What Is ‘Technology Of The Color Revolutions’: Why It Occupies Such A Prominent Place In Russian Threat Perceptions – Analysis

By Mitchell Binding*

For the last several years, scholars and military practitioners alike have been preoccupied with the actions of Russia in Ukraine and Syria, and what this new trajectory means for global peace and security. In order to better understand the factors that underlie this complex geopolitical situation, it is necessary to examine Russia’s understanding of the ‘technology of colour revolutions,’ and why it occupies such a prominent place in Russian threat perceptions. This article begins with an explanation of what exactly constitutes the ‘technology of colour revolutions,’ and follows by providing examples of when and where Russia has perceived these technologies. An analysis of why Russia views this as an existential threat follows, and the article concludes with an opinion as to how the West can approach this problem.

What is it?

Colour revolutions are widely understood as a phenomenon whereby popular protests dislodge an incumbent party from power. Beyond this basic agreement, however, Russia and the West disagree strongly with respect to how they come about, and for what purpose they exist. The narrative in the West maintains that colour revolutions are essentially organic uprisings that manifest in corrupt and authoritarian regimes. The West politely defines them as “…non-violent mass protests aimed at changing the existing quasi-democratic governments through elections.”1 Similarly, they have been described as “…counter-elite-led, non-violent mass protests following fraudulent elections.”2 An important point is that colour revolutions are understood as a natural step in the process of democratization.3 It is also worth noting that Western observers do not see external assistance as necessary (although not unhelpful) for a colour revolution to take place.

Russia has a very different view, and it cannot be explained simply by alternative ‘narratives.’ Starting from the neo-Hobbesian worldview that global powers are in a state of competition and inevitable rivalry, Russia views the West’s support of colour revolutions as nothing more than a lever of strategic power to be utilized in the expansion of Western influence.4 They are seen as a set of tools used by the West to bring down regimes with which it disagrees. Further, colour revolutions are not simply the utilization of tools of propaganda – they exploit the mobilisation and weaponization of popular protest toward the violent overthrow of a standing government ‘by the people.’ This provides ‘legitimacy’ of the action itself, but also an opportunity for intervention by foreign government to assist the ‘democratic’ over throwers.

Russia’s view of colour revolutions as such can be appreciated. Russian history abounds with episodes of invasion, revolution, and collapse. The 20th Century was particularly traumatic for Russia. “[It] suffered two world wars, absorbing colossal human and material losses; [saw] two empires collapse; experienced unspeakable levels of domestic repression; and at virtually no stage enjoyed a comfortable relationship with its neighbors or the wider world.”5 This likely explains President Vladimir Putin’s opinion that “Revolutions are bad. We have had more than enough of those revolutions in the 20th Century.”6

