‘For As Long As It Takes’: Putting US Aid To Ukraine Into Perspective – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Walter Landgraf

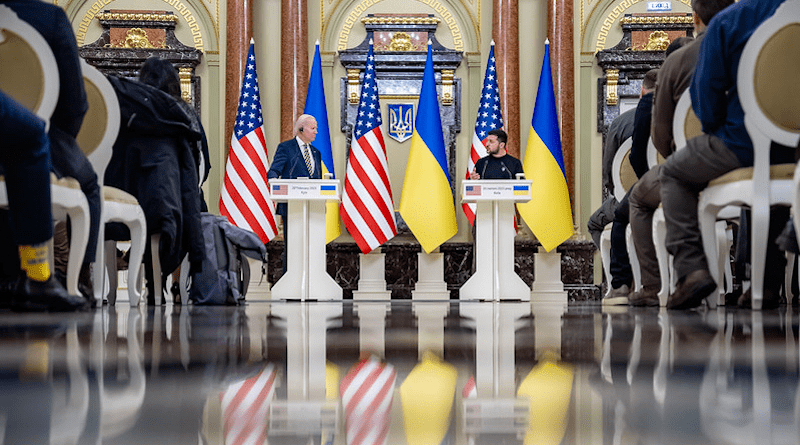

(FPRI) — Over the past year, Biden administration officials from the president down have repeatedly insisted that the United States will continue supporting Ukraine against Russia’s invasion “for as long as it takes.” Secretary of State Anthony Blinken reportedly told his Russian counterpart as much during a meeting on the margins of the March G20 foreign ministers’ summit in New Delhi.

Likewise, on the thirty-second anniversary of Ukraine’s independence on August 24, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin made the same pledge through a press release. On September 21, President Joe Biden himself hosted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House, when he guaranteed future US military aid. In an October 2 conference call with the leaders of the G7 countries, the European Union, and NATO, Biden reiterated that US assistance will continue uninterrupted. This was despite Congress’s September 30 passage of a forty-five-day stopgap funding bill that did not include any new aid to Ukraine due to, among other things, strong opposition from some Republicans.

Commitment and Reputation

In international politics, such assertions amount to a commitment. This refers to the act of pledging oneself to a course of action, and thus surrendering some control over one’s future behavior. When US officials speak publicly about supporting Ukraine “for as long as it takes,” it can put important qualities such as honor and self-respect on the line—as well as America’s reputation for keeping promises.

The notion of reputation as an influential component of international politics is a matter of scholarly debate. Some claim that states which have honored their commitments in the past are more likely to attract allies in the future. Others argue that altering reputations is difficult in the eyes of a state’s friends and enemies because these reputations are embedded in the identities states have already given each other. Irrespective of this debate, the “for as long as it takes” mantra is effectively, and likely purposefully, ambiguous, as it can be interpreted in multiple ways and therefore affords a measure of flexibility in making future moves.

The Power of Material Support

Apart from the obvious goal of enhancing Ukraine’s ability to defend itself against Russia, US material support is meant to reinforce the vocal support as a tangible sign of commitment. Indeed, the vast amount of weapons, equipment, training, and money brings a necessary punch alongside such pledges.

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, the United States stands out as the largest single-country donor to Ukraine. As of Zelensky’s latest visit to Washington in September 2023, the United States has given more than $75 billion in direct aid. This figure does not include an additional $38 billion in war-related funding that did not flow directly to Ukraine, but instead went to various other expenses. For example, almost $17 billion was set aside to fund US European Command operations. Nonetheless, Congress approved four rounds of funding in 2022, bringing the total US commitment to Ukraine to $113 billion.

About two-thirds of the US direct aid has been in the form of total military aid, amounting to $46.6 billion. The biggest chunk of such aid has been in non-financial transfers, such as in-kind donations of weapons and equipment from existing stockpiles, provided through the Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA), whose estimated value is $23.5 billion. The PDA mechanism authorizes the president to quickly withdraw defense articles from Department of Defense stocks, rather than be provided through new sales. It is generally the fastest way to deliver military assistance in a crisis scenario since the Defense Department already has the equipment available. Since August 2021, some six months before the full-scale invasion, the Biden administration has used PDA forty-four times for Ukraine, enabling the swift transfer of all sorts of hardware, from surveillance drones to 155mm Howitzers to night-vision devices. This has enabled Ukrainian forces to rapidly employ US weapons and hardware on the battlefield against Russia.

That Ukraine has received large amounts of aid through Defense Department stockpiles is nearly unique, with Taiwan and Israel being the only other current recipients. In late July 2023, the Biden administration announced it was sending $345 million of military aid to Taiwan. This was the first time that PDA was used with the country, possibly suggesting the beginning of a new dimension in bilateral relations, while simultaneously signaling US resoluteness against China. After the Hamas attack on Israel, the White House announced it would also use PDA to support Israel’s defense needs.

