Various Views For The 9th Of Av – OpEd

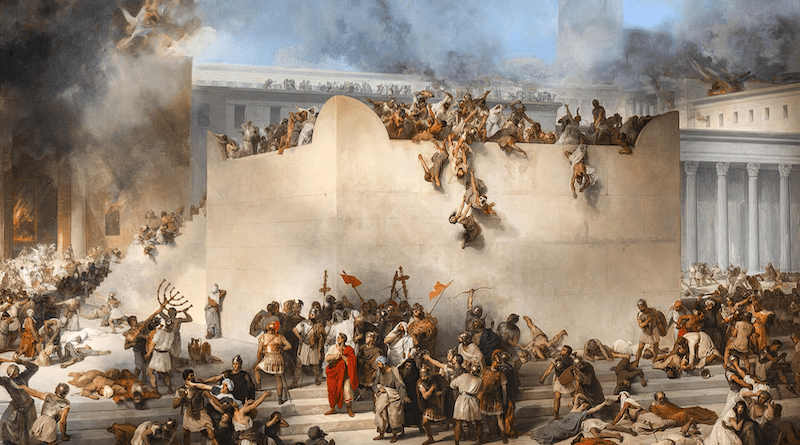

On July 27, 2023 (the 9 day of the Jewish month of Av) Jews in Israel and throughout the world will remember the two destructions of Jerusalem and its Temple on the same day in 587 BCE and much later in 70 CE. This year the political crises within the State of Israel makes understanding the 9th of Av more important than ever.

A special day to commemorate the Holocaust-Shoah was opposed by most Ultra-Orthodox Rabbis who claimed that Jews already had a day for mourning the great tragedies that befell the Jewish people on the 9th day of Av: Tishah B’Av.

The majority of Jews however, felt that the Shoah-Holocaust was different, not only in size and scope, but also in its meaning. The Orthodox view of Tishah B’Av, expressed in an Orthodox prayer book of the holidays, declares that: “because of our sins we were exiled from our homeland.” This could have applied to the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E. and again in 70 C.E., but it should not be applied to what happened to Jewish communities living in Europe during World War II.

The Shoah fit much better into the Zionist analysis of the inherent vulnerability of all Jewish communities living as a minority in countries outside of the Land of Israel. The Six-Day War seemed to confirm Zionist ideology, but the decades-long conflict with the Palestinians makes many Jews in Israel today feel more insecure than many Jews in the Diaspora, thus reversing Zionist ideology.

When peace comes to the Middle East someday, many things will change, including how we think and feel about Tishah B’Av. There are few, if any, modern Jews, who feel any loss at all because a hereditary, male only, priesthood no longer offers animals on the sacred altar of a Temple in Jerusalem.

Many rabbis have struggled to make Tishah B’Av relevant to their congregations by including references to terrible events occurring in our own lifetime like Hi- roshima, Cambodia, Rwanda, or even climate change. This reforming of the focus of Tishah B’Av does help make it more relevant, but in the last two decades I have found it useful to use a different approach to Tishah B’Av.

I used to think that Tishah B’Av was a service dedicated to self-centered self pity as shown in the following passages from the midrash: “When punishment occurs Jacob alone experiences it” (Eichah Rabbah 2:7); “Don’t the Gentiles sin? But although they sin, no punishment follows. Israel, however, sinned and was punished” (Eichah Rabbah 1:35); and “In Egypt there were more than 70 peoples, and of them all only Israel was subjected to slavery” (D’varim Rabbah 4:9).

I now think that correctly taught, the annual occurrence of Tishah B’Av has a potential to serve as an occasion for teaching some alternative and lesser-known views of Jewish historical tragedy as valuable lessons for twenty-first cen- tury Jews today.

Midrash Eichah Rabbah is a collection of midrashim that overwhelmingly supports two popular views in Orthodox Judaism. One view is “because of our sins we were exiled from our home- land” (i.e., it was all our fault). The other view is “Ever since the Temple was destroyed there is no day without a curse” (i.e., exile is hell) (Sotah 49a).

But there have always been some dissenting Sages. One especially important Orthodox Jewish belief is that Israel could not have been defeated unless the God of Israel let Israel’s enemies win, in order to punish the Jewish people for its sins. God’s attribute of justice made this inevitable, even though it saddened God.

God tells Israel “Behold what your iniquities caused Me to do: to burn My Temple, destroy My city, exile My children among the nations of the world, and that I should sit solitary” (Eichah Rabbah proem 10, 20). Yet only a few pages away we find an alternative view, “Were it not explicitly stated in Scripture it would be impossible to say such a thing…the Holy One blessed be He, lamented saying, ‘Woe to a king who succeeded in his youth but failed in his old age!'” (Eichah Rabbah proem 14).