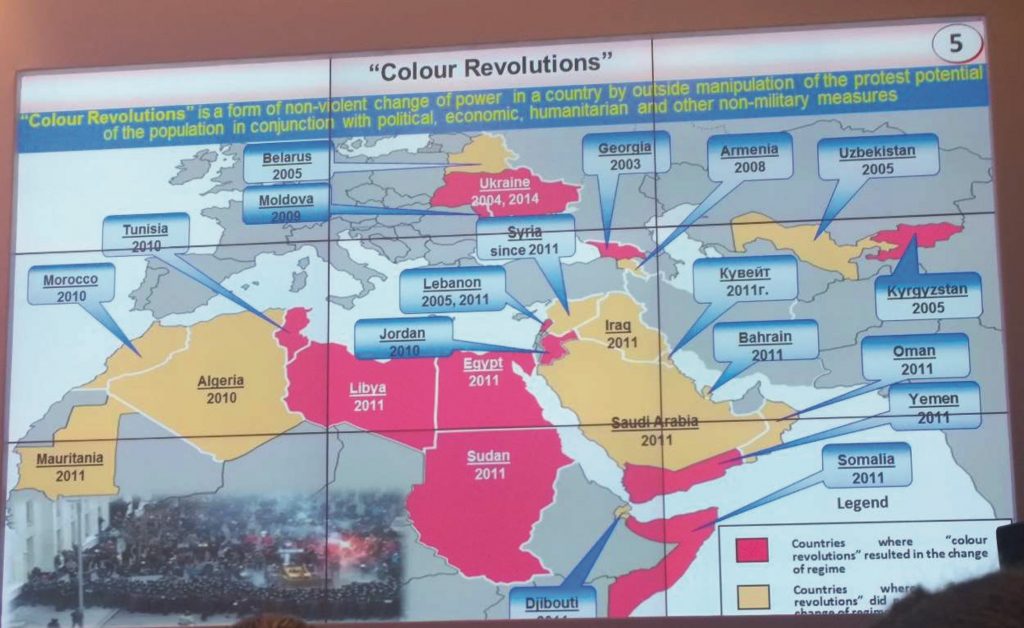

Viewed from this context, Russia observes colour revolutions occurring around the globe, and the West’s unconditional support for them, and fears that they mask underlying objectives of ‘normative hegemony’ under the guise of support for human rights.7 This helps explain the Russian conceptualization of colour revolutions that diverges so markedly from the Western conceptualizations. The view is that they are “…orchestrated by the US and the European Union in order to isolate Russia within a belt of hostile nations or area of instability.”8 Sergey Lavrov, the Foreign Minister of Russia, called colour revolutions “unconstitutional change of government,” and argued that they are “destructive for the nations targeted by such actions.”9 Valery Gerasimov, the Chief of General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, defined colour revolutions as “…a form of non-violent change of power in a country by outside manipulation of the protest potential of the population in conjunction with political, economic, humanitarian and other non-military measures.”10 Again, the focus is upon the fact that popular protests are instigated and supported by outside manipulation, ostensibly for foreign strategic objectives.

Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces General Valery Gerasimov before a meeting with Defence Ministry leadership and representatives of the military-industrial complex in Sochi, Russia, 12 May 2015.

Russia views the West fomenting these colour revolutions with particular ‘technologies.’ These include “…long-term foreign cultivation and financing of an internal opposition and general divisions within society; creation or co-optation of an opposition elite; foreign [non-governmental organizations] NGOs and outside agents advocating ‘globalisation’ and ‘westernisation;’ campaigns in support of democracy; and exploitation of elections.”11 These technologies also include ‘professional coordination centers,’ emotional engineering of protesters, control of mass media and alternative media, and Public Relations specialists.12 These methods supplement large-scale information wars, and the use of generous legal discourse to conceal true objectives.13 General Gerasimov adds to this list the military training of rebels by foreign instructors, supply of weapons and resources to anti-government forces, application of Special Operations Forces and private military companies, and the reinforcement of opposition units with foreign fighters.14 It should be noted that the perception of these ‘technologies’ may simply be Russia seeing in the West some of its own methods, such as the use of ‘electoral technologies’ such as the media, and their own method of lending ‘political technologists’ to preferred candidates in target countries’ domestic politics.15

Historical Precedents

Russia sees these attempts by the West to subvert legitimate political regimes everywhere it looks. General Gerasimov, at the third Moscow Conference on International Security in 2014, sought to demonstrate Western involvement in precisely 25 colour revolutions, spreading across the Middle East, Africa, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe (see Figure 1 below).16 This article will only focus upon a few key revolutions that played major roles in developing Russia’s current threat perceptions. The first was the so-called Bulldozer Revolution in Yugoslavia in 1999. For many Russian military and political leaders, this was the watershed moment where everything changed. President Putin expressed to the Kremlin: “This happened in Yugoslavia; we remember 1999 very well.”17 The first colour revolution in post-Soviet Eurasia was unexpectedly successful in using non-violent protest to oust an autocratic leader, and henceforth became a role model for future movements.18 The mobilization of mass protests was linked to ‘training’ in non-violent methods in the United States, and the involvement in the country of foreign-linked NGOs – which was enough for Russia to view the colour revolution in Yugoslavia as artificial.19

