How Reform Can Aid Growth And Green Transition In Developing Economies – Analysis

By Christian Ebeke and Florence Jaumotte

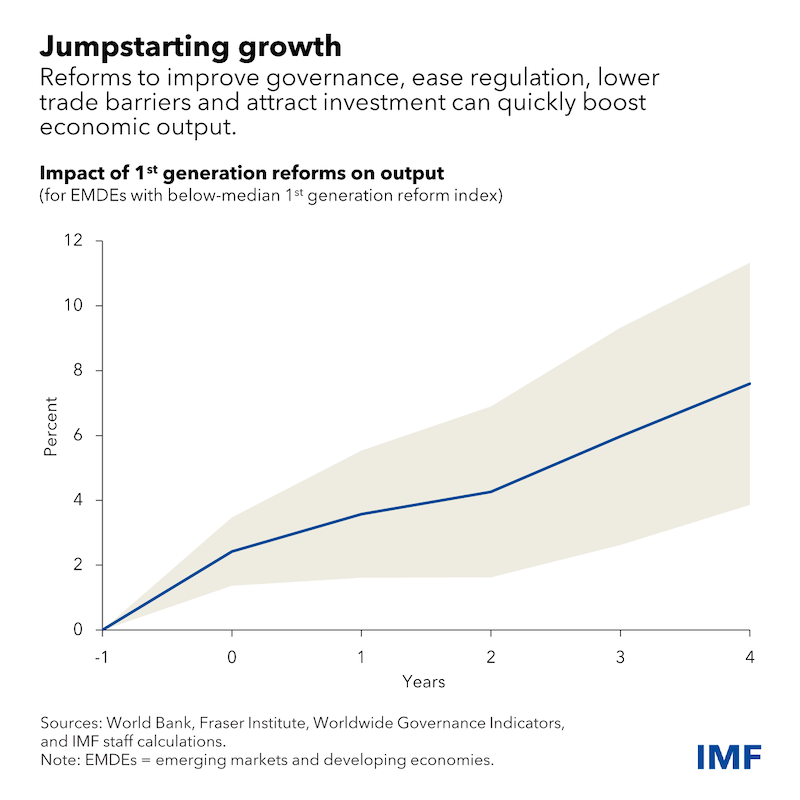

New approaches to governance, business regulation, and trade can boost output by 4 percent in two years and help countries curb emissions

Many emerging market and developing economies face threats to economic growth and limited policy space due to high inflation, rising debt, and balance of payments pressures. These challenges mounted during the pandemic and were further intensified by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Slower growth and constrained capacity to support their most vulnerable people expose some of these countries to substantial social instability risks. At the same time, these economies face the conundrum of participating in global efforts to reduce their carbon emissions and help combat climate change without sacrificing growth and jobs.

Amid such challenges, economy-wide reforms give policymakers the tools to foster growth and prepare for the green transition. As we show in a new staff discussion note, the gains from overhauling institutions and regulations for businesses and people—an enduring IMF recommendation for spurring growth—can quickly materialize even under severe economic strains, provided reforms are properly prioritized and sequenced. And these reforms are key to facilitate the decarbonization of economies.

Rapid output gains

Significant structural impediments continue to hinder growth in emerging market and developing economies. These stem from a range of issues, including weak governance, due to government ineffectiveness, political instability, and corruption. Reducing excessive regulation to make it easier for people to open and run a business is also one area with substantial room for improvement, particularly in low-income countries.

Limits on trade, notably through controls on foreign exchange, and to access to foreign capital are still prevalent in many countries. Additionally, restrictions in credit markets and labor markets contribute to these structural obstacles.

Our research shows that success hinges on how reforms are prioritized, sequenced, and bundled. Major changes addressing critical constraints to economic activity, such as reforms to improve governance and business regulation, and to reduce restrictions to trade and access to foreign capital, can deliver rapid output gains by promoting domestic and foreign investment and enhancing labor productivity. In economies with significant structural impediments, these so-called first-generation reforms can boost output levels by up to 4 percent in two years and up to 8 percent in four years.

Historical examples, such as Georgia’s business regulation streamlining and fiscal reform in 2005 and Senegal ’s comprehensive overhauls to improve governance, business regulation and external integration put in place in 2014-18, demonstrate the growth effects of such reforms. By frontloading these gains, well-designed reform packages could help overcome resistance to major changes and garner public support, including for the green transition.

