Weaponizing Markets – Analysis

Western hedge funds, banks and short sellers are targeting China, Hong Kong, and South Korea. As geopolitics is proliferating in Asia, weaponization is spreading to markets.

Hong Kong stocks have been plunging to losses for the fourth straight year. In South Korea, global banks have intentionally and illegally shorted companies.

As Chinese authorities began to consider a package of measures to stabilize the slumping stock market aiming to get some $278 billion through offshore entities, Hang Seng Index recorded biggest one-day gain in more than two months on Wednesday, rebounding from the lowest level since October 2022.

But why are real economies bleeding when they seem to be rebounding? Here’s the simple answer: These seemingly disparate events do have a common denominator. Following the weaponization of trade and technology markets since 2017, markets are being weaponized.

UK, Western European and US short sellers in South Korea

In mid-October 2023, as quarantines were being dismantled and markets opened, South Korea’s stock market watchdog (FSS) said two Hong Kong-based global investment banks, HSBC and Bank BNP Paribas, were engaging in naked short-selling. The shorting amounted to $30 million and $12 million, respectively.

“Naked short selling” of stocks – in which an investor short sells shares without first borrowing them or determining they can be borrowed – is banned in South Korea. So, the FSS fined the global banks the largest-ever penalties for illegal short selling.

In South Korea, the number of identified illegal cases more than doubled in 2022-23. In the past, most shorters have been hedge funds. Now global investment banks were found guilty of intentional illegal short selling. The fines have not halted the shorting.

As the financial regulators tackled the destabilization, participation by global funds in trading in South Korea’s $1.8 trillion stock market declined. By early December, foreign investors accounted for 18% of total market turnover by value, on course for the lowest monthly level of the year.

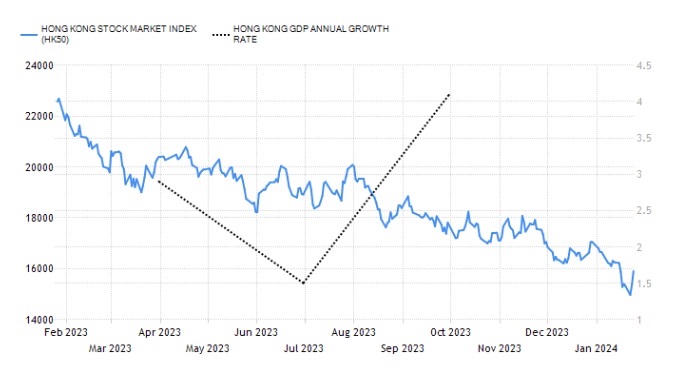

Yet, in South Korea the destabilization has not undermined the link between the market (KOSPI) and GDP growth. In Hong Kong, it has.

Shorting from Hong Kong to China

In Hong Kong, the Hang Seng Index finished the last trading day in 2023 14% lower than it started the year. Similarly, stocks in mainland China recorded losses, with the CSI 300, an index tracking companies listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen, declining 11%. In both cases, the declines have led to hundreds of billions of dollars flowing out as money managers and pension funds reduced their holdings in Hong Kong; the longstanding gateway for foreign investors wanting to put money into mainland China (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Hong Kong: markets and economy: 1-year perspective

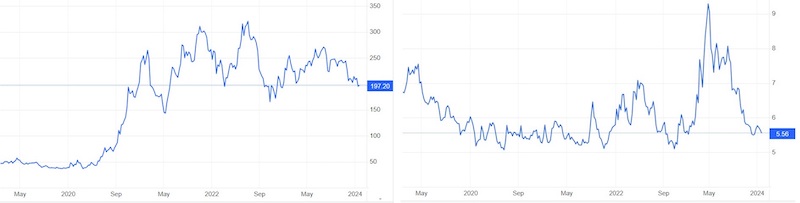

Here are two examples representing “old” and “new” industries. The BYD became the top-selling battery electric vehicle manufacturer in the world after overtaking Tesla in the fourth quarter of 2023 and Volkswagen, the first time any carmaker outsold the German brand since at least 2008. Yet, BYD stock has been plunging since mid-2023 and remains 30% below its high.