Not long thereafter, the 2003 Rose Revolution occurred in Georgia, raising the stakes by occurring right on Russia’s doorstep, and bringing the phenomenon into the post-Soviet sphere. Once again, the mass mobilization of protesters was supported by the formation of civil society groups that included some ‘trained and funded by Western organizations’.21 As in Yugoslavia, the matter was made worse by the failure of Russia to prevent the democratic movement, as well as the imposition of a new leader, who was West-leaning. These circumstances, coupled with the desire to reassert some semblance of authority, eventually led to the ‘Five-Days War’ in 2008, which resulted in a Russian invasion and restoration of authority.22

The 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine particularly enraged Russia. Here was another colour revolution within the post-Soviet space, but this time the West was apparently able to plant the seed of mass protests in a heretofore stable and increasingly prosperous country.23 The unexpectedness of the uprising fuelled the Russian perception that the West was manipulating the electoral process to replace incumbent leaders with those favourable to their foreign policies.24 Furthermore, the upset in the unconventional third round of voting that saw Russia’s pick for president lose to the West’s preferred candidate stung Putin personally. Russia had a close relationship with Ukraine and felt it had significant influence in its politics, and Putin had personally travelled to Ukraine twice during the campaign to support the East-leaning incumbent.25 When Putin’s candidate lost, it not only reaffirmed the conviction that the West was going too far in its interference, it was seen as a personal affront.

Finally, the most widespread of the colour revolutions was the Arab Spring in 2011. President Putin again recounted to the assembled Kremlin that a whole series of controlled ‘colour revolutions’ took place, in which the West cynically took advantage of the peoples’ legitimate objection to tyranny.26 In this, “…standards were imposed on these nations that did not in any way correspond to their way of life, traditions, or … cultures. As a result, instead of democracy and freedom, there was chaos.”27 Russia learned several lessons from the colour revolutions of the Arab Spring that have informed their threat perceptions. First, the potential of social media to mobilize populations, and even to facilitate regime change, became very clear.28 Second, military leaders observed that “…a perfectly thriving state can, in a matter of months or even days, be transformed into an area of fierce armed conflict, become a victim of foreign intervention, and sink into a web of chaos, humanitarian catastrophe, and civil war.”29 Furthermore, General Gerasimov derived from these lessons that the ‘rules of war’ had changed, to the extent that “…non-military means of achieving political and strategic goals [had] grown, and, in many cases…exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness.”30 These lessons were accepted so thoroughly that they altered the (previously discussed) Russian military doctrine, and have subsequently been seen at work in Ukraine and Syria.

Russian Threat Perceptions

These foregoing examples, which occurred over the last twenty years, have solidified to Russia the threat that it faces from the West. As a vector for influencing or bringing down the Russian regime, it is viewed as the most likely approach in order for conflict to remain unattributable, and under the threshold for retaliation. This is why the 2014 Russian military doctrine listed the destabilization in ‘certain states and regions’ as one of its main external military threats, as well as the internal destabilization of the political and social situation in the country, provocation of ‘interethnic and social tension and extremism,’ and information operations influencing the population, especially ‘young citizens.’31 This fear comes from the events of the colour revolutions reviewed thus far, but most of all, from the perceived attempt at a colour revolution within Russia in 2011–2012. This event was the manifestation of the Kremlin’s worst fears – that the unrest and political instability would spread from the Middle East, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe, and infect the Motherland as well. Following the re-election to a third term of President Putin, popular protest regarding perceived political corruption and fraud shook the Russian regime.32 Protest movements with 120,000–200,000 citizens (over 10% of Moscow’s population) were recorded, and Russia was nearly paralyzed for a matter of months.33 President Putin and the Kremlin had been very prepared for such an event, however, and successfully diffused the protests using all the tools of the state at their disposal, both forceful and persuasive.34 Mass media and counter protests were utilized to entrench the message that the protesters were ‘foreign-backed revolutionaries’ intent upon regime change and bloody civil war.35

The perception in Moscow that the West had attempted a colour revolution in Russia had immediate consequences. Australian writer, foreign policy expert, and former diplomat Dr. Bobo Lo maintains that: “Putin’s personal sense of ‘obida’ (offense) at U.S. support for the public demonstrations against him… was the single most important reason behind the hardening of Russian policy toward Washington.”36 These events also motivated the hardening in Russian threat perceptions toward potential technologies of colour revolutions.

