The Global BLM Movement: Public Memorials And Neo-Decolonization? – Analysis

By RSIS

The toppling of the statue of a slave trader in the UK during the BLM protests raises wider global questions about past “heroes” and their memorials, an issue which has resonances across not just Europe and America but also the globe including Singapore.

By Paul Hedges*

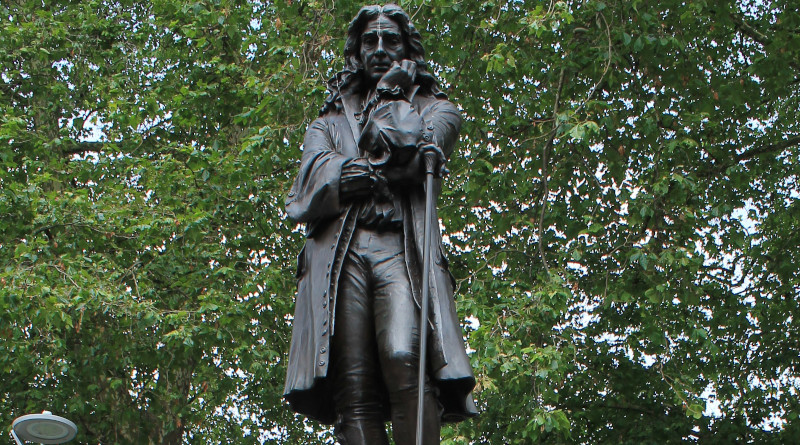

As part of the global Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests, demonstrators in Bristol, United Kingdom, pulled down a statue of a slaver, Edward Colston, and threw it into the river. Police did not intervene, judging it the most appropriate response, no doubt given a peaceful crowd that included families. The atmosphere was one of calm and rational protest, even celebration, not indiscriminate destruction nor anarchy.

Some responses, however, depicted the incident as “thuggery,” violence, and wanton criminality. The British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Home Secretary Priti Patel were strong critics of the action, and have called on the police to prosecute those involved. Yet the Mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees, himself of black African heritage, has spoken about his personal antipathy to the statue and echoed a general sympathy with the action.

Decolonising Public Spaces

The statue has been recovered from the river and is to be placed in Bristol Museum with explanations of slavery’s role in Bristol’s history. Colston’s statue had long been disputed in Bristol, but wider questions about statues and memorials to historical figures whose actions now raise moral quandaries abound.

Started in 2016, a campaign by Oxford University students argued that “Rhodes must fall”), referring to the memorial to southern Africa colonial administrator Cecil Rhodes, which is now likely to come down.

The Belgian government has also, in response to the recent demonstrations, taken down a statue of the infamous King Leopold II who used the Congo as a personal colony and whose brutal regime killed an estimated ten million Africans.

Statues have also fallen in the United States and elsewhere. It has also raised the issue that systemic racism is not just a US issue, but is found in the UK and globally.

Wider Call: Neo-Decolonisation?

This is part of wider calls for a decolonised public space, including museums and other places where “loot” from colonial regimes was deposited. Such decolonisation challenges the way that white colonial (primarily North Western European and North American) regimes of power, knowledge, and control emerged over the last couple of centuries and brutally dominated the globe, including through the British Empire.

The BLM and other movements suggest that the legacy of slavery, looting, and oppression needs to be acknowledged, especially as its legacy in racism and discrimination remain embedded at many layers in society. The monument culture that valorises those deemed “heroes” and exemplars is questioned as it validates many whose work directly embedded today’s systems of discrimination.

There are both those who support the removal of such statues and those who believe they should remain. Objections to their removal include such issues as the following:

These people’s behaviour was, perhaps, normal in their time, though reprehensible by today’s standards, so is it unjust to judge them in this way; there are legal and democratic processes for the removal of such statues, and these protest movements are undermining this; it is wrong to erase history by removing statues as we should remember what has happened.

Contesting History

The issue of history and its memory is of particular importance. It does not concern just the past, but the stories we tell ourselves about who we are today. Against complaints that the BLM campaigners want to erase history, their attitude shows that they take history very seriously.

A few weeks ago, outside of Bristol, almost no one knew who Colston was, but today his legacy is on many people’s lips; and, if transferred to a museum, his memory will have a strong lasting local effect.

Importantly, his statue, like those of others, are not simply a pristine history which has been passed on. Colston’s statue was erected around a hundred years after he died, when Bristol’s ruling classes were seeking a local paradigm of paternalistic philanthropy (he had endowed schools and other institutions in the city) in a particular social context.

History was deliberately made when Colston’s statue was erected, and recent attempts to place another plaque on the statue with differing narratives show disputes about narrating this history. The act of removing it is, in these terms, another act of making history. In this case, recognising the hurt, especially of those of black African heritage, who see slavers valorised in their city.

It is a symbol that Bristol’s wealth, today unequally shared between ethnic groups, belongs to systems of oppression that are still held up as exemplars. It is about how we tell history, not what history is.

With this act, and the mayor’s plan to place Colston in the local museum, we arguably see a far more powerful way of telling Bristol’s history and its contemporary resonances. It is not to say that every statue people object to can simply be pulled down by whosoever wishes. But, there, the act has arguably demonstrated an aspect of the political implications and social contestation inherent within public memorialisation.

The Statue of Raffles

Singapore has not been spared from controversy surrounding the contested history of colonialism. As a former British colony, its colonial legacy has been epitomised in various forms. One of them is the erection of the statue of Stamford Raffles, the architect of British colonialism of Singapore, on the bank of Singapore River, the location where he landed in 1819.

The current statue was erected by the Singapore government to mark 150 years since his landing. His legacy in the Malay Archipelagic region is much disputed, including his significance and connections to the East India Company, and some marginal voices would like to remove the statue.

There was debate as to whether 2019 should have been celebrated as the bicentennial founding of (modern) Singapore by Raffles. Opponents questioned both the appropriateness of celebrating the colonialisation of their country, and also pointed to a much older history going back to the founding of the Malay kingdom of Singapura by Sang Nila Utama in 1299.

Conversely, others felt that the coloniser’s legacy was key to what has become modern Singapore and so had to be acknowledged. The state appreciated both views and finally decided to hold celebrations for a bicentennial that clearly acknowledged the arrival of the earlier inhabitants of Singapore centuries before the coming of the British colonialist.

The matter was therefore resolved for the moment, not with the felling of the statue of Raffles, but with what is seen by many as an amicable and holistic celebration of the country’s early history. However, future Singaporeans may still ask whither Raffles?

*Paul Hedges is Associate Professor in Interreligious Studies with the Studies in Inter-Religious Relations in Plural Societies (SRP) Programme, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.