China Railway (CR) is the Chinese passenger and freight railroad giant. As tourism outflows are still struggling around the world, domestic tourism in China has soared. During the impending Chinese New Year, a record high 9 billion trips will likely be made, with the national railway system expected to complete 480 million passenger trips. How are these realities reflected by the CR stock, a major beneficiary? Well, they aren’t. It’s been plunging ever since last May and remains 40% down from its high (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Stocks Under Pressure: 1-year perspective

Short sellers from Chanos to Ackman and Bass

Like South Korea, Hong Kong began to attract short sellers soon as the quarantines ended. These players are exemplified by billionaire players, such as Pershing Square boss Bill Ackman, who recently played a key role in the ousting of Harvard’s first black female president Claudine Gay, had first tried to exploit the Hong Kong dollar a decade ago. He took another tilt in 2022, betting the government would be forced to break its link to the US dollar. Fellow hedge-funder Kylie Bass has made similar pronouncements since at least 2019.

Following the highly controversial short-sellers like Andrew Left and Carson Block, Ackman and Bass have targeted China. Bass bet on banking collapse in China in 2015-19 and plays a role in the ultra-hawkish think-tank Hudson Institute, which promotes regime change in China.

The two were preceded by Jim Chanos, who in 2009 bet against Chinese real estate; right before the Chinese stock boom. A year later, he predicted an impending Chinese economic crash that would resemble “Dubai times 1,000 – or worse.” Despite years of flawed predictions, New York Times portrayed Chanos glowingly as “The Man Who Got China Right” in 2015, which is how he is still portrayed by CNBC and US news media.

Yet, the cold reality is that last fall Chanos shuttered his hedge funds, which fell 4% even as the S&P500 surged 18%.

Shorting in China

Headquartered in the US, UK, Western Europe and Japan, international media has reported China’s ongoing rebound mainly as a “downturn,” “meltdown,” or even “collapse.” In reality, the Chinese recovery began in April-July, slowed in August-October, but has strengthened thereafter. Yet, through this period the Chinese market has declined, even as rebound has broadened (Figure 3).

Figure 3 China: markets and economy: 1-year perspective

Nearly nine-tenths of the foreign money that flowed into China’s stock market in 2023 left prior to the year-end. Since peaking at 33 billion in August, net foreign investment in China-listed shares in 2023 dropped 87%, according to Financial Times calculations based on data from Hong Kong’s Stock Connect trading scheme.

International investors have been persistent net sellers since August, when the missed bond payments by the struggling developer Country Garden revealed the severity of a liquidity crisis in China’s property sector. Yet, not all analysts cited seemed to accept such conclusions. “It’s so counterintuitive – the data is getting better and the general environment should be quite positive for Chinese stocks,” said Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at Natixis. “Frankly there’s no reason for this other than investors basically giving up and saying: ‘We don’t see the upside’.”

But why should investor perception be so badly misaligned with realities and with their stated objectives to make money for their investors?

International negative amplification

China’s property market is ailing. That’s typical of rapid industrialization and the associated overhang. What makes it unique is the country’s huge size. Yet, housing demand will prevail. In China, there are now over 400 million people in the middle-income bracket, but the number is expected to reach 800 million in the next decade. As they leave the countryside to the city, they will need homes.

In the past 2 years, Chinese property sales dropped by 10-15%. In 2024, that figure will shrink to 5%. The good news for China’s property developers is that a bottom is in sight, as S&P Global reported already last October. The bad news is that it will take a while for the sector to normalize.

If China is moving toward a soft rebound, why do international media and observers continue to see the glass half empty?

In part, this reflects the kind of negative amplification mechanisms that in the US media contributed to the severity of the 2008/9 Great Recession, as the Nobel-awarded economist Robert Shiller has demonstrated. In the past decades, these mechanisms have accelerated, due to the rise and spread of online media. Furthermore, the increasing weaponization of (even reputable) international media has dramatically proliferated since 9/11, and today it can be leveraged worldwide.

Short sellers for regime change

Obviously, there are fundamental drivers behind the ailing markets in East Asia as well. Nonetheless, a great number of anomalies – economic vibrancy penalized by markets – suggests that there is more to the story. In 2021, short-sellers still won big in the US and even in 2022 as the broader market declined, tallying $300 billion in mark-to-market profits on average short interest of $973 billion.

However, with the end of the quarantines, short sellers lost $178 billion in 2023. What to do? Well, when things get better in the US, short-sellers have been shorting in Asia; foreign markets, companies and currencies, even engaging in regime change.

Last summer, Hong Kong’s financial chief Paul Chan blamed “misunderstandings caused by Western political prejudices” for the stock market’s poor performance, as geopolitical tensions between Beijing and Washington hit a low point.

Ever since the 2011, the West’s geopolitics is driving economies and markets. Unlike economic performance, its impact is unwarranted, adverse and negative. Financial bubbles burst, but geopolitical ploys devastate.

The original version was published by China-US Focus on Jan. 26, 2024