The manifestation of these perceptions can be seen in the suspicions cast upon foreign NGOs, and especially those linked to Western money or promoting Western values.37 These suspicions motivated the passing of the 2012 Foreign Agent Law, as well as the 2015 Undesirable Organizations Law, giving the Russian government the authority to curb foreign-linked organizations that were believed to be supporting nefarious democratic movements (i.e., the National Endowment for Democracy, the Soros Foundation, and so on).38 Even more concretely, the 2014 Russian military doctrine very clearly established colour revolutions as a primary threat, both internally and externally. It confronts activities meant to affect “…the sovereignty, political independence, and territorial integrity of states,” as well as “forcibly changing the constitutional system of the Russian federation,” and “destabilizing the internal political and social situation;” in response, the newest military doctrine promises to “neutralize possible military dangers and military threats by political, diplomatic, and other non-military means,” and to “develop and realize measures aimed at increasing the effectiveness of military-patriotic indoctrination of citizens.”39

Further implications of this hardened stance are that Russia has concluded it must display aggression to prevent the West from thinking it can push Russia too far. In Russia’s view, if non-aggression is the axiom behind colour revolutions, then to counter a colour revolution, the violence must be escalated.40 This is the reason why many observers consider Russian interference in Ukraine and Syria to be just such counter-revolutions; not only did they derail insipient mobilizations, Russia (in their view) successfully played back the West’s own liberal and legal discourse to justify its actions.41 An additional benefit has been the widespread domestic support for President Putin’s forays abroad, which surely helps to allay fears of another uprising.42 However, this successful counter colour revolution has not entirely dissipated Russian unease. The Russian Security Council released its analysis in 2015 that there was ‘great risk’ that the West may attempt another colour revolution in Russia in order to oust the current political regime, and to maintain global hegemony.43 The Secretary of the Security Council, Nikolay Patrushev, further elaborated that the West continued to finance opposition forces while simultaneously imposing economic sanctions with the hope of causing mass protests in Russia.44 This threat is viewed as existential, since the political system in Russia is “…centered on individuals and their networks rather than formal institutions.”45 In fact, it has been argued: “No single person in the six decades since the death of Stalin has been so intimately identified with power and policy in Russia. Putin has become synonymous with political Russia.”46 This perpetual preparedness for Western interference provokes the Kremlin to search for ways to push back, and creates a scapegoat that is useful for unifying the Russian people – who themselves fear insecurity and collapse on a cultural level – against a common enemy.

How to move forward?

The final remarks should be to consider what exactly the West should do with this understanding of Russian threat perceptions regarding the technologies of colour revolutions. Naturally, it should be presumed that Russia’s leaders will utilize all manners of statecraft at their disposal to protect the national interests of Russia, including the use of narratives and counter-narratives (i.e., information operations) to convince domestic and international citizens that Russia is in the right, and that the West in the wrong.

Nevertheless, the West should equally acknowledge that Russian threat perceptions and concerns for the stability of its political regime and social situation are legitimate. Opportunities should be sought for constructive engagement and accommodation, even within the current context of sanctions and opposing narratives surrounding Russian involvement in Eastern Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. A further complicating factor is the ongoing investigation into Russian ‘meddling’ in the 2016 United States elections (one could say their own attempt at a colour revolution). Given the highly contentious nature of the issues on both sides of the divide, engagement will be difficult. There is surely the concern that ‘giving an inch’ now will result in ‘losing a mile’ later, especially if Russia and others ‘learn’ that current behaviour is the key to winning concessions. However, in the current climate, and especially since Russia views non-military action as potential military threat, the threat for escalation remains and should be avoided. Unfortunately, for the foreseeable future, a prevention of escalation is likely the best that can be achieved.47 Less optimistically, the implication that both Russia and Western countries perceive that the other is working to destabilize and overthrow their political and social order may prevent any cooperation whatsoever, and thus, defensive lines will be fortified, alliances strengthened, and escalation anticipated.

