Basketball’s ‘Hot Hand’: Myth Or Reality – Analysis

By VoxEU.org

The idea that basketball players can find themselves with a ‘hot hand’ – a streak in which they seem magically to make shot after shot – resonates with sports reporters and spectators alike. This column investigates whether the idea of the ‘hot hand’ holds any basis in fact. Analysing 12 seasons of data from the National Basketball Association, including over 500,0000 free throws and two million field goals, the authors conclude that the basketball ‘hot hand’ is largely illusory.

By Robert Lantis and Erik Nesson*

If a basketball player makes a shot, is he or she more likely to make their next shot? What about if a player makes two, three, or four shots in a row? Many players, coaches, and fans believe the answer is yes, and references to a ‘hot hand’ are common in basketball coverage. During the abbreviated 2019-2020 National Basketball Association (NBA) Season, one reporter described the Houston Rocket’s guard James Harden “enjoying a hot hand” and attributed Orlando Magic guard D.J. Augustin’s standing as a top fantasy free agent to “his recent hot hand” (McCormick 2019a, b). But is the hot hand real or merely a cognitive illusion? This is the question at the heart of the hot hand hypothesis, which has fascinated researchers and sports enthusiasts for 35 years.

Interest in the hot hand began with a 1985 landmark study by Gilovich, Vallone, and Tversky (henceforth GVT), who note in their opening sentences that belief in shooting streaks is widespread: “[R]eporters and spectators commonly use expressions such as ‘Larry Bird has the hot hand’ or ‘Andrew Toney is a streak shooter.’ These phrases express a belief that the performance of a player during a particular period is significantly better than expected on the basis of the player’s overall record.” GVT hypothesise that this widespread belief may be a cognitive illusion and test for the existence of shooting streaks in three settings: NBA field goals, NBA free throws, and a controlled experiment conducted with college players. Failing to find evidence for a hot hand in any setting, GVT conclude that the hot hand is an illusion.

GVT spawned considerable interest in the hot hand across a variety of settings and sports, including baseball (Green and Zwiebel 2018), horseshoe pitching (Smith 2003), tennis (Klaassen and Magnus 2001), and bowling (Dorsey-Palmateer and Smith 2004). Researchers commonly find evidence of a hot hand in these sports. In basketball, recent research largely focuses on controlled settings, like shooting experiments, the NBA 3-point contest, or free throws, and researchers find evidence of a hot hand in these controlled settings as well (Arkes 2010, Miller and Sanjurjo 2018, Miller and Sanjurjo 2019).

Controlled shooting situations versus field goals in games

If the original question at the heart of the hot hand is whether a physiological mechanism exists for success in repeated movement patterns, then the hot hand debate would be largely settled. But the hot hand hypothesis concerns the widely held belief in the hot hand in game situations. In basketball, the setting most relevant for examining those beliefs is field goals in the run of play, not controlled shooting situations.

The relevance of results from controlled shooting situations to field goals is questionable, as field goals are often taken minutes apart, from very different locations, and in different game situations. Across 12 NBA seasons that we study, players’ shots on average are over three and a half minutes apart and are taken nearly 16 feet (4.88 metres) away from each other. But investigating the hot hand in field goals presents additional challenges not faced in controlled settings. For example, previous papers find that a team’s offense and defence both react to previously made shots (Aharoni and Sarig 2012, Attali 2013, Bocskocsky et al. 2014, Bühren and Krabel 2015, Csapo and Raab 2014, Csapo et al. 2015, Rao 2009). Not fully accounting for these endogenous responses may lead to omitted variable bias. Fewer papers examine the hot hand in field goal shooting, and those that do come to varied conclusions (Bocskocsky et al. 2014, Bühren and Krabel 2015, Csapo and Raab 2014, Csapo et al. 2015, Rao 2009). This is unfortunate, as carefully examining the hot hand in field goal shooting is the clearest way to determine whether the widespread belief in the hot hand is correct.

New evidence: The hot hand appears in free throws but not in field goals

In new research (Lantis and Nesson 2019), we attempt to resolve the conflicting accounts from controlled shooting situations, where a hot hand effect is commonly found, and field goal shooting, where the results are inconclusive.

We collect play-by-play data for the 2004-2005 through 2015-2016 NBA regular seasons from http://www.bigdataball.com to examine free throws, a relatively controlled setting, and field goals, which are more relevant to beliefs about the hot hand. Examining both settings with the same players and games allows a more direct comparison of the existence and magnitude of the hot hand effect in more controlled and less controlled settings.

Our 12 seasons of NBA data include over 500,0000 free throws and two million field goals, giving us sufficient statistical power to detect relatively small hot hand effects. We add detailed player and game characteristics from www.basketball-reference.com to account for a large number of game, player, and shot characteristics in our models.