This introduces the concept of a God who is weakened when we do not do mitzvot and strengthened when we do. We are partners with God and we can’t simply expect God to automatically save us from defeat. It is better to discuss this alternative way of thinking about why God doesn’t rescue all victims of mass slaughter on Tishah B’Av rather than on Yom HaShoah, and to make a major distinction between the power of a national community in its own land to influence its fate and a small weak community in the Diaspora. Sometimes bad things do happen to good people.

Our generation lives at a time when Jews have once again re- turned to the Land of Israel and revived an independent state. A Jewish government in Israel is once again responsible for making decisions about how diverse groups of Israelis such as ultra-Orthodox, Reform, Conservative, and non-religious Jews, as well as Muslim and Christian Arabs should live together in a tolerant and peaceful society.

In addition, Jewish leaders, for the first time in more than nineteen centuries, have to decide how much to risk for war or for peace, and how to relate to Israel’s Arab neighbors. We, as individuals and as a community have much to learn from Jewish texts that provide us with wisdom from our Sages.

The Talmud relates that Rabbi Hanina said, “Jerusalem was destroyed only because its inhabitants did not reprove one another. Israel in that generation kept their faces looking down to the ground and did not reprove one another” (Shabbat 119b). Rabbi Hanina doesn’t mention any one specific action that was so reprehensible that it doomed the city. It is an attitude that he condemns.

A current example of that “not my business” attitude could be the rabbinic silence that greeted the recent decision of some ultra-Orthodox rabbis to declare null and void the conversions of thousands of Jews by proclaiming the radical innovation of “retroactive annulment” of thousands of Orthodox conversions that took place in Israel in previous years.

The sad fact is that most rabbis in Israel failed to publicly reprove these zealots for violating the Torah’s command- ments to both love converts and not in any way oppress them. Why would any of the tens of thousands of Russian non-Jews who, like Ruth, moved to Israel with their Jewish family members, want to identify with a people whose religious leaders passively abide such a disgraceful action? Who can tell what the consequences of this repulsive act of rejection will be in determining the loyalty of future generations of Israelis?

Three different historical examples of the negative consequences of rejecting even potential converts are given in Rabbinic sources. First, Me’am Lo’ez Ruth 1:14 relates that when Naomi discouraged her daughter-in-laws from returning with Naomi to Judah, Orpha stayed in Moab, remarried, and had children. Among her descendants was the great warrior Goliath, who had to be killed by David, the descendant of Ruth, the famous convert who did go with Naomi. If Naomi hadn’t discouraged Orpha, her descendant Goliath would have been fighting on the Jewish side; not on the other side.

Second, the Talmud says that when the Avot refused to accept Timna as a convert she distanced herself greatly from the Jewish people, married Elifaz, and gave birth to Amalek, who grieved the Jewish people greatly (Sanhedrin 99b). Third, the Jews suffered from being enslaved in Egypt because Abraham failed to give some non-Jews an opportunity to convert (N’darim 32a).

There was one unconventional view of two well-known biblical sins that did become somewhat orthodox in the Middle Ages. The Medieval victims of Gentile fury were guiltless because, as a minority community, they had no political power to engage in social injustice or public institutional corruption; and they were far more personally pious than Jews in the days of the First and Second Temple. No one could claim that the sins of these generations could have caused their destruction.

Therefore, the sin that caused their destruction was transferred into an archetypical one in the distant past that still doomed them: the making of the Golden Calf or the selling of Joseph. A Medieval midrash, Eileh Ezk’rah, explains that the martyrdom of ten great Sages after the failure of the Bar Kochba rebellion was “due to the selling of Joseph, whom his [10] brothers sold.”1

Also, a late Medieval midrash anthology states, “On Tishri the seventh it was decreed that the sin of the golden calf be visited upon the Israelites in every generation, and that they should die by sword, famine and plague” (Me’am Lo’ez Deuteronomy 4:26).

This later view may have already circulated in the days of Rabbi Joshua ben Levi who opposed it by teaching: “The Jews only made the Golden Calf to open the way for repentance” (Avodah Zarah 4b). The Golden Calf represents public apostasy. The selling of Joseph represents disloyalty to one’s Jewish brothers. Both of these sins did exist in Medieval times and were sometimes the stimulus for pogroms. Nevertheless, since this concept is opposed to the belief in z’chut avot (the beneficial merit of our ancestors), it never became a major theme of Tishah B’Av. However, it is evidence for how far some rabbis were willing to go in order to avoid saying that God could not, or would not, save the innocent victims of Europe’s pogroms.

Another alternative view is that history itself has up and down cycles. Some empires are severe and others are lenient. Babylon and (Seleucid) Greece were harsh while Persia and Rome were lenient. The Byzantines were harsh but Ishmael is lenient (Eichah Rabbah 1:42). There is no attempt to say that Israel’s sins determine the nature of the empire. Jewish activities might influence the timing of local events but empires have their own character. Some are just worse than others. Maybe we should not always think that whenever Jews encounter hostility and violence it is because we, or our enemies, are total sinners. Maybe some conflicts are normal and in time will pass. If oppressed religions survive they usually come out stronger. When the Temple was destroyed, the synagogue thrived. When Israel was exiled, the opportunity to bring people into the Jewish community increased.