Conclusion

To wrap up this brief analysis, within this confusing state of global affairs, and given the increase in unattributable interference by different actors, it is important for Western academics and security practitioners to appreciate the Russian view with respect to the technologies of colour revolutions, and the prominent place they hold in Russian threat perceptions. This Russian perspective is underwritten by a hostile interpretation of popular protests in a large number of countries – most specifically Yugoslavia, Georgia, Ukraine, the Arab Spring, and in Russia itself. This deeper appreciation by the West will foster a better understanding of the global security environment and future conflict trajectories, but will also help to lessen misunderstandings between Russia and the West, and reduce the likelihood of future hostility.

About the author: Captain Mitchell Binding is a pilot with 408 Tactical Helicopter Squadron in Edmonton. This article represents research completed for a Master’s degree in International Relations and Contemporary Warfare from King’s College London.

Source: This article was published by the Canadian Military Journal, Volume 19, Number 4, Page 54.

Notes:

- Ieva Berzina, ‘Color Revolutions: Democratization, Hidden Influence, or Warfare?’ National Defence Academy of Latvia Center for Security and Strategic Research 01/14 (2014). p. 3, at: http://www.naa.mil.lv/~/media/NAA/AZPC/Publikacijas/WP%20Color%20Revolutions.ashx.

- Julia Gerlach, ‘Mapping Color Revolutions,’ in Color Revolutions in Eurasia (Springer International Publishing, 2014), p. 3, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-07872-4_2.

- Ieva Berzina, p. 10, at: http://www.naa.mil.lv/~/media/NAA/AZPC/Publikacijas/WP%20Color%20Revolutions.ashx.

- Bobo Lo, Russia and the New World Disorder (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), p. 40.

- Ibid, p.18.

- ‘Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club,’ President of Russia, 24 October 2014, at: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/46860.

- Richard Sakwa, ‘The Death of Europe? Continental Fates after Ukraine,’ in International Affairs 91, No. 3 (2015), pp. 557-558, DOI: 10.1111/1468-2346.12281.

- Dave Johnson, ‘Russia’s Approach to Conflict: Implications for NATO’s Deterrence and Defence,’ NATO Defence College No. 111 (2015), p. 5, at: http://www.ndc.nato.int/news/news.php?icode=797.

- Sergey Lavrov, ‘Russia’s Foreign Policy: Historical Background,’ The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 3 March 2016, at: http://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/

id/2124391. - Anthony H. Cordesman, ‘Russia and the Color Revolution: A Russian Military View of a World Destabilized by the US and the West (Full Report),’ Center for Strategic & International Studies (2014), p. 17, at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-%E2%80%9Ccolor-revolution%E2%80%9D.

- Dave Johnson, p. 5, at: http://www.ndc.nato.int/news/news.php?icode=797.

- ‘US “World Leader” in Color Revolution Engineering,’ RT, 25 April 2012, at: https://www.rt.com/news/color-revolutions-technology-piskorsky-938/.

- Sergey Lavrov, at: http://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/

id/2124391. Roy Allison, ‘Russian Deniable Intervention in Ukraine: How and Why Russia Broke the Rules,’ International Affairs 90, No. 6 (2014): p. 1258, https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/90/6/1255/2326779?redirectedFrom=fulltext. - Anthony H. Cordesman, p. 18, at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-%E2%80%9Ccolor-revolution%E2%80%9D.

- Dov Lynch (ed.) ‘What Russia Sees,’ EU Institute for Security Studies Chaillot Paper No. 74 (January 2005), pp. 13, 59, at: https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/what-russia-sees.

- Anthony H. Cordesman, p. 17, at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-%E2%80%9Ccolor-revolution%E2%80%9D.

- ‘Address by the President of the Russian Federation,’ President of Russia, 18 March 2014, at: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603.

- Julia Gerlach, ‘Mapping Color Revolutions…,’ p. 4.

- Ibid, p. 5; ‘October 5, 2000: Flashback to Yugoslavia, West’s First Color Revolution Victim,’ RT, 5 October 2017, at: https://www.rt.com/op-ed/405771-october-2000-remembering-yugoslavia-nato/.

