A Call To Free Julian Assange On The 10th Anniversary Of WikiLeaks’ Release Of The Guantánamo Files – OpEd

Ten years ago today, I was working with WikiLeaks as a media partner — working with the Washington Post, McClatchy Newspapers, the Daily Telegraph, Der Spiegel, Le Monde, El Pais, Aftonbladet, La Repubblica and L’Espresso — on the release of “The Guantánamo Files,” classified military documents from Guantánamo that were the last of the major leaks of classified US government documents by Chelsea Manning, following the releases in 2010 of the “Collateral Murder” video, the Afghan and Iraq war logs, and the Cablegate releases.

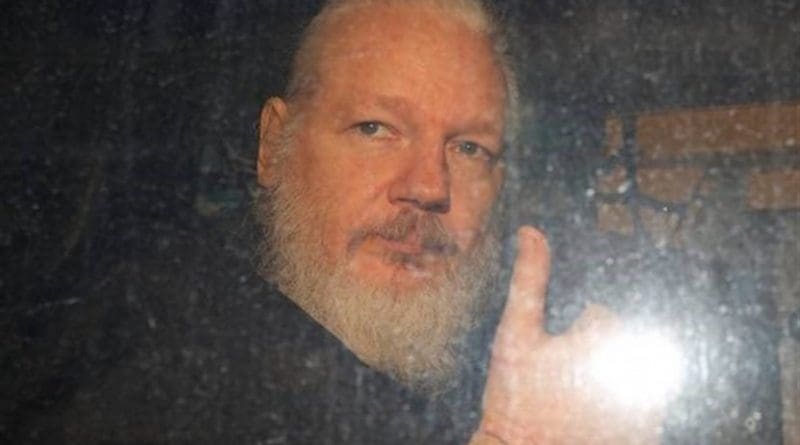

All the journalists and publishers involved are at liberty to continue their work — and even Chelsea Manning, given a 35-year sentence after a trial in 2013, was freed after President Obama commuted her sentence just before leaving office — and yet Julian Assange remains imprisoned in HMP Belmarsh, a maximum-security prison in south east London, even though, in January, Judge Vanessa Baraitser, the British judge presiding over hearings regarding his proposed extradition to the US, prevented his extradition on the basis that, given the state of his mental health, and the oppressive brutality of US supermax prisons, the US would be unable to prevent him committing suicide if he were to be extradited.

That ought to have been the end of the story, but instead of being freed to be reunited with his partner Stella Moris, and his two young sons, Judge Baraitser refused to grant him bail, and the US refused to drop their extradition request, announcing that they would appeal, and continuing to do so despite Joe Biden being inaugurated as president. This is a black mark against Biden, whose administration should have concluded, as the Obama administration did (when he was Vice President), that it was impossible to prosecute Assange without fatally undermining press freedom. As Trevor Timm of the Freedom of the Press Foundation stated in April 2019, “Despite Barack Obama’s extremely disappointing record on press freedom, his justice department ultimately ended up making the right call when they decided that it was too dangerous to prosecute WikiLeaks without putting news organizations such as the New York Times and the Guardian at risk.”

The WikiLeaks revelations

All of the documents leaked by Chelsea Manning and released by Wikileaks in 2010 and 2011 were a revelation. The “Collateral Murder” video, with its footage of the crew of a US Apache helicopter killing eleven unarmed civilians in Iraq in July 2007, including two people working for Reuters, provided clear evidence of war crimes, as did the Afghan and Iraq war logs, as the journalist Patrick Cockburn explained in a statement he made during Assange’s extradition hearings last September, and as numerous other sources have confirmed. The diplomatic cables were also full of astonishing revelations about the conduct of US foreign policy, while “The Guantánamo Files,” as I explained at the time of their release, provide “the anatomy of a colossal crime perpetrated by the US government on 779 prisoners who, for the most part, are not and never have been the terrorists the government would like us to believe they are.”

Publication of the files, which had originally been intended to be sometime in May 2011, had suddenly been brought forward because WikiLeaks had heard that the Guardian and the New York Times, previous media partners of WikiLeaks, who had fallen out with Assange, and who had obtained the files by other means, were planning to publish them, and so, over the course of several hours on the evening of April 24, 2011, I wrote an introduction to the files that accompanied the launch of their publication.

With hindsight, that article, WikiLeaks Reveals Secret Guantánamo Files, Exposes Detention Policy as a Construct of Lies, was one of the most significant articles I’ve ever written, as it summed up why the files — covering 759 of the 779 men held by the US military since the prison opened on January 11, 2002 — were so important, most significantly because they provided the names of those who made false or dubious allegations against their fellow prisoners, revealing the extent to which unreliable witnesses were relied upon by the US to justify holding men at Guantánamo who were either innocent, and were seized by mistake, or were simply foot soldiers, with no command responsibility whatsoever.

The files also revealed threat assessments, which were fundamentally exaggerated. Because no one in the US military or the intelligence services wanted to admit to mistakes having been made, prisoners who posed no risk whatsoever were described as ”low risk,” and, by extension, “low risk” prisoners were labeled “medium risk,” while “medium risk” prisoners — and the handful of prisoners who could perhaps genuinely be described as “high risk” — were all lumped together as “high risk.”

The files also provided risk assessments based on prisoners’ behavior since their arrival at Guantánamo, establishing that many men were held (and some still are) not because of anything they did before they were seized, but because of their resistance to their brutal and unjust treatment in Guantánamo. Also included were health assessments, establishing that even the US authorities acknowledged that, as the Guardian described it, “[a]lmost 100 Guantánamo prisoners were classified … as having psychiatric illnesses including severe depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.”

Unfortunately, within a week of the release of “The Guantánamo Files,” the Obama administration decided that it was imperative to kill Osama bin Laden in a Wild West raid on the compound where he had been living in Pakistan, a move whose timing was, to put it mildly, suspicious, especially as, immediately afterwards, dark forces within the US started promoting the completely untrue notion that it was torture in the CIA’s “black site” program — and the existence of Guantánamo — that had led to the US locating bin Laden.

Following the release of “The Guantánamo Files,” I spent the rest of 2011 largely engaged in a detailed analysis of the files, writing 422 prisoner profiles in 34 articles, in which I dissected the information in those prisoners’ files, demonstrating why, in most cases, it was so fundamentally unreliable. It was a process similar to what I had done in 2006, when I had been the only person to conduct a detailed analysis of 8,000 pages of documents released by the Pentagon after losing a Freedom of Information lawsuit, for my book The Guantánamo Files — and much of my subsequent work — and I remain very proud of my analysis of the files released by WikiLeaks, and am only disappointed that, through a combination of exhaustion and a lack of funding, I was unable to complete my analysis.

I hope, however, that what I completed helps not only to expose the colossal injustice of Guantánamo, but also more than justifies the leak of the documents, for which, shamefully, Julian Assange is still being persecuted.