ASEAN-US Relations: Rhetoric Versus Reality – OpEd

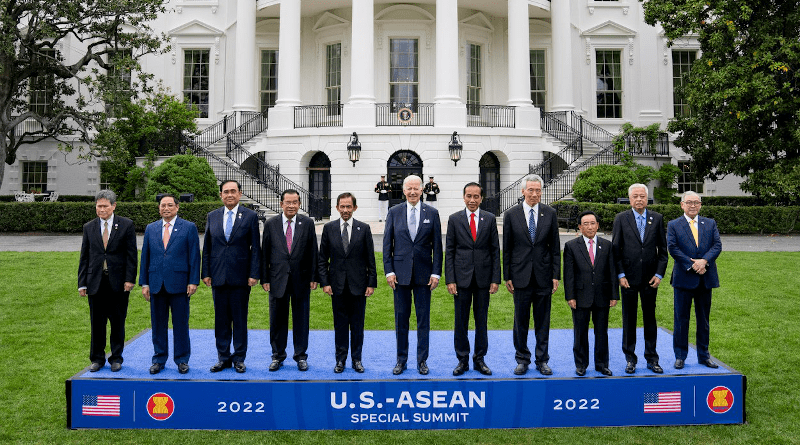

In the run up to the May 12-13 ASEAN-US Summit in Washington, both sides had fond hopes for what might be achieved. However their hopes foundered on the rocks of reality.

Despite its rhetoric to the contrary, for the U.S. this meeting was all about China and the US effort to form a united front against it in their struggle for regional domination.

ASEAN wanted to extract robust US commitments to its regional centrality in political and economic affairs as well as to actions that demonstrate that the US interest in it will not fade in favor of Europe. Some had even hoped that the U.S. would court ASEAN for its own merits rather than as a pawn in the US-China strategic struggle.

The highlight of the meeting was an agreement to establish a US-ASEAN Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. But the U.S. needed this to place its relations with ASEAN on the same level as that of ASEAN’s with China. Ironically this symbolized their intensifying competition for ASEAN’s hearts and minds and how far the U.S. has fallen behind.

The U.S. has previously made its intentions crystal clear. It views its contest with China as one of democracy (good) versus authoritarianism (evil). The goal of its Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) is to prevent China’s regional hegemony by building greater coordination with allies and partners “across war-fighting domains” to ensure allies can dissuade or defeat aggression in any form_.” This means that its success depends on a US-centric network of security allies and partners and their willingness to go along with it in confronting China. The summit was part of this US effort to build a united front against China.

But ASEAN and the U.S. have fundamentally different visions for the region. The U.S. vision of an implicitly anti-China, security-oriented Free and Open Indo-Pacific contrasts with ASEAN’s inclusive [including China], more economic, less militaristic Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. ASEAN hopes the US and China can coexist and refrain from raising tensions that hurt them.

The fact that their Joint Vision Statement issued at the end of the meeting did not mention either construct reflects agreement to disagree.

ASEAN also wants the U.S. to make its actions consistent with its rhetoric of supporting ASEAN centrality in regional security affairs. ‘Centrality’ here “refers to the role of ASEAN as a regional leader or driver, convenor or facilitator, hub or key node_ _”. During the meeting, US President Joe Biden declared that “strengthening the US relationship with ASEAN is “at the very heart of [US] foreign policy strategy”. Perhaps that is so. But the goal of that strategy is to constrain and contain China and that is not necessarily in the interests of ASEAN or all its members.

Indeed, ASEAN and its members were already wary of US-driven realpolitik strategic moves like the US and UK agreement to share nuclear submarine and other advanced technologies with Australia (AUKUS) and the ad hoc security dialogue between India, Japan, Australia and the U.S. (the Quad). The U.S. and its allies initiated these clusters to counter what the U.S. sees as the “China threat’ to its hegemony in Asia. But in doing so, they went around and over ASEAN to form these pacts. As a result, ASEAN has been split and its centrality undermined.