Decarbonizing the economy

Given the extensive development needs of emerging market and developing economies, it is crucial that decarbonization efforts be accompanied by sustained economic growth.

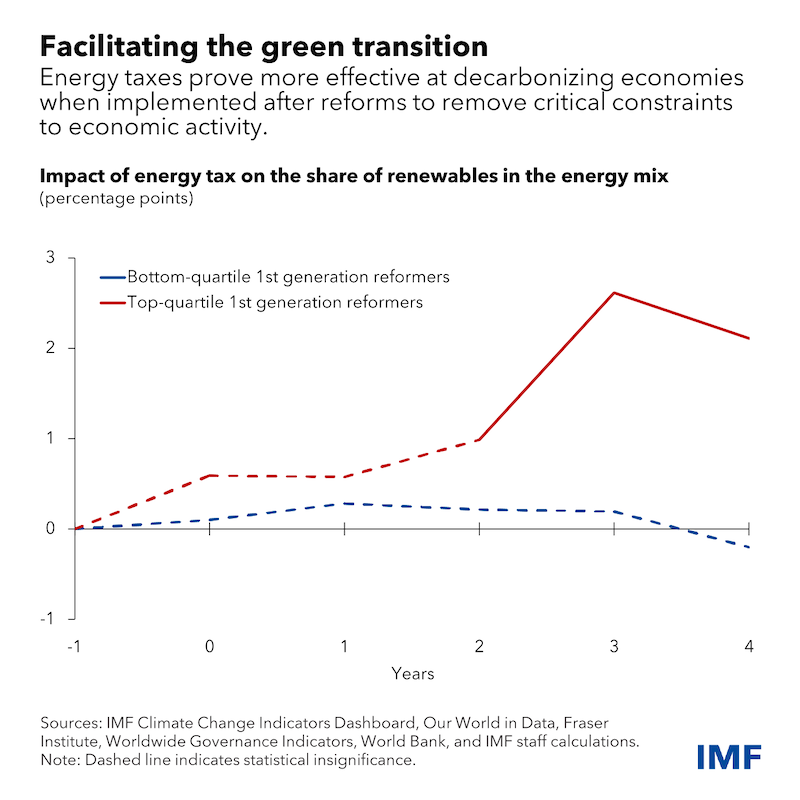

The first-generation reforms are essential to generate growth and thereby support the green transition but also for facilitating the shift to low-carbon activities. Our research indicates that green policies, especially energy taxation, better decarbonize economies after first-generation broad reforms that make the economy more responsive to price signals.

Governance reforms can give the private sector more reason to steer capital toward green investments if they make government policy more predictable and signal that the authorities are more likely to follow through on the policy path that they have charted. They can also reduce implementation risks for climate projects, potentially attracting more financing from abroad. Reducing barriers to creating businesses will enable the private sector to invest more easily in new, green, emerging sectors. Lowering trade barriers can expand access to low-carbon technology and facilitate technology transfers that are critical for the green transition in less technologically advanced countries.

Nevertheless, first-generation reforms alone are not enough to support the green transition. Faster economic growth resulting from these reforms can increase emissions. While growth is essential, emerging market and developing economies must also reduce their carbon emissions over time.

Our research underscores that stringent green reforms, such as energy taxation, regulations, and green investments, are necessary to significantly reduce the emission intensity of economic activity. Combining first-generation and green reforms will enable these economies to reduce their overall emissions while supporting growth.

—This article reflects research by Nina Budina, senior economist, European Department; Christian Ebeke, deputy division chief, Strategy, Review, and Policy Department; Florence Jaumotte, division chief, Research Department; Andrea Medici, research assistant, Research Department; Augustus Panton, economist, Research Department; Marina M. Tavares, economist, Research Department, and Bella Yao, research assistant, Strategy, Review, and Policy Department.

About the authors:

- Christian Ebeke, A national of Cameroon, Christian Ebeke is Deputy Division Chief of the Macro-policy Division at the IMF, where he has led work on geoeconomic fragmentation, macrostructural reforms, and industrial policy, among other assignments.

- Florence Jaumotte is Division Chief of the Structural and Climate Policies Division in the IMF Research Department. She has also worked in the Multilateral Surveillance Division and the World Economic Studies Division of the department, on a number of IMF country teams, and at the OECD in Paris.

Source: This article was published by IMF Blog