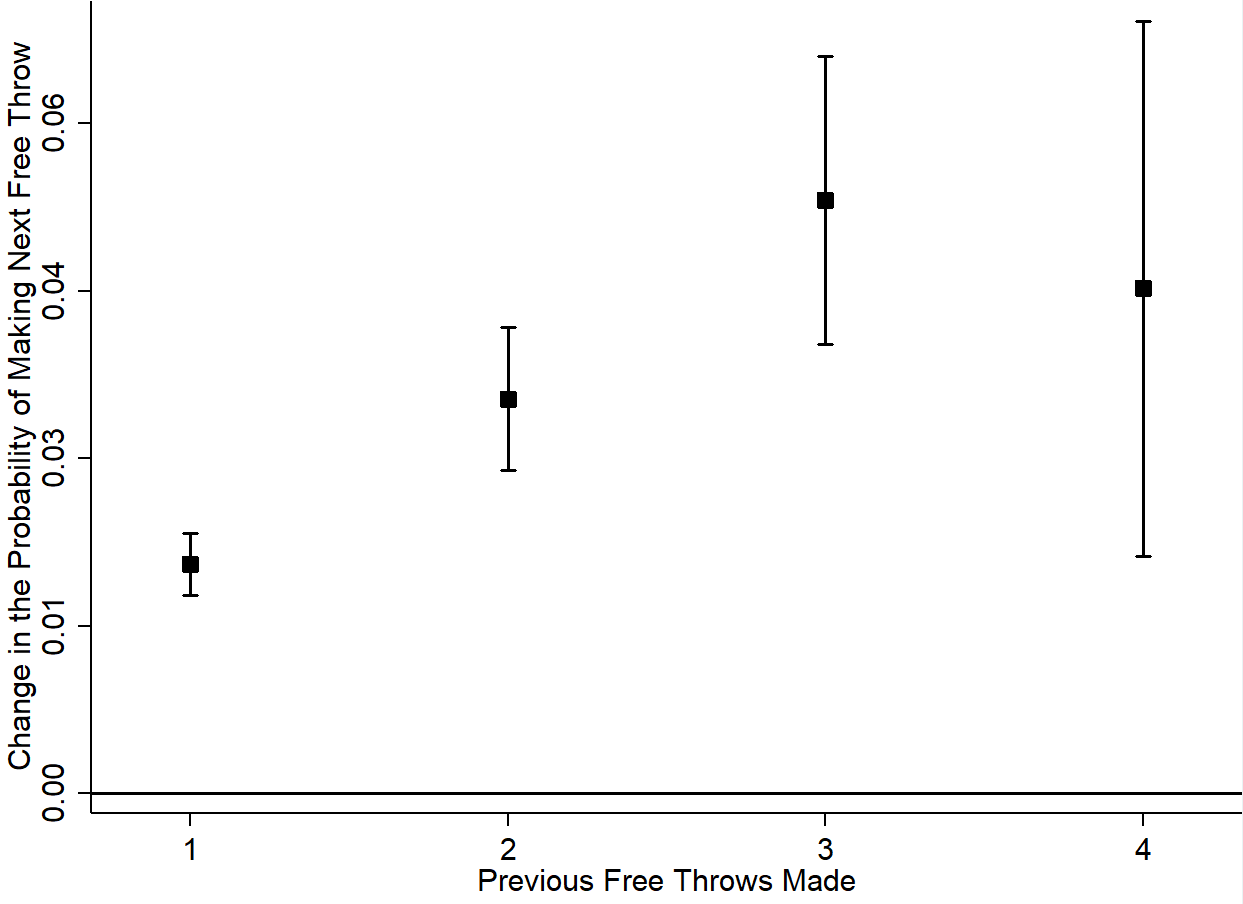

In free throws, we find a consistent hot hand effect, confirming and extending previous findings from Arkes (2010). Figure 1 shows the estimated change in the probability that a player makes his next free throw after different numbers of made free throws in a row, along with the 95% confidence intervals for the estimated change. We find that if a player makes his previous free throw, he is about two percentage points more likely to make his next free throw, and the free throw hot hand effect grows for longer streaks. Making four free throws in a row increases the probability a player makes their current shot by about 4.5 percentage points.

