A New Multilateral Bank To Boost Investment In Infrastructure In Asia – Analysis

The establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) faces major challenges in coming months. It also offers new opportunities to re-launch economic and trade relations for Europe and Asia and for international infrastructure companies.

By Jorge Dajani-González*

China’s announcement in late 2013 of an initiative to create a new multilateral bank for infrastructure investment in the least developed countries of Asia was a surprise for many, as it changed the status quo of the institutional system of multilateral banks that had been in place since the Bretton Woods conference. However, after a year of intense negotiations between the more than 50 founding countries, initial doubts about its governance, viability and timeliness have gradually dissipated. The main multilateral development banks are now cooperating actively in the process of creating this new one, which is expected to begin operations in the first half of 2016. It is estimated it could wield a portfolio of projects worth more than €30 billion in its first five years of work.

Analysis

The project to create the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) is part of the so-called ‘One Belt-One Road’ initiative, the goal of which is to favour development and interconnections between Asia and Europe. The initiative includes the countries that traditionally formed part of the Silk Road, from China and Central and Western Asia stretching to the Middle East and Europe. But the AIIB is not limited to these countries. Rather, its area of activity includes the rest of the countries of Asia and Oceania. It even opens the door to the possibility of financing projects outside its operational zone, so long as this can be useful in helping the bank achieve its goals.

The main objective is to promote greater economic and trade integration among countries that generate more than half of the world’s GDP and account for three-quarters of the planet’s energy reserves.

The infrastructure financing needs of Asia are estimated at more than US$750 billion a year,1 which means an annual investment of more than 4% of its GDP. To put this into context, the volume of loans granted annually by the Asian Development Bank is estimated at US$14 billion. Therefore, there is a lot of room for encouraging multilateral investment in infrastructure in Asia and even bringing in new actors. Otherwise, a good part of these infrastructure projects would require strictly national or private financing, which would be more expensive, or would simply fail to be undertaken, exerting a negative impact on growth, productivity and employment.2

The initiative of creating the AIIB was a proposal by the Chinese President Xi Jin Ping, with the goal of financing large-scale infrastructure projects. From the outset, the emphasis has been on the need for the bank to work together with other existing multilateral financing institutions. It is an inclusive initiative, and this has earned it early support from the international community, both from multilateral institutions and most European countries.

The potential founding members are those that signed the Memorandum of Understanding and those that, like Spain and the rest of the countries of Europe, presented requests to become founding members by 31 March 2015.

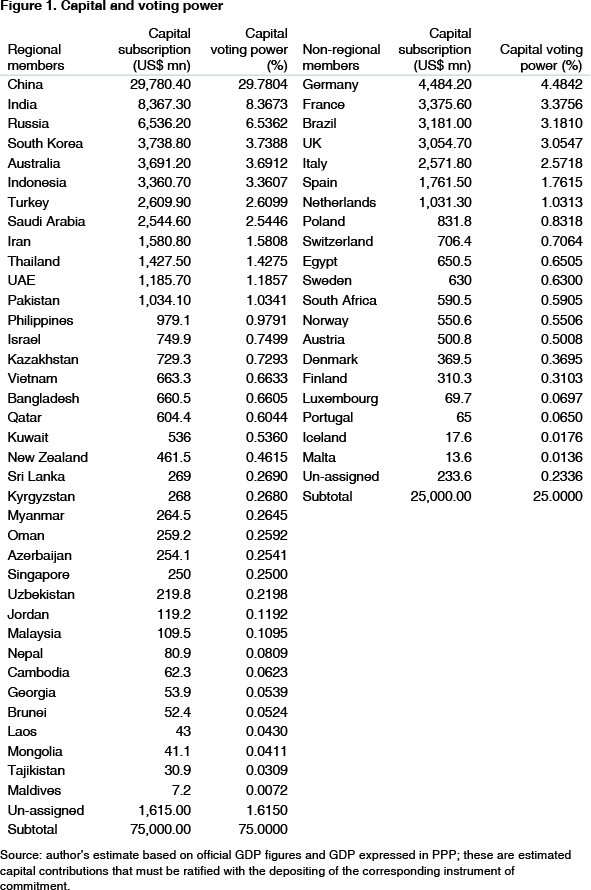

After five rounds of negotiations, on 29 June 2015 the Articles of Agreement were signed in Beijing, where the bank’s headquarters will be located, although it will be able to set up agencies or offices in other countries. Currently, 57 countries (see Figure 1) are listed as potential founding members. They will become fully-fledged members once the bank is formally constituted, presumably in late 2015. The highest-profile absences include the US, Japan and Canada.

