Mr. Zelenskyy Goes To Washington: So What Did He Get From It? – Analysis

By RFE RL

By Mike Eckel and Todd Prince

Volodymyr Zelenskiy got a ride in a U.S. government jet, a red-carpet welcome at the White House, and more than a dozen standing ovations from members of Congress — plus nearly $2 billion in new weapons — including a Patriot air-defense system, which Ukraine’s government hopes to use in defending its battered power grid from Russian missile barrages.

But did the Ukrainian president get what he really wanted?

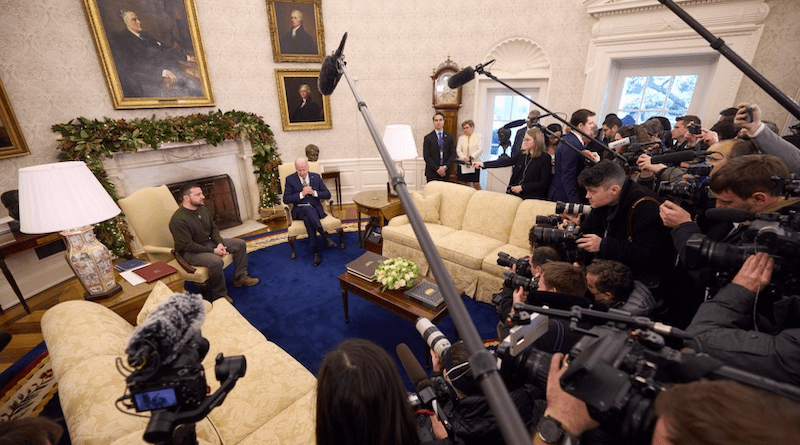

That Zelenskiy’s reception in Washington was near-rapturous was clear, even before he addressed a joint session of Congress. President Joe Biden’s administration pulled out all the stops to welcome the Ukrainian leader, including authorizing a U.S. Air Force jet — a government plane typically used for cabinet secretaries and other dignitaries — to fly him from Poland to Washington, D.C.

For some observers, the imagery evoked parallels to a visit 81 years ago this week, when British Prime Minister Winston Churchill made a wartime visit to the U.S. capital and received a “roaring reception” from Congress and President Franklin Roosevelt.

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine entering its 11th month, grinding into a winter of attrition with no end in sight and with U.S. resolve flagging, the question now is whether Zelenskiy got what he was seeking: a long-term U.S. commitment of aid and weaponry for a distant war in spite of persistent U.S. skepticism.

“Zelenskiy is trying to solidify relations with his major supporter for what he now recognizes is going to be a long war,” said Mark Cancian, a military analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “This isn’t about getting through the next month or two; this is about the next year,” he said. “He wants to lock down the relations.”

It was unclear whether Biden agrees with Zelenskiy on Kyiv’s demand to push Russian forces out of all Ukrainian territory, including Crimea, says Orysia Lutsevych, director of the Ukraine Forum at Chatham House, a London-based research organization.

Whether Biden comes around to that position depends “on how skillfully” the Ukrainian armed forces use the limited military capabilities they have. “Zelenskiy tries to persuade the U.S. leadership that Ukraine can win this war,” Lutsevych said. “We will see what kind of offensive assistance will be provided as part of new $45 billion package when it is approved.”

“All in all, Kyiv was given a magnificent possibility to make its case,” she said.

U.S. support for Ukraine indeed is waning, though solid majorities continue to back supplying Kyiv with weaponry, accepting Ukrainian refugees, and imposing economic sanctions on Russia. Fewer Americans support an open-ended commitment compared with just four months earlier, however, and a growing number want the United States to do more to pressure Kyiv to enter peace talks.

Ukraine was not central to last month’s U.S. congressional elections, not by a long shot. Still, Republicans will control the House of Representatives come January, and a small number of lawmakers have pledged a harsh scrutiny for aid being sent to Ukraine.

Overall, however, the effort continues to draw large majorities, Republicans and Democrats, House and Senate.

That explains the message of pragmatism that Zelenskiy tried to convey in his 22-minute speech from the podium in the House chamber. “Your money is not charity,” he told lawmakers, speaking in English. “It’s an investment in the global security and democracy that we handle in the most responsible way.”

In terms of tangible results, Zelenskiy ended up with $2 billion of new weaponry and equipment, including the Patriot missile system. But he came up empty-handed for other requests for now: F-16 fighter jets, M1 Abrams tanks, or longer-range ATACMS missiles — a reflection of the Biden White House’s wariness of further escalation.

On the other hand, Zelenskiy also dodged any public push from Biden or other elected officials for concessions on peace talks, something that some Ukrainian commanders, emboldened by battlefield successes, are loath to consider while Russia occupies 20 percent of its territory.

Still, he tried to signal to Congress that his administration was not outright opposed to peace. “We need peace, yes,” he said in his speech. “Ukraine has already offered proposals, which I just discussed with President Biden, our peace formula, 10 points which should and must be implemented for our joint security, guaranteed for decades ahead, and the summit which can be held.”

Secret Trips, East And West

The day before embarking on the secret journey to Washington — his first outside of Ukraine since the invasion in February — Zelenskiy made another, equally secretive trip: to Bakhmut, the frontline Donbas city that is currently the site of the fiercest fighting in Ukraine.

