Soundousse Belayachi: An Artist Who Glorifies Amazigh Women In Her Paintings – Analysis

Art and cultural identity

In all cultures around the world, artistic expression has emerged to provide an outlet for thoughts, feelings, traditions and beliefs. Art can be both rooted in history and can be a catalyst for change in a culture.

Art has long been closely linked to cultural identity, providing a powerful means of expressing, preserving and celebrating diverse cultures around the world. It has the ability to transcend language barriers, bridge gaps between different communities and foster deeper understanding. It goes without saying that art plays a vital role in the formation of cultural identity, without forgetting, however, that it celebrates diversity through creativity. (1)

The salient aspects of the importance of art in any civilization are as follows:

Cultural identity: The unique combination of beliefs, values, traditions, and artistic expressions that define a particular group or community.

Artistic expression: the use of various art forms, such as visual arts, music, dance, literature, and theater, to communicate cultural narratives and perspectives.

Cultural preservation: act of safeguarding and promoting cultural heritage through artistic practices and activities.

Throughout history, art has played a central role in the formation and preservation of cultural identity. From ancient cave paintings to religious artwork, cultural objects reflect the beliefs, customs and aesthetics of different societies.

Art has been a means of telling stories, transmitting ancestral knowledge (2) and asserting cultural pride. In various regions of the world, indigenous art forms have contributed to the resilience and continuity of cultural identities. (3)

Today, art continues to evolve as a reflection of cultural diversity and social dynamics. Artists from diverse backgrounds draw inspiration from their heritage, infusing their creations with personal narratives and cultural symbolism. Contemporary art movements, such as multicultural art, Afrofuturism, and diasporic art, challenge traditional boundaries and explore new dimensions of cultural identity. Museums, galleries and cultural institutions strive to present diverse works of art and create spaces for intercultural dialogue. (4)

Many studies have highlighted the positive impact of art on cultural identity. Research has shown that exposure to diverse artistic expressions promotes empathy, cross-cultural understanding and a sense of belonging. Art-based interventions have been used to address cultural trauma, promote social cohesion, and empower marginalized communities. Data suggests that art plays a crucial role in forming collective memory, building resilience, and maintaining cultural practices. (5)

Traditional Amazigh art

Traditional Berber or Amazigh arts reflect their diverse histories and cultures. Although each group practices slightly different arts, many share several major traditions. A common element is the representation of geometric or natural images on human and animal forms. The Amazighs are also famous for their textiles and weaving. Carpets, in particular, remain an important industry in rural areas. (6)

In many cases, arts and crafts in Berber communities are the domain of women. Women produce rugs, fabrics, clothing, ceramics and baskets.

Berber ceramics tend to be characterized by muted colors decorated with darker symbols and images. Men can produce commercial ceramics and work gold, silver, other metals and precious stones to make jewelry. (7) In previous centuries, some Amazigh cultures practiced tattooing women. The women of the family tattooed the faces and arms of girls as they entered into womanhood. This marked their new adult status and protected them from harmful spiritual forces. However, due to conflicts with Islam, tattooing is no longer practiced in most places. (8)

On the nature of Amazigh art, Hajar Ouahbi writes: (9)

“Culture is an aggregation of the various sources that underpin the identity of a person, a people, or a state. Art is often a powerful medium to highlight these different sources, from their starting points to their endpoints. Bringing these cultures to light is all the more of a challenge when it comes to Amazigh culture. As an essentially oral culture, its bearers must be able to convey its versatility without compromising their preferred artistic fields.”

Amazigh rock art

The Sahara is the world’s largest non-polar desert, covering nearly 8,600,000 km² and including most of North Africa, from the Red Sea to the Atlantic Ocean. Although considered a distinct entity, it is composed of a variety of regions and geographic environments, including sand seas, hammadas (stone deserts), seasonal waterways, oases, mountain ranges and rocky plains.