The bank’s authorised capital stock totals US$100 billion. It is divided into paid-in shares, which account for 20% of the total, and callable shares, which account for the remaining 80%. Countries have five years to pay 20% of the paid-in shares.

Capital subscribed by the countries of Asia and Oceania cannot be less than 75% of the total subscribed capital. So the US$100 billion authorised capital has been distributed so that 75% comes from regional countries and 25% from countries outside the region. These amounts have been further distributed within each group by using a formula based on indicators related to GDP (60% of GDP at market prices; 40% of GDP in purchasing power parity).

The bank will have a Board of Governors which will hold all of its powers, as well as a Board of Directors, which will carry out whichever functions are delegated to it by the Board of Governors. The Board of Directors will be made up of 12 directors, each of whom will be assisted by two alternate Directors. The make-up of the Board of Directors will be as follows:

- Nine Directors will be chosen by Governors who represent the regional members from Asia and Oceania.

- Three Directors selected by Governors representing non-regional members.

The Board of Directors will be of a non-resident nature. In other words, the Directors and alternates will not live in Beijing, nor will they earn salaries from the bank. Rather, they will travel to scheduled bank meetings. This non-resident feature, which is similar to the system used by the European Investment Bank, and the reduced number of Directors introduces an operating procedure in line with the principles of the Bank: Lean, Green and Clean.

Plans are for the number of bank employees to not surpass 600. The maximum degree of transparency will be required, such as, for instance, the publication of the minutes and resolutions of the Board of Governors. The Bank will also observe the best corporate ethics practices by establishing two codes of conduct that will set clear ethics and conflict-of-interest standards that will be applied to all the members of the Board of Directors, the management staff and bank personnel. The Bank will have a President chosen by the Board of Governors who will be from a regional member country; the mandate will last five years, and this incumbent can be re-elected only once. In the sixth round of negotiations, which took place in Tbilisi, Georgia on 24 August, Jin Liqun was chosen President-Elect. He has broad management experience both at the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, as well as in other relevant financial and governmental institutions.

The total number of votes allotted to each member country will be the sum of their ordinary or basic votes,3 their votes per subscribed share and in the case of founding members the 600 votes they have due to their status as such.

Figure 1 shows the approximate figure for the votes that each country will have, taking into account the amount that each country has said it was to subscribe, without including ordinary or basic votes or the votes that come with being a founding member. The Articles of Agreement set out three possible majorities when it comes to approving decisions made by the Board of Governors:

- The most frequent case will be that of majority of votes cast.

- Special majority within the Board of Governors. This involves a majority of the total number of Governors representing at least a majority of the total number of votes of the members. The kind of decisions that can be adopted with this kind of majority include the acceptance of new members, the issuance of shares at a value that is not at parity, and the creation of affiliated entities.

- A qualified majority on the Board of Governors. This means two-thirds of the total number of Governors representing at least three-quarters of the total number of votes of the members. Decisions that can be taken with this kind of majority include letting the percentage of capital subscribed by the regional members be less than 75% of the total subscribed capital, the makeup of the Board of Directors, modifying the non-resident nature of the Board of Directors, the election of the bank’s Secretary General and his or their dismissal, suspension of a country’s membership and changes to the Articles of Agreement.

The qualified majority rule means de facto that a country with more than 25% of the capital, as is the case of China, can exercise its veto right in a series of decisions spelled out in the charter. In other international financial institutions, this veto power is lowered to the threshold of 15%.

One of the touchiest issues for the AIIB is to dispel doubts about the safeguard policies it plans to require of projects so as to guarantee minimum standards of social and environmental protection. Here, the bank is at an advanced stage in its work to devise and adopt codes based on the best international practices. The three main areas of attention are these: (1) analysis of the social and environmental impact of any project, keeping in mind in particular the protection of vulnerable communities, women and children, as well as the fight against climate change and pollution; (2) minimising unwanted displacement of people and ensuring that beneficial alternatives are always offered to those most affected by bank projects; and (3) protecting the identity, dignity and rights of indigenous peoples, who must participate actively in the design of projects when in some way they are affected by them.

