Regime Change In The Arab World: An Islamic Domino Theory

By INEGMA

By Dr. Paul Cole*

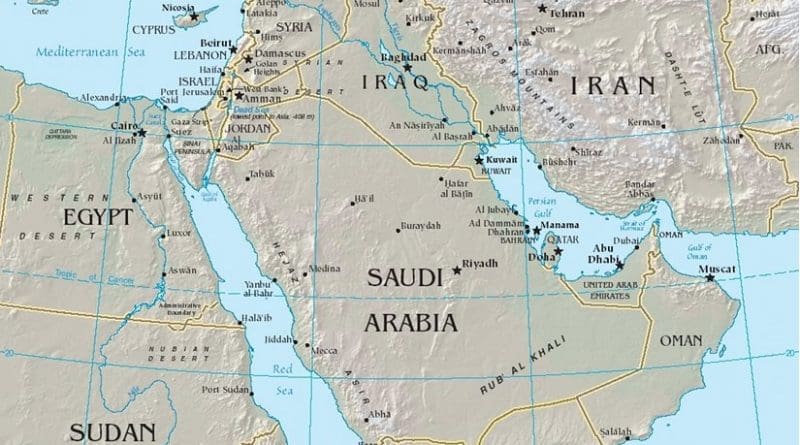

During the Cold War, western security policy was shaped, in some cases decisively, by the Domino Theory, which stated that if one country fell under communist control, all of that country’s neighbors were threatened with the same fate. Recent events in the Arab world suggest that there is an Islamic variation of the Domino Theory. If one country overturns an autocracy, then all of autocratic neighbors of that country may follow suit.

The internal story unfolding in each Arab country undergoing regime change, though extremely important, should not divert attention from a question of equal, if not greater importance. What are the implications of regime change in the Arab world for the future of the international system?

Is Conflict Permanent?

After the 1980 U.S. presidential election, outgoing Carter national security officials briefed President-elect Reagan. One of the out-going Carter people said to the in-coming Reagan people, “The U.S.-Soviet conflict is a permanent feature of the international political landscape.” President-elect Reagan responded, “Says who?”

Two schools of thought among Washington’s foreign policy glitterati dominated reactions to Reagan’s comment. The entrenched establishment, whose entire professional life was informed by the political structures of the Cold War, immediately concluded that “Ronnie Ray-guns,” as he was known by his many detractors, was a neophyte whose lack of foreign policy experience was at least naïve, if not a threat to world peace.

The acolytes of the incoming president saw things from an entirely different perspective. In their view, the management of threats was a bankrupt policy, both morally as well as intellectually. In their view, the purpose of national security policy was to eliminate threats, not to manage them. The very idea that a threat or conflict had neither counter-measure nor solution was totally anathema to the Reaganites.

Three decades on, the debate among analysts of the Cold War is whether Reagan’s policies ended the U.S.-Soviet competition, or if the 40th U.S. President was merely fortunate to be in the right historical place at the right historical time, when the Soviet Empire imploded under the weight of internal contractions of its own making.

Imagine a similar briefing to an incoming president-elect in 2012. This time, however, the national security briefer asserts, “Conflict between Islam and the West is a permanent feature of the international political landscape.” On what grounds could the legitimacy of this assertion be challenged with the same clarity Reagan used to question the conventional wisdom of his day? Or is the assertion true? Is the conflict between Islam and the West a permanent feature of international politics?

Jaw-Jaw or War-War?

During the Cold War, the only place where U.S. and Soviet forces fought one another openly was in the sphere of political rhetoric. Both sides engaged in hostile rhetoric, while the majority of fighting was delegated to allies and proxies. Episodes of direct fighting, between small forces or battlefield advisors, can be counted on two hands. This type of conflict was kept secret from the general public. The threat of large scale conflict between the two blocks was so remote that only two serious episodes, the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) and the Soviet nuclear alert in 1983, occurred over a period of four decades.

