Is A Monster UBS Bank Bad For Switzerland? – Analysis

By SwissInfo

The dramatic takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS has concentrated all the risk of the rescue onto the shoulders of one Swiss bank. That makes some people in Switzerland very nervous.

By Matthew Allen

The Swiss government seems determined to see the CHF3 billion ($3.25 billion) takeover completed by the end of this year despite considerable opposition brewing in parliament.

“Switzerland is too small for such giant banks. We must find a way to minimise the risk,” Social Democratic Party president Cédric Wermuth told Swiss public broadcaster SRF.

Various political parties present different arguments but many agree that the Swiss retail operations of Credit Suisse should be separated and made safe.

“It strikes me as odd that the people in charge of driving the merger did not seem aware that this solution would be politically unacceptable in Switzerland,” Klaus Wellershoff, founder of his eponymous financial consultancy firm, told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Wellershoff, who was once UBS chief economist, predicts a rocky ride for his former employer. “It is not advisable for any type of operation of systemic relevance to be at loggerheads with 80% of political parties,” he said.

One school of thought is that risk could have been diversified by breaking up Credit Suisse and selling various parts to financial companies worldwide.

Rival bids

Despite the frantic, last-ditch scramble to save Credit Suisse from a completely uncontrolled collapse, it appears that other options did exist.

The Financial Times has detailed a rival bid put together by United States firm Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager.

One Swiss financial consultancy, which did not want to be named, told SWI swissinfo.ch it had been approached by two European banks looking to buy Credit Suisse in the weeks leading up to the collapse.

Keeping the Credit Suisse solution within Switzerland has given the government more control over the process and minimized the inevitable delays of requiring detailed input from other countries.

But Arturo Bris, professor of finance at Switzerland’s prestigious IMD business school, believes the UBS deal was still forced through under international duress.

“Switzerland was under pressure from US, European and British regulators to clean up this mess before markets opened on Monday morning [March 20],” he said. “Switzerland should not have submitted to that pressure.”

“When [US bank] Lehman Brothers went bankrupt [in 2008], the US regulators couldn’t care less about creating a crisis for the rest of the world. The Swiss care too much. The government should have resolved this for the benefit of the Swiss people.”

Ticking time bombs

Switzerland’s second largest bank is terminally ill but currently ticks over on the life support offered by emergency credit lines from the Swiss National Bank.

The ailing patient contains many healthy organs: a network of retail branches, billions in Swiss deposits and loans and a still viable wealth management unit.

Years of mismanagement, however, have infused Credit Suisse with toxins, most notably sour investment banking trades and a host of legal issues.

Instead of ripping out the ticking time bombs and throwing them into the global oceans, Swiss bank UBS has been forced to swallow everything whole.

UBS chair Colm Kelleher painted an optimistic picture, saying the takeover presents “enormous opportunities” and that “UBS will remain rock solid.”

Once the merger is complete, UBS will become the undisputed number one for customer deposit and loan volumes in Switzerland.

UBS forecasts it will become the second largest wealth manager in the world (currently fourth) and achieve promotion from the sixth biggest asset manager in Europe to third spot.

“The takeover ensures the stability of the Swiss financial centre,” says the Swiss Bankers Association. Not everyone agrees.

Far too big to fail

The fusion of Switzerland’s two largest banks will transform the financial landscape from a duopoly of ‘too big to fail’ institutions into a single mega-bank.

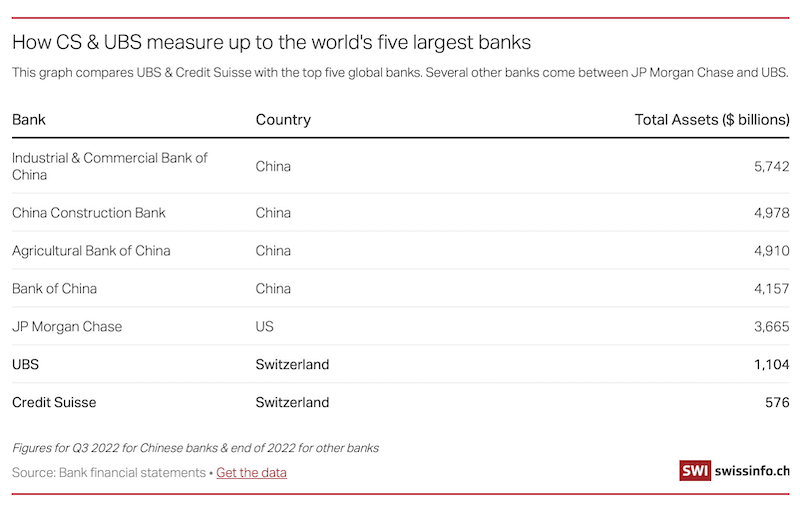

The combined balance sheet of both banks is currently more than twice Switzerland’s CHF800 billion annual economic output.External Content

“After the sale, we will have a financial behemoth in Switzerland,” Marc Chesney, professor of finance at the University of Zurich, told SWI swissinfo.ch in an interview.

“What will happen next time, when it is UBS that is in trouble, like in 2008? Who will buy UBS? A cantonal bank? Where exactly are we going?”

Arturo Bris is concerned that Swiss taxpayers are once again threatened with a large bill for a bank rescue. The Confederation has promised to absorb CHF9 billion of UBS losses should it need to write off bad Credit Suisse investments.

Bris also believes the merger of Credit Suisse and UBS will make retail clients pay in other ways.

“We will be left with a giant bank that will be monopolistic and much more risk averse,” he said. “This is bad for customers.”

“Bank services will become more expensive and UBS’s credit controls will become more stringent. They will issue fewer loans – people who need credit will not get it from UBS.”