Rock art is present throughout this region, mainly in the mountain ranges and desert hills, where stone “webs” are abundant: the Adrar highlands in Mauritania and the Adrar des Ifoghas in Mali, the Atlas Mountains in Morocco (10), Tassili n’Ajjer and Ahaggar in Algeria, the mountainous areas of Tadrart Acacus and Messak in Libya, (11) the Aïr mountains in Nigeria, the Ennedi plateau and the Tibesti mountains in Chad, the Gilf Kebir plateau in Egypt and Sudan, as well as along the Nile. (12)

Although the styles and subjects of Amazigh rock art vary, there are commonalities: the images are most often figurative and frequently depict wild and domestic animals. There are also many images of human figures, sometimes accompanied by props such as weapons or recognizable clothing. These may be painted or engraved, both being common, sometimes in the same context. Engravings are generally more common, although this may simply be preservation bias due to their greater durability.

The physical context of rock art sites varies depending on geographic and topographical factors – for example, Moroccan rock carvings are often found on open rock outcrops, while the Djebibina rock art sites in Tunisia have all been discovered in rock shelters. Rock art in the vast and hostile environments of the Sahara (13) is often inaccessible and difficult to find, and there is likely much rock art that has not yet been seen by archaeologists; what is known has mostly been documented over the last century.

Soundousse, who are you?

Soundousse was born in Casablanca in 1971. She did her primary studies at the Jean Jaurès and Victor Hugo School and secondary studies at the Lycée Lyautey IV. From a young age she had a weakness for drawing, painting and sport. She drew on everything that came to hand: white sheet, newspaper or even fabrics and walls.

In 1995 she married and settled in Rabat and had 2 children: a daughter Sourour, currently a financial analyst in London and Faris a computer engineer in Paris. Between 2000 and 2002 she moved to Paris for her children’s studies. In 2012, she returned to Paris where she began studying art at the prestigious Fleurimon Paris school. So, she prepared a higher diploma in make-up and artistic hairstyling for cinema, theater, television, fashion shoots and advertising.

With her diploma in hand, she returned to Morocco in 2014 and began a career as a painter, artist and interior decorator and artistic decoration consultant.

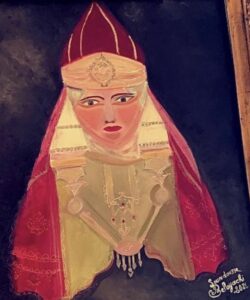

Her painting focuses on women in Moroccan daily life. Being of Amazigh origin, for Soundousse, women are the pillar of Moroccan society and the undisputed soft power of its ancient culture. Indeed, for her, the Amazigh woman is the indisputable master of the arts of weaving, tattooing and pottery which make Amazigh art a rich and millennial cultural heritage.

On the relevance of Amazigh tattoos, Sahar El Faijah writes: (14)

“Amazigh tattoo has been admired for its beauty across the whole world. However, reductions to such an asset fail to address its complexity and ignore its associated importance. Indeed, Amazigh tattoo system is not merely a crucial societal aspect, but a proper visual language. Frequently and mistakenly associated with Arabs, Imazighen are one of the oldest Indigenous civilisations, inhabiting a vast territory mostly covering parts of North and West Africa. Despite various invasions, Amazigh tribes have claimed their distinct identities and have preserved their culture. [1] Women have always occupied a central position on multiple societal levels and upheld the Amazigh cosmology. [2] A remarkable key role has included the safeguarding of traditions and customs, through art such as music and poetry; but also through a rich repertoire of visual signs, often recaptured in crafts such as pottery.”

Amazigh women and art

For Soundousse, in a sense, women create their own power. Most importantly, women are the artists of Berber culture. Berber women express their art in carpet weaving, textile making, body tattoos, and decoration of the face, hands, and feet. (15)

These feminine practices have been going on for millennia. We know that visual expression long predates any form of written recording. The shapes, colors and meanings of Berber women’s artistic expressions tell powerful stories. Women dominate the weaving process, metaphorically bringing textiles to life. In rural areas, they paint, spin and dye wool to make blankets, shawls and rugs which they weave on vertical looms. (16)

It is believed that the wool is imbued with considerable baraka (blessing), and that part of this baraka would be transferred to the weavers, hence the sacred nature of the weaving. Berber women who work with wool are very respected and it is said that a woman who makes 40 carpets during her life is guaranteed access to paradise after her death. (17)

This art is a source of pride and self-confidence for the next generation. It ensures continuity and promotes common values of family, support, business, etc. Political will and technology (the satellite dish and the Internet) help the carpets survive. (18)

Women are valued as guardians of Berber language and culture and play a central role in constructing identity. The construction and preservation of identity through art are also at the heart of the religious and spiritual action of Berber women. (19)

For Soundousse, Amazigh women reveal their artistic talents in several ways:

”Through their artistic expressions, women not only control marriages as a means of preserving the sanctity of cultural particularities amid powerful societal influences, such as modernization, which are rapidly affecting their lives, but they also weave rugs, make tents and pottery, decorate the face, hands and feet with henna and embroider clothing that reinforces Berber ethnic identity. Through art and mother-daughter transmission, Berber women connect the past to the present.”