As another example of US centrism, the US managed to insert in the Joint Vision Statement its concern with “ensuring “freedom of navigation and over flight and other lawful uses of the seas”. The latter is code for asserting what it considers to be its right to undertake provocative intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance probes in China’s Exclusive Economic Zone—but also including that of ASEAN states themselves.

The Joint Vision Statement reflects these contradictions. Indeed, it is remarkable more for what is missing or left ambiguous rather than included and clear. The parties agreed to “appropriately [emphasis added] cooperate in international and regional fora”. But what is ‘inappropriate’ cooperation? Clearly, either or both had reservations regarding certain types of cooperation . But which types and why?

They declared that they “look forward to further strengthening cooperation including through relevant initiatives or frameworks of the United States or ASEAN.” This ambiguity appears to reflect real differences or uncertainties as to which side should take the initiative on what issues. For example, the U.S. seems to want to fit ASEAN in to the ‘Quad’. But ASEAN centrality means its security architecture and forums should take precedence and the Quad should take direction from them.

ASEAN wants the U.S. to place more emphasis on US-ASEAN economic relations. Indeed, the most important single thing the U.S. could do to appeal to ASEAN members would be to lead and coordinate a multinational effort of economic assistance in a strategic manner focusing on needs defined by the recipients.

Yet it missed the opportunity to announce its long awaited Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). It was not even mentioned in the Joint Vision Statement. Instead it will be announced by Mr. Biden in Tokyo this week at a meeting of the Quad. This only reinforces the notion that “ASEAN is not a fulcrum for US economic co-operation in the Indo-Pacific”. Although ASEAN wanted to participate in its formulation, it apparently was not consulted.

The benefits to ASEAN are not clear. The IPEF is “not a traditional trade agreement and will not grant enhanced reciprocol market access.” Rather it is “all about rules and standards” in four areas—fair trade, supply chain resilience, infrastructure and decarbonization, and anticorruption. States can sign up to one or more of these modules but must accept all of those module elements. Some may not be able to meet all the standards for particular modules such as labor, tax, data privacy or anticorruption. Of ASEAN members Singapore and the Philippines are expected to sign up for negotiations under IPEF.

Moreover there is concern that the IPEF will be focused on issues more important to the U.S. and its strategy to exclude and contain China rather than ASEAN members’ urgent needs. Further, because of the ephemeral nature of previous US commitments to Asia like the ‘pivot’, there is suspicion that the IPEF will not outlast the Biden administration.

This concern was reinforced by the US announcement of a paltry US 150 million aid pledge compared to 1.5 billion from China. Moreover the 150 million includes nearly half for US Coast Guard assistance in presence, training and equipment to ASEAN countries. This will increase maritime domain awareness that is to the U.S. advantage in its long term struggle against China. While not as provocative to China as the US Navy, it signifies ASEAN acceptance of a US security presence.

The U.S. is losing the economic and thus influence contest with China. Although it leads in investment in the region, China trade value with ASEAN is twice that of the U.S. The U.S. needs to bring more to the table to reverse that trend.

On the interpersonal level, Mr. Biden declined bilateral meetings with most of the leaders. His administration claimed this was to emphasize that he was meeting with ASEAN as an institution. Given that they had traveled half way around the world to meet him, I suspect some were miffed. This was a missed opportunity to establish the personal rapport with some of leaders that is so important in Southeast Asia.

A major flaw in this approach is that ASEAN is not united on political issues. This is clearly demonstrated by its members’ diverse responses to the crisis in Myanmar and Ukraine and even to China’s behavior in the South China Sea. They are only united in that they do not want to be forced to choose between China and the U.S.. Indeed, they do not want to become puppets or designated proxies for either one as happened during the US-Soviet Union Cold War with disastrous results for some of them—like Vietnam. But it is not clear from this summit that the U.S. will help them avoid that fate.

Some parts of this piece first appeared in the Asia Times, https://asiatimes.com/2022/05/asean-us-summit-rhetoric-versus-reality/ and in Pearls and Irritations https://johnmenadue.com/the-asean-us-summit-rhetoric-versus-reality/