Figure 1 Change in probability of making next free throw after streaks of made free throws

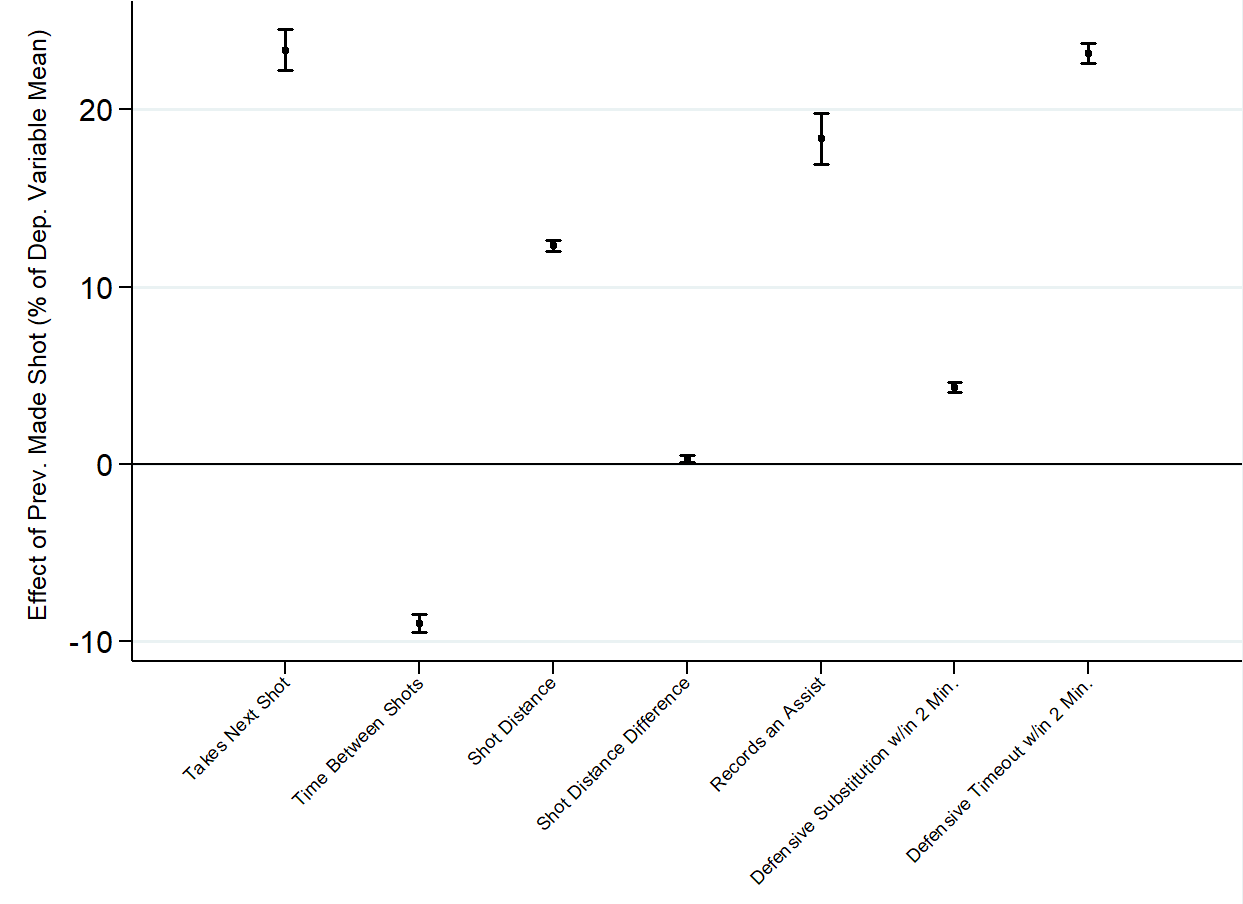

Before we assess whether a hot hand exists for field goals, we examine responses to made field goals. Figure 2 demonstrates that both offenses and defences react to made field goals as if a hot hand effect exists, similar to previous studies (Aharoni and Sarig 2012, Attali 2013, Bocskocsky et al. 2014, Bühren and Krabel 2015, Csapo and Raab 2014, Csapo et al. 2015, Rao 2009). Starting with offensive adjustments, if a player makes his previous field goal attempt, he is about 23% more likely to take his team’s next field goal attempt; the time before he takes his next field goal attempt decreases by almost 10%; he takes his next field goal attempt about 12% further away from the basket (although the distance between shot locations barely changes); and he is 18% more likely to record an assist on the next play. Defences also react to made field goals as if the hot hand effect exists: they are about 4% more likely to make a substitution and 23% more likely to call a timeout within the next two minutes.