This link gives a material form to Amazigh consciousness. Berber women demonstrate the esteem, respect and status accorded to motherhood by incorporating fertility symbols into their rugs, clothing, tattoos and hairstyles. Amazigh arts are therefore metaphors for motherhood, demonstrating the crucial role that women play in the propagation and preservation of Amazigh identity.

There has also been a re-emergence of Amazigh women’s symbolism in contemporary youth culture. This can be seen in the names of various women’s centers: Tanit, Isis, Kahina, etc. Likewise, various groups, websites, fashion shows, and clothing styles popular among young people have the same names.

Although largely absent from formal historical accounts, the rituality, orality and art of Amazigh women constitute a veritable source of knowledge, challenging traditional narratives about women’s roles in production, use and adaptation of knowledge.

Amazigh women and their artistic soul: expressions of identity

For Soundousse Belayachi one of the reasons why Amazigh women are artists is that the arts are expressions of ethnic identity, and it follows that the guardians of Amazigh identity should be those who literally ensure its continuation from generation to generation. It is not surprising that the arts are visual expressions of femininity and that fertility symbols are prevalent. Control of the visual symbols of Amazigh identity gave these women power and prestige.

Soundousse goes on to say that their clothes, tattoos and jewelry are public statements of identity; such public artistic expressions contrast with the stereotype that women in the Islamic world are isolated and veiled. But their role as symbols of public identity can also be restrictive, and recent history has forced women to adapt their arts as symbols of public identity.

As such, Soundousse emphasizes that:

“Amazigh women perpetuate their traditional culture through carpet weaving, and they are both valued and marginalized within their society. The need and pressure on them lead to issues related to gender equality and girls’ rights/accessibility to quality education in the modern context. Although constantly evolving and changing over time, the nomadic lifestyle and traditional Berber rug weaving are still present today and nevertheless hold deep meaning for those who participate in these activities. Traditional mindsets regarding gender norms remain intact, although they are more frequently challenged. Women’s weavings are essential to the preservation of Amazigh culture and openly symbolize a heritage identity, placing women at the heart of Berber history and heritage.”

Empowerment of Amazigh women

Soundousse says Amazigh women in Morocco traditionally suffer from triple marginalization: as women, indigenous and rural. The language and geography of the Atlas and Rif mountains where they live also make it difficult for them to access the most basic educational and health resources. This is why Amazigh women are often represented in many studies as “illiterate” and “in need of help”. But a careful examination of the history and daily reality of Amazigh women reveals another facet of their story that still remains to be told and on which I shed light in my paintings: beauty, courage and resilience. I focus on the agency and resilience of Amazigh women and how they transform their daily reality and vulnerabilities into opportunities that empower them, their families and their communities. (20)

In addition, Soundousse strongly argues that:

”Through their knowledge and practices, Amazigh women contribute as active agents of civil society, caring not only for the well-being of their own families, but also for the development of their community and the heritage of their culture. Clear examples can be provided of how these women contribute to the local economy and rural development by organizing and working in cooperatives dedicated to carpet weaving, argan oil production and the arts. artisanal. Culture and tradition, recovered and preserved by women, emerge as a source of recognition of Amazigh identity, development of local communities and empowerment of women.”