- Anthony H. Cordesman, Russia and the “Color Revolution”: A Russian Military View of a World Destabilized by the US and the West (Full Report), 28 May 2014, p. 17, at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-%E2%80%9Ccolor-revolution%E2%80%9D.

- Julia Gerlach, ‘Mapping Color Revolutions…,’ p. 7.

- Ibid, p. 8.

- Ibid, p. 9.

- Roy Allison, p. 1289, at: https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/90/6/1255/2326779?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- Dov Lynch (ed.) ‘What Russia Sees,’ EU Institute for Security Studies Chaillot Paper No. 74 (January 2005), p. 13, at: https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/what-russia-sees.

- ‘Address by the President of the Russian Federation,’ President of Russia, 18 March 2014, at: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603.

- Ibid.

- Keir Giles, ‘Russia’s “New” Tools for Confronting the West: Continuity and Innovation in Moscow’s Exercise of Power,’ Chatham House (2016), p. 29, at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/2016-03-russia-new-tools-giles.pdf.

- Mark Galeotti, ‘The “Gerasimov Doctrine” and Russian Non-Linear War,’ In Moscow’s Shadows (Blog), 6 July 2014, at: https://inmoscowsshadows.wordpress.com/2014/07/06/the-gerasimov-doctrine-and-russian-non-linear-war/.

- Ibid.

- ‘Kremlin Publishes New Edition of Russian Military Doctrine,’ BBC World Monitoring, 1 January 2015, paras. 12-13, at: https://www.nexis.com/auth/checkbrowser.do?t=1532847610433&bhcp=1.

- Ieva Berzina, ‘Color Revolutions: Democratization, Hidden Influence, or Warfare?’ National Defence Academy of Latvia Center for Security and Strategic Research 01/14 (2014), p. 17, at: http://www.naa.mil.lv/~/media/NAA/AZPC/Publikacijas/WP%20Color%20Revolutions.ashx.

- Julia Gerlach, ‘Mapping Color Revolutions…,’ p.22; ‘Russia “Faces Orange Revolution Threat” After Polls,’ Sputnik International, 21 February 2012, at: https://sputniknews.com/russia/20120221171440562/.

- Ieva Berzina, ‘Color Revolutions…’ p. 17, at: http://www.naa.mil.lv/~/media/NAA/AZPC/Publikacijas/WP%20Color%20Revolutions.ashx.

- ‘Russia “Faces Orange Revolution Threat” After Polls,’ in Sputnik International, 21 February 2012, at: https://sputniknews.com/russia/20120221171440562/.

- Bobo Lo, p. 8.

- Andrew Korybko, ‘Crowdfunding the Color Revolution,’ Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (2016), at: https://en.riss.ru/analysis/19488/.

- Ibid.

- ‘Kremlin Publishes New Edition of Russian Military Doctrine…,’ paras. 12-13 and 21, at: https://www.nexis.com/auth/checkbrowser.do?t=1532847610433&bhcp=1.

- Ieva Berzina, ‘Color Revolutions…,’ p. 13, at: http://www.naa.mil.lv/~/media/NAA/AZPC/Publikacijas/WP%20Color%20Revolutions.ashx.

- Roy Allison, p. 1259, at: https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/90/6/1255/2326779?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- Bobo Lo, p. 31.

- ‘Risks are High US May Use Colour Revolution Technique in Russia – Security Council,’ TASS News Agency, 25 March 2015, at: http://tass.com/russia/784857.

- ‘US Hoped to Cause Mass Protests in Russia by Sanctions – Senior Security Official,’ TASS News Agency, 5March 2015, at: http://tass.com/russia/781118.

- Bobo Lo, p. 7.

- Ibid.

- Margarete Klein, ‘Russia’s New Military Doctrine: NATO, the United States and the “Colour Revolutions,” German Institute for International and Security Affairs Comments 9 (2015), p. 4, at: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/russias-new-military-doctrine/.; Keir Giles, ‘Russia’s “New” Tools for Confronting the West: Continuity and Innovation in Moscow’s Exercise of Power,’ Chatham House (2016), p. 69, at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/2016-03-russia-new-tools-giles.pdf.