Figure 2 Offensive and defensive responses to made field goals

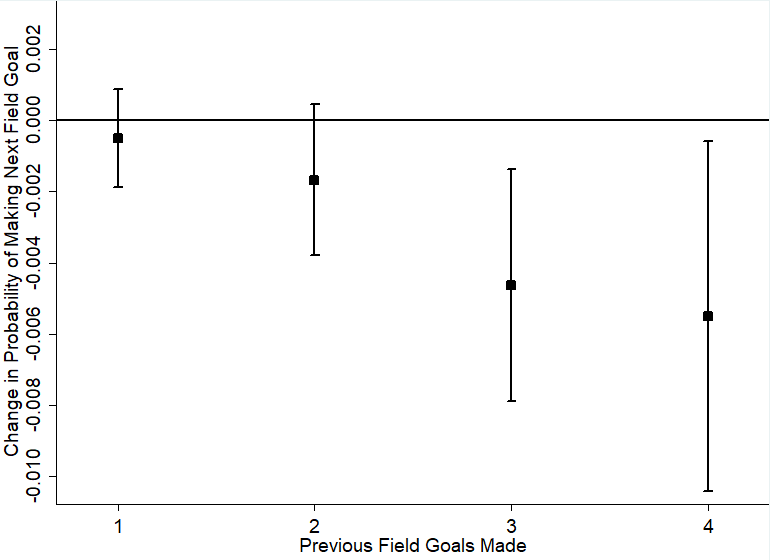

Figure 3 shows the effect of making previous numbers of field goals on the probability that a player makes his next field goal and paints a starkly different picture of the hot hand. We find no relationship between making a previous field goal and the probability that a player makes his next field goal, but as players make longer streaks of shots, the probability of making their next shot decreases. We estimate that if a player makes four field goals in a row, he is 0.6 percentage points less likely to make his next field goal attempt.

Figure 3 Change in probability of making next field goal after streaks of made field goals

So where does this leave the hot hand hypothesis? Our findings are consistent with a hot hand existing due to muscle memory from repeated physical movements. But this muscle memory appears to dissipate quickly or is easily overwhelmed by other factors. Thus, on balance, our results suggest that the original hypothesis posed by GVT is largely correct: there is not a hot hand in the setting where most observers believe one to be.

*About the authors:

- Robert Lantis, Assistant Professor of Economics, Ball State University

- Erik Nesson, Associate Professor of Economics, Ball State University

References

Aharoni, G and O H Sarig (2012), “Hot hands and equilibrium”, Applied Economics 44 (18): 2309-2320.

Arkes, J (2010), “Revisiting the hot hand theory with free throw data in a multivariate framework”, Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports 6 (1).

Attali, Y (2013), “Perceived hotness affects behavior of basketball players and coaches”, Psychological Science 24 (7): 1151-1156.

Bocskocsky, A, J Ezekowitz and C Stein (2014), “Heat check: New evidence on the hot hand in basketball”, Working Paper: 1-30.

Bühren, C and S Krabel (2015), “Individual performance after success and failure: A natural experiment”, Working Paper: 1-22.

Csapo, P, S Avugos, M Raab et al. (2015), “The effect of perceived streakiness on the shot-taking behaviour of basketball players”, European Journal of Sport Science 15(7): 647-654.

Csapo, P and M Raab (2014), “ ‘Hand down, Man down’, analysis of defensive adjustments in response to the hot hand in basketball using novel defense metrics”, PloS One 9 (12): 1-25.

Dorsey-Palmateer, R and G Smith (2004), “Bowlers’ hot hands”, The American Statistician 58 (1): 38-45.

Gilovich, T, R Vallone and A Tversky (1985), “The hot hand in basketball: On the misperception of random sequences”, Cognitive Psychology 17 (3): 295-314.

Green, B and J Zwiebel (2018), “The hot-hand fallacy: Cognitive mistakes or equilibrium adjustments? Evidence from major league baseball”, Management Science 64 (11): 5315-5348.

Klaassen, F J G M and J R Magnus (2001), “Are points in tennis independent and identically distributed? Evidence from a dynamic binary panel data model”, Journal of the American Statistical Association 96 (454): 500-509.

Lantis, R M and E T Nesson (2019), “Hot Shots: An Analysis of the ‘Hot Hand’ in NBA Field Goal and Free Throw Shooting”, NBER Working Paper No. 26510:1-50.

McCormick, J (2019a), “Fantasy NBA Daily Notes: How Harden helps his teammates shine”, ESPN.com, Last Modified December 2, 2019.

McCormick, J (2019b), “Joe Ingles among top fantasy basketball free-agent finds”, ESPN.com, Last Modified December 9, 2019.

Miller, J B and A Sanjurjo (2018), “Surprised by the gambler’s and hot hand fallacies? A truth in the Law of Large Numbers”, Econometrica 86 (6): 2019-2047.

Miller, J B and A Sanjurjo (2019), “Is it a fallacy to believe in the hot hand in the NBA three-point contest?”, Working Paper:1-24.

Rao, J M (2009), “Experts’ perceptions of autocorrelation: The hot hand fallacy among professional basketball players”, Working Paper: 1-25.

Smith, G (2003), “Horseshoe pitchers’ hot hands”, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 10 (3): 753-758.