Amazigh women leaders

Among the Amazigh women leaders, we can count:

Dihiya, which means the beautiful gazelle. She was born at the beginning of the 7th century in the Aurès mountains in Algeria. According to Ibn Khaldun, among their most powerful leaders of the Amazigh, there was a woman, queen of Mount Auras, whose real name is Dihiya, daughter of Tabeta, son of Tifan. Her family was part of the Djeraoua, who paid homage to the kings and chiefs of all the Berbers that descended from El-Abter. She is also known in Arabic as al-Kahina, meaning prophetess, seer or witch, a title given to her by Muslim opponents because of her alleged ability to foresee the future. The warrior queen Dihiya played an important role in defending her kingdom and leading the North African resistance against the early Arab-Islamic conquests of the Maghreb, the region then known as Numidia. (21)

Tanit was considered the goddess of prosperity, fertility, love and the moon in Carthage. The female goddess had a balanced presence in the religious conception of the ancient peoples of the Amazigh of North Africa.

Tin Hinan, meaning that of the tents, is thus designated this Tuareg princess by the Amazighs of the Azawad and the surrounding regions of Mali, Nigeria, Libya and Algeria. Tin Hanan always played a leading role in the protection of the Tuareg tribes because she was revered and respected as a symbol of balance and social, political and spiritual stability. The Tuareg tribes considered her their spiritual mother. (22)

Ralla Bouya of the Tamsaman tribe is a warrior queen, a saint among the Rifis of the 19th century apparently. Her image today in the Rif is a mixture of historical facts and heroic myths transmitted over time. No renowned Rifi poem (izri) would fail to mention Ralla Bouya, and no prayer, oath or word of honor is pronounced without invoking her name. (23)

Conclusion: Arts of Amazigh women, visual expressions of Berber identity

Until today, Berber women in North Africa create and wear the aesthetic and symbolic forms that make the Amazigh identity unique. Women wear silver, amber and coral jewelry, which proclaims their status, wealth and group membership. (24) They incorporated symbols and colors related to female fertility into their textiles, clothing, tattoos, and hairstyles as expressions of feminine agency. Despite societal influences that have changed daily life, women continue to produce and use ancestral artistic forms, particularly during rural weddings, demonstrating the crucial role that women continue to play in preserving Amazigh heritage. (25)

Soundousse Belayachi’s paintings celebrate these Amazigh women in their proverbial beauty but also in the purity of their adornments, their fibulae, their jewelry and their clothing and in their coquetry.

For Soundousse, the Amazigh woman creates around her a world of natural beauty, magic but also surrealism through which she expresses in a strong way her centuries-old cultural identity, knowing full well that the Amazigh women of the Rif, the Atlas, the Sahara have been fighting, for ages, the denial of their cultural identity through art: painting, jewelry, clothing, pottery, tattooing, dancing, singing, etc.

In this regard, Soundousse points out that:

“The practice of carpet-weaving dates back almost 2,200 years and is believed to have originated in rural communities in the Middle Atlas Mountains and around Marrakech. At that time, these populations were nomadic. The women therefore took advantage of each stopover to make fabric for mattresses and blankets, with the wool of the animals from their flock, sheep or goats. Proud of their freedom, these artisans have never used a model. They weaved according to their own inspiration, making each rug a unique creation.’’

And she goes on to say:

”Berber women weave brightly-colored rugs, embroider indigo headdresses, paint their faces with saffron and wear ornate jewelry. Their extraordinarily detailed art is rich in cultural symbolism; they are always breathtakingly beautiful.”

One of the reasons why Amazigh women are artists is that the arts are expressions of their ethnic identity, and it follows that because they are the guardians of the Amazigh identity, they endeavor to ensure its continuation from generation to generation. It is not surprising, as well, that their arts are visual expressions of their femininity. (26)

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter/X: @Ayurinu

Endnotes:

- Servier, J. (2017). Chapitre VI – L’art berbère. Dans : Jean Servier éd., Les Berbères (pp. 112-119). Paris cedex 14: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Michel Barbaza, Michel. (2012). Les gravures rupestres libyco-berbères : d’une rive à l’autre du Sahara. Palethnologie, 4. http://journals.openedition.org/palethnologie/6068; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/palethnologie.6068

- Hwa Young Choi Caruso. (2005). Art as a Political Act: Expression of Cultural Identity, Self-Identity, and Gender by Suk Nam Yun and Yong Soon Min. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 39(3), 71-87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3527433

- Bravin, A. (2009). Les gravures rupestres libyco-berbères de la région de Tiznit (Maroc). Paris : L’Harmattan.