There, he gave a pep talk to officers and troops facing relentless assaults, mainly by soldiers from the notorious Russian mercenary company, the Vagner Group.

He also received a Ukrainian flag covered in black-ink messages scrawled by soldiers, a flag he later presented to congressional leaders in an unmistakable symbolic punch.

“They asked me to bring this flag to you, to the U.S. Congress, to members of the House of Representatives and senators whose decisions can save millions of people,” Zelenskiy said in his final words to lawmakers. “So let these decisions be taken. Let this flag stay with you. Ladies and gentlemen, this flag is a symbol of our victory in this war.”

Zelenskiy’s visit was “more like an investment that is going to bring results in future,” said Mykola Byelyeskov, a research fellow at the National Institute for Strategic Studies, a government-backed think tank in Kyiv. “When you make investments, you don’t expect deliveries on the same day,” he said. “Treat Zelenskiy’s visit the same way. It’s a kind of boost whose effects we are going to see somewhere in future.”

“The most important thing is that, here in D.C., is the president of a country which, precisely one year ago, was written off in terms of an army-versus-army contest,” he said. “But in the end, it managed to continuously defy expectations.”

“The big issue [for Zelenskiy’s trip] is that President Biden should understand in his mindset that Ukraine is capable of winning this war and that Ukraine losing [would] mean much higher risks for the U.S. than for Russia losing,” said Darya Kalenyuk, a Kyiv-based anti-corruption activist who regularly meets with U.S. officials.

John Herbst, a former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine and a longtime supporter of increased support for Kyiv, echoes Zelenskiy’s arguments, saying aid to Ukraine is a “smart and economical” policy to boost U.S. security.

“This is a smart and economical place for us to stop Putin’s aggression,” he said. “It’s not simply a gift or principally a gift to the Ukrainian people from the U.S. This is the smart way for the U.S. to defend its security and prosperity. A Putin who’s threatening Europe is a Putin who’s endangering American security and American wealth.”

In his speech to Congress, Zelenskiy made it a point to pull on lawmakers’ heart strings, referencing symbolic moments in U.S. history. He likened the battle for Bakhmut to the Battle of Saratoga during the American Revolutionary War. And he cited the Battle of the Bulge, the Nazi counterattack against U.S. forces in December 1944.

In doing so, he spoke directly to Americans in several ways, says Elise Giuliano, a professor of political science at Columbia University’s Harriman Institute.

“First by talking about lofty ideals that appeal to Americans such as this is a fight against tyranny. And a fight against democracy,” she said. “But also talking to Americans in really concrete terms saying: ‘This is about terrorist states — Russia and Iran — joining together to break international borders. But our world is an interconnected world. It’s interdependent, and no one is safe from states that act this way. Don’t think an ocean can protect you.'”

“So he’s kind of appealing to our interest in protecting democracy, but also in security,” Giuliano said.

In many ways, Zelenskiy’s surprise trip to the United States is in keeping with how Ukraine has waged its fight against Russia, repeatedly surprising the West in its ability to outflank, to outgun, and even outmaneuver the larger, more powerful Russian military.

In the run-up to the February 24 invasion, few in the West expected Ukraine to hold out for more than a couple days, with the expectation that Kyiv would fall, Zelenskiy would flee, and Ukrainian forces would capitulate.

Instead, Ukraine has forced Russia to make at least three major battlefield retreats, successes powered by Western weaponry combined with Ukrainian ingenuity and tenacity.

Despite cold temperatures and miserable battlefield conditions, Ukrainian commanders have hinted more counteroffensives may be in the offing, something that would further defy Western expectations.

As with previous shipments, the decision to supply Kyiv with the Patriot air-defense system, to help thwart the Russian aerial pummeling of Ukraine’s infrastructure, plus nearly $2 billion in weapons — things like ammunition for HIMARS long-range precision artillery, radar-seeking missiles, and thousands of mortars — is intended to be a tangible manifestation of U.S. policy.

And it dovetails with a larger, $44 billion Ukraine-related aid package tucked into a giant annual spending bill that must pass in order for the U.S. government to remain open and functioning. Assuming the package makes it through congressional negotiations, that will mean U.S. aid to Ukraine since the February invasion will total more than $100 billion.

Taken together, it all means the United States is in even deeper than before — with no end in sight.

“Things are pretty quiet on the battlefield, so this is a time when he can leave,” Cancian said of Zelenskiy’s visit.

“There was a window when he could be out of the country,” he added. “And he wants to solidify the relationship with his major backer for what now looks like a long war.”

Mike Eckel reported from Prague; Todd Prince reported from Washington, D.C.

- Mike Eckel is a senior correspondent reporting on political and economic developments in Russia, Ukraine, and around the former Soviet Union, as well as news involving cybercrime and espionage. He’s reported on the ground on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the wars in Chechnya and Georgia, and the 2004 Beslan hostage crisis, as well as the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

- Todd Prince is a senior correspondent for RFE/RL based in Washington, D.C. He lived in Russia from 1999 to 2016, working as a reporter for Bloomberg News and an investment adviser for Merrill Lynch. He has traveled extensively around Russia, Ukraine, and Central Asia.