Over time, conflict between the two blocks became institutionalized, with codified rituals rarely violated by either side. The rules of the Cold War precluded a declaration of war. The irreconcilable nature of the underlying belief systems clearly indicated that the two were mutually exclusive, thus an open declaration would have merely stated the obvious. Both systems taught that each would triumph over the other, with or without a declaration of war. George Orwell, who invented the term “Cold War,” perceived a world in which there was a “peace that was no peace” between “horribly stable slave empires.” On both sides, the Cold War was understood to be a fight to the finish.

Political culture within the Sino-Soviet bloc was held together by the orthodoxy of first Marxist-Leninism, then by its variations and deviations. No other form of political discourse was admissible. From the perspective of the dialectical materialist, the dictatorship of the proletariat was inevitable. The conduct of the competing system, which was doomed by the forces of history, followed a pre-ordained script. The phrase, “No other value system is so wholly irreconcilable with ours,” which featured prominently in NSC-68 (1950), could have been written by any number of Marxist theoreticians about the capitalist system.

Americans, on the other hand, devoted an inordinate amount of effort and national treasure to the dark art of Kremlinology. Interpretations of Soviet policy, discerned from scraps of information, were presented as answers to vital questions. Was the USSR expansionist? Was the Bolshevik foreign policy agenda fundamentally different from that of imperial Russia? Thousands of American academics and public servants spent their entire career pondering what, in retrospect, appear to be rather trivial issues, rather than what at the time were believed to be the indices of apocalyptic reckoning.

Over time, the two blocks became locked in a mutually-reinforcing pattern of interaction that bordered on inter-dependence. There is no telling how long the Cold War would have continued had the USSR managed its finances more effectively. One of the enduring lessons of the Cold War is that communist governments could fake anything, except the economy.

Looking back, one can clearly see that when the Cold War became a reality in 1948, no one had an inkling that it would become a semi-permanent feature of the international political landscape for fifty years, any more than Wallenstein or Gustavus Adolphus knew in 1638 that they were engaged in a Thirty Years War.

How Long?

Today, more than two decades following the collapse of the Soviet empire, the West is again confronted by an adversarial ideology, this time deriving from Islam, its variants (and deviations). Americans who struggled to distinguish between Marxists and Leninists are faced with an adversary whose variations, such as Sunni, Sufi, Shiite and others, are just as complex.

For the sake of argument, assume that there is such a thing as Monolithic Islam, although it, like Monolithic Communism, is more of an intellectual crutch than a meaningful expression of international politics. While it is early days in the modern manifestation of the conflict between the West and Monolithic Islam, a form of idealized conflict, much like that of the Cold War era, has been established. Inchoate rules of engagement, which are generally understood by both sides, encompass ideology, culture and military competition.

During the Cold War, radical intelligentsia in the West found common cause with the Communist bloc. The construction of the Berlin Wall demonstrated once and for all that the communist system in Europe lacked all legitimacy. Khrushchev’s 1956 speech denounced the depravities of Stalinism, yet even so, the despots who operated under the banner of Marxist-Leninism managed to cling to power for another four decades.

A similar strain of moral equivalency in the West, while not going as far as to find common cause, has become an apologist for the anti-intellectualism and misogyny of some variants of Islam. One of the ironies of history is that the people of the various Arab states are rejecting the social straightjacket of theocracy faster than the western apologists can find reasons to warn against the unpredictable nature of democracy in the Arab world.

From Here to Eternity, Or Not

We know now that the U.S.-Soviet competition, in fact, was not a permanent feature of the international system. Protestors in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain and Iran are not burning U.S. flags, or denouncing western imperialism.

The professionals in East Germany hardest hit by the fall of the Berlin Wall were those whose expertise consisted of teaching the doctrine of Marxist-Leninism. The end of the Cold War left them without a job.

It would appear, based on recent events, that the confrontation between Islamic and western nations is not a permanent feature of international politics. If this is true, the demand for Islamic extremists should be expected to decline as well.

Dr. Paul Cole, Non-Resident Scholar, INEGMA