocating for bilingual education globally but there is still little discourse on the relevance of bilingual education in Afghanistan in reports by UNESCO and other international organizations such as the World Bank. I strongly believe that it’s time to experiment with bilingual education in Afghanistan first by initiating an honest discourse among the ministry and other partners followed by gradual albeit committed process of including minority languages in a form of bilingual education in Afghanistan and I hope that this article will contribute into initiating such a discourse. When it is decided to have bilingual education in Afghanistan, it is important for the ministry of education to initiate a public awareness program so that the reform is viewed favorably by education service providers as well as communities and the public at large.

*Abdul Hamid Hatsaandh has a master’s degree in Education Policy candidate at Harvard University and is a Fulbright Scholar from Afghanistan.

Bibliography

- Afghanistan (2004). Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. (http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/af00000_.html)

- Afghanistan (2004). Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. (http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/af00000_.html)

- Bahry, S. A. (2013). Language in Afghanistan’s Education Reform. In Language Issues in Comparative Education (pp. 59-76). Sense Publishers, Rotterdam.

- Baker, C., & Prys Jones, S. P. (1998). Encyclopedia of bilingualism and bilingual education. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters

- Ball, J. (2010). Enhancing learning of children from diverse language backgrounds: Mother tongue-based bilingual or multilingual education in early childhood and early primary school years. Victoria, Canada: Early Childhood Development Intercultural Partnerships, University of Victoria.

- Barfield, Thomas J. (2010). Afghanistan: A cultural and political history. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Bashir, Elena (2006). Indo-Iranian frontier languages. Encyclopedia Iranica, Online Edition, November 15, 2006

- Benson, C. (2002). Real and potential benefits of bilingual programmers in developing countries. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 5 (6), 303-317

- Bialystok, E. (2001). Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy, and cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bühmann, D., & Trudell, B. (2008). Mother tongue matters: Local language as a key to effective learning. France: UNESCO.

- Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (2004). The astounding effectiveness of dual language education for all. NABE Journal of Research and practice, 2(1), 1-20.

- Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of educational research, 49(2), 222-251.

- Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Education Law of Afghanistan (2008).

- Kieffer, Charles (1983). Afghanistan. V. Languages. Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 5, 501- 516.

- King, K., & Mackey, A. (2007). The bilingual edge: Why, when, and how to teach your child a second language. New York: Collins.

- Kioko, A., Mutiga, J., Muthwii, M., Schroeder, L., Inyega, H., & Trudell, B. (2008). Language and education in Africa: Answering the questions. Nairobi: UNESCO.

- Kosonen, K. (2005). Education in local languages: Policy and practice in Southeast Asia. First languages first: Community-based literacy programmes for minority language contexts in Asia. Bangkok: UNESCO Bangkok.

- Lehr, Rachel. 2014. A descriptive grammar of Pashai: The language and speech of a community of Darrai Nur. Phd dissertation, University of Chicago.

- Pinnock, Helen (2009). Language and education: The missing link. Reading and London, England: CfBT Educational Trust and Save the Children UK.

- Rubio. M-N. (2007). Mother tongue plus two: Can pluralingualism become the norm? In Children in Europe, 12, 2-3.

- Schiffman, Harold (Ed.) (2011). Language policy and language conflict in Afghanistan and its Neighbors. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill

- Simons, Gary F. and Charles D. Fenning (eds.). 2017. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twentieth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://ethnologue.com.

- Skutnabb-Tangas, T., & Toukomaa, P. (1976). Teaching migrant children’s mother tongue and learning the language of the host country in the context of the sociocultural situation of the migrant family. Helsinki: Tampere.

- UNESCO (2008a). Mother Tongue Matters: Local Language as a Key to Effective Learning. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO (2008c). Mother Tongue Matters: Local Language as a Key to Effective Learning. Paris: UNESCO.

- Wilson, W. H., Kamanä, K., & Rawlins, N. (2006). Näwahï Hawaiian laboratory school. Journal of American Indian Education, 42-44.

- Wright, S. C., & Taylor, D. M. (1995). Identity and the language of the classroom: Investigating the impact of heritage versus second language instruction on personal and collective self-esteem. Journal of educational psychology, 87(2), 241.