As for government procurement, the bank’s work is also well advanced and includes some important new features. For instance, procurement policy will have no geographical restrictions, so there will be an even playing field for any supplier to bid on contracts for goods, work or services. The guiding principles will be transparency and value for money, which means AIIB must obtain the best possible return for the resources that are available. Of course, this includes the principles of efficiency and adopting policies of in-country procurement so long as the minimum requirements set by the bank are met.

In the initial phase (2016-18), the bank’s investments will probably concentrate on high-priority sectors such as transport, energy and water. But once the bank is fully up and running the focus of the projects can broaden to include environmental protection, urban development, information technologies and telecoms, rural infrastructure and agricultural development.

The AIIB’s investment policy will cover all financing instruments: direct loans, stakes in the capital of institutions or companies, guarantees, special funds, technical assistance or any other kind of financing that the Board of Governors opts for.

Most likely, the first transactions will be co-financed with other multilateral development banks and probably be high-volume operations. Once the bank has all the staff it needs, it will begin to lead projects involving smaller amounts of financing and operations with the private sector.

In the end, the AIIB will be able to leverage financing to a maximum of 2.5 times its subscribed capital, so that the maximum amount could rise to US$250 billion. In practical terms, it is estimated that by the end of its fifth year of operations, the bank’s portfolio of investment could exceed €30 billion.

As for financing in capital markets, the procedure will be very similar to that followed by other multilateral development banks, with the added advantage that it will presumably enjoy a top-quality credit rating. This will in turn reduce substantially the financing costs of countries that borrow. In August, the Moody’s agency issued a statement to the effect that AIIB is credit positive for the emerging economies that are part of it.

Mobilising private financing to co-finance this kind of project –public assets of a large size, over long periods of time and without liquidity– can be complicated. However, there is currently a large number of funds, both private infrastructure funds as well as pension funds and sovereign funds, that are increasingly interested in participating in these kinds of long-term operations. The AIIB can also provide the benefit of legal security, management capability and risk monitoring that make it more attractive for private investors to take part in this kind of project.

From the very beginning Spain has been playing an active role in the creation of this new bank, of which it is a founding member and one of the sixth-largest non-regional shareholders. This is not just a reflection of the Spanish government’s commitment to the multilateral system of international financing designed to encourage the development of the less advanced economies. Rather, it also represents a firm support for increasing economic and commercial ties with Asia and offering new business opportunities to the Spanish companies with the most international scope, especially those most directly involved in construction and infrastructure management.

Spain will make an initial contribution of US$1.761 billion, which will give it a voting percentage of nearly 1.8%, higher than what it currently has at the Asian Development Bank.

Another important point involves the business opportunities that are going to be created for Spanish infrastructure companies: new projects in the Asian market, which is probably the one with the greatest potential anywhere in the world, and with the security of investment backed up by an international financial organisation such as the AIIB.

It seems realistic to expect Spanish companies will win 3%-5% of all contracts, taking into account the fact that Spanish firms in recent years have been in second place in terms of contracts won by non-regional companies in analogous banks such as the Asian Development Bank. One must also keep in mind the prestigious international position that the main Spanish infrastructure companies enjoy.

About the author:

*Jorge Dajani-González, Director General of Macroeconomic Analysis and International Economics, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain)

Source:

This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute

References

Asian Development Bank Institute (2009), Infrastructure for a Seamless Asia.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (2015), “Articles of Agreement of AIIB”.

Canning, D., and P. Pedroni (2008), ‘Infrastructure, Long-run Economic Growth and Causality Tests for Cointegrated Panels’, The Manchester School, nr 76, p. 504-527.

Fung, K.C., A. Garcia-Herrero and F. Ng (2008), Foreign Direct Investment in Cross-Border Infrastructure Projects, ADBI, Tokyo.

Kuroda, H., M. Kawai and R. Nangia (2007), ‘Infrastructure and Regional Cooperation’, ADBI Discussion Paper, nr 76, Tokyo.

1 ‘Infrastructure for a Seamless Asia’, Asian Development Bank Institute, 2009.

2 Analysis of the impact of infrastructure on economic growth and productivity has a long tradition in economic literature, starting with Robert Barro’s initial model of endogenous growth in 1990 through more recent analyses such as the Canning and Pedroni model, which also incorporates the beneficial effects of infrastructure on income equality.

3 The ordinary or basic votes of each member are calculated as follows: an equal division among all the countries of 12% of the aggregate sum of the ordinary or basic votes, the votes per share and the votes of the founding members. This formula has an offsetting effect that favours smaller countries, and yields a percentage slightly below that used by analogous banks.