Indeed, a rather unorthodox view of the exile is taught by Rabbi Eleazar, “The Holy One exiled Israel among the nations only in order that proselytes might be multiplied among them” (P’sachim 87b). It is true that there were many more converts to Judaism in Diaspora Jewish communities than in the Land of Israel. The strong anti-Roman feelings of many Jews in the Land of Israel not only flared into two disastrous revolts, in 66–70 C.E. and again in 132–135 C.E., but also must have expressed itself among some Jews in ongoing suspicion and hostility toward non-Jews who had converted as well as those who were interested in becoming Jewish. R. Eleazar’s teaching that gaining converts was so important that God sacrificed Jerusalem and the Holy Temple in order to multiply converts is truly radical.

Of course, it is possible that R. Eleazar was simply trying to make the best of a bad thing. But he must have thought making converts was of extraordinary importance. Perhaps R. Eleazar thought that if the Jewish people was much more numerous (like the stars in the sky or the sand on the beach) we would be a lot less likely to be defeated and oppressed by oth- ers. Thus, the failure to make large numbers of converts in the past led to the subsequent vulnerability of the Jewish people.

Another view of R. Eleazar proclaims “On the day when the temple was destroyed, there fell an iron wall, which had raised itself up between Israel and their father in heaven” (B’rachot 32b). This is the translation found on page 451 of the High Holy Days prayer book published in 1985 by the Reform Synagogues of Great Britain (the Conservative movement in GB). That the Jerusalem Temple had become an iron wall interrupting communication between Jews and God seems so radical that almost everyone avoids translating Rabbi Eleazar’s statement in its plain meaning.

The Soncino Talmud translates “Since the day the Temple was destroyed a wall of iron has intervened between Israel and their Father in Heaven,” the exact opposite meaning from that of the conservative prayer book. The verb is “to interrupt,” but what is being interrupted: the barrier created by corruption in the Temple or communication with God through the Temple?

It is true that criticism of the Temple and its priest- hood by the prophets in the generations prior to 587 B.C.E. was well known. Hosea proclaims, “I desire goodness, not sacrifice; obedi- ence to God, rather than burnt offerings” (Hosea 6:6). Even the pious book of Psalms says, “You desire no sacrifice or I would give it. You do not want burnt offerings. The sacrifices of God are a humbled heart” (Ps. 51:18–19).

Actually, both opposing meanings of R. Eleazar’s teaching are reflected in his proof text from Ezekiel: “Take an iron [serving] platter and place it as an iron wall between you and the city, and set your face against it [the city]” (Ezek. 4:2–3). Rabbi Eleazar thought that if the religious and political leaders had not ignored the moral message of the prophets, the moral walls of prophets like Jeremiah (Jer. 1:16–19) and Ezekiel would have protected the people more than the city’s walls of stone. The iron platter could be a wall block- ing communion with God, or if rotated ninety degrees, it could be a serving platter facilitating communication. It is up to us.

RAbbi Eleazar taught that the altar that should have been a horizontal serving platter bringing God and Israel together in a shared meal, but instead had been turned ninety degrees into a vertical “iron wall” of false security provided by the Temple, was now shattered again. Now our spiritual relationship with God would depend on our own personal efforts. Rapprochement with God through prayer, repentance, and good deeds would always be possible, but not automatically available through a Temple ritual. Now, with- out the sanctuary altar, Israel could energetically focus on turning the Temple’s vertical iron wall into a horizontal serving platter without the interference of political and religious corruption by a powerful priesthood.

The Talmud reports people crying out “Woe is me because of the House of Ishmael, son of Phiabi, woe is me because of their fists. For they are the High Priests, and their sons are treasurers, and their sons-in-law are trustees, and their servants beat the people with staves” (P’sachim 57a, Tosefta Minhot 13, 21). The Talmud also relates that rivalries between some priests led to bloodshed and that “the purity of their utensils was of greater concern to them than the shedding of blood” (Yoma 23a) .

This is why R. Eleazar said, “Since the day the Temple was destroyed, the iron wall between Israel and their Father in Heaven has been shattered” (B’rachot 32b). R. Eleazar sounds like an early Reform rabbi when he also teaches: “Greater is one who does charity than one who offers all the sacrifices, for it is said (Proverbs 21:3) ‘To do charity and justice is more acceptable to the Lord than sacrifice'” (Sukkot 49b). The mass spirituality of the three annual Pilgrimage Festivals to the Holy Temple has ended.

A more individual spirituality could now only be experienced from time to time in secular lands (including Israel) within holy communities that put their energy into praying, studying Torah, doing good deeds, and living a pure worldly life (B’rachot 32b). Many of these activities are not considered to be really religious by many people. Tishah B’Av should become a day devoted to understanding Reform Judaism’s view of Judaism.