- Hachid M. (2001). Les premiers Berbères entre Méditerranée, Tassili et Nil. Aix-en-Provence, Ina-Yas : Édisud.

- Becker, Cynthia. (2006). Amazigh Arts in Morocco Women Shaping Berber Identity. Austin, TX : University of Texas Press.

- Rabaté, Marie-Rose. (2015). Les Bijoux du Maroc : du Haut-Atlas à la vallée du Draa. Courbevoie : ACR Édition.

- Fany. (2021). Culture, traditions et tatouages berbères dans la décoration d’intérieur. https://www.fany-store.com/blogs/magazine/la-culture-tradition-et-tatouages-berberes-dans-la-decoration-d-interieur?customer_posted=true#newsletter-newsletter-popup

- Ouahbi, Hajar. (2020). Amazigh culture through hybrid and futuristic art (R=Translated by Yasmine B.). Dune Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.dunemagazine.net/eng-trans/amazigh-culture-through-hybrid-and-futuristic-art

- Rodrigue, A. (1999). L’art rupestre du Haut Atlas Marocain. Paris : L’Harmattan.

- Rodrigue, A. (1999). L’art rupestre du Haut Atlas Marocain. Paris : L’Harmattan.

- Soukopova, J. (2012). Round Heads: The Earliest Rock Paintings in the Sahara. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Riemer, H. (2013). Dating the rock art of Wadi Sura, in Wadi Sura – The Cave of Beasts. R. Kuper (ed). Africa Praehistorica 26 (pp. 38-39). Köln: Heinrich-Barth-Institut.

- El Faijah, Sahar. (2023). Amazigh Tattoo as a Visual Language. Dune Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.dunemagazine.net/articles/amazigh-tattoo-as-a-visual-language

- Yacine, T. (2001). Women, Their Space and Creativity in Berber Society. Race, Gender & Class, 8(3), 102-113. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41674985

- El Azhar, Samir. (2019). The Changing Roles of Female Visual Artists in Morocco. Academia. Edu. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/73270750/The_Changing_Roles_of_Female_Visual_Artists_in_Morocco

- Bernasek, L. (2008). Artistry of the everyday: beauty and craftsmanship in Berber art (Vol. 2). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Chtatou, Mohamed. (2020). Le tapis amazigh: identité, création, art et histoire. Le Monde Amazigh. https://amadalamazigh.press.ma/fr/le-tapis-amazigh-identite-creation-art-et-histoire/

- Chtatou, Mohamed. (2022). Amazigh women, guardians of language and culture. FUNCI. Retrieved from https://funci.org/amazigh-women-the-genuine-guardians-of-language-and-culture-in-morocco/?lang=en

- Chtatou, Mohamed. (2022). La femme, reine incontestable du monde amazigh. Le Monde Amazigh. https://amadalamazigh.press.ma/fr/la-femme-reine-incontestable-du-monde-amazigh/

- Chtatou, Mohamed. (2021). Al-Kahina, une reine amazighe stigmatisée par les Arabes. Le Monde Amazigh. https://amadalamazigh.press.ma/fr/al-kahina-une-reine-amazighe-stigmatisee-par-les-arabes/

- Chtatou, Mohamed. (2023). Les Touaregs d’Azawad, un peuple amazigh opprimé. Le Monde Amazigh. https://amadalamazigh.press.ma/fr/les-touaregs-dazawad-un-peuple-amazigh-opprime/

- Chtatou, Mohamed. (2024). Tarifit et son rôle primordial dans la culture amazighe du nord du Maroc. Article qui sera publié ultérieurement par L’Université Abdelmalek Essaâdi de Tétouan

- Sadiqi, F. (2008). [Review of Amazigh Arts in Morocco: Women Shaping Berber Identity, by C. J. Becker]. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 41(3), 585-588. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40282533

- Becker, C. (2006). Seven. Contemporary Amazigh Arts: Giving Material Form to Amazigh Consciousness. In Amazigh Arts in Morocco: Women Shaping Berber Identity (pp. 177-194). New York, USA: University of Texas Press. https://doi.org/10.7560/712959-010

- Harries, J. (1973). Pattern and Choice in Berber Weaving and Poetry. Research in African Literatures, 4(2), 141-153. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3818891