Other US military aid to Ukraine has involved security assistance as well as grants and loans for purchasing weapons and equipment, amounting to $18.3 billion and $4.7 billion, respectively. Security assistance comprises, among other things, training, logistics, and intelligence support, provided through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative. The initiative is a Defense Department-led funding program, tying such aid to the condition of Ukrainian progress on defense reforms, according to the US Embassy in Kyiv. Another mechanism, the Foreign Military Financing Program, exists primarily to fund equipment sales, offering grants and loans to help allies and partners buy weapons and kit produced in the United States.

In addition, the United States has given Ukraine $26.4 billion, roughly one-third of total direct aid, in financial assistance through, among other ways, the Economic Support Fund, a State Department-managed account meant to advance US foreign policy goals.

Finally, the United States has sent $3.9 billion in humanitarian aid, providing emergency food assistance, health care, and refugee support. Undoubtedly, the war in Ukraine has been a humanitarian catastrophe. Due to intense fighting and deliberate targeting of Ukrainian civilians, an estimated 5.1 million people have been driven from their homes and are internally displaced. Another 6.2 million people have crossed into neighboring countries or beyond. Eastern European countries, particularly Poland, have welcomed the greatest number of Ukrainian refugees.

Understanding Ukraine Aid in a Larger Context

Despite the staggering amount of aid committed, in the bigger picture, US support for Ukraine thus far has been rather limited. A research team from the Germany-based Kiel Institute for the World Economy has been tracking international aid to Ukraine since January 24, 2022, the day when several NATO members put their forces on alert. They have found that Europe has clearly overtaken the United States in promised aid to Ukraine as of September 2023, with total European commitments now twice as large. All told, the Kiel Institute’s “Ukraine Support Tracker” lists a total of approximately $164 billion in European aid. This includes substantial commitments from non-EU countries such as Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Crucially, some European pledges involve multi-year packages, unlike US aid, bringing a degree of predictability in future external support to Ukraine.

From a historical perspective, US aid to Ukraine is relatively small compared to the cost of some past wars. This includes foreign military aid during World War II and the Spanish Civil War, as well as US military expenditures in the Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq wars. When measured in percent of donor GDP, the support of Eastern European countries to Ukraine has been particularly generous, especially when considering the cost of hosting Ukrainian refugees. The Baltic states, Poland, and Bulgaria, but also the United States, are among the top ten donors as a share of donor GDP. Although smaller than some past wars and smaller than overall European commitments, US aid to Ukraine is nevertheless substantial in both absolute and relative terms, indicating the Biden administration’s deep commitment to Ukraine so far.

The Road Ahead

While US aid has enhanced Ukraine’s ability to fend off Russia’s invasion, future financial, military, and humanitarian assistance may be in doubt. On October 3, the House of Representatives voted to remove Kevin McCarthy as House speaker. With the House leaderless, there was no legislation. This had serious implications for Ukraine. Among international donors, the United States is a unique case, as it can only provide aid overseas through an act of Congress. For Ukraine, this has resulted in four pieces of legislation, all passed in 2022. Indeed, part of the reason the United States is now lagging behind Europe in commitments is because Congress has not made any new meaningful pledges in 2023. Any future legislation will depend on the backing of House Republicans—some of whom have argued that money for Ukraine would be better spent on domestic priorities, such as border control—led by Rep. Mike Johnson, who was just elected speaker of the House on October 25. Furthermore, US public support for Ukraine aid has been waning. Most Americans oppose Congress providing additional funding, according to a July 2023 poll conducted by SSRS, a Pennsylvania-based research firm.

A dramatic drop or end to US aid might have far-reaching consequences. In military terms, it could change the course of the war by weakening Ukraine’s warfighting capability, leaving it depleted against Russian offensives and probably incapable of taking decisive action to break through Russian defenses and regain lost territory. Without the backing of one of Ukraine’s most ardent Western supporters, Europe would be forced to step up even more. Transatlantic political solidarity and resoluteness against Russia could fracture because of the loss of US aid. Such an outcome might also affect US credibility, as reneging on a commitment can damage a country’s reputation for reliability because it risks the dismissal of future commitments as mere “cheap talk.” On the other hand, perceptions of reputation, whether “good” or “bad,” are a matter of interpretation. Like identities, they can be fluid and changeable. This helps to explain, in part, how West Germany, the former enemy state shorn of its eastern territories, became a staunch military ally of many of the countries that had been fighting against it a decade previously, through its 1955 accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Despite the exhortations that the United States will support Ukraine’s fight against Russia “for as long as it takes,” the Biden administration alone cannot guarantee this. It will have to continue working to convince both Congress and the American public that assisting Ukraine enhances US national security. The task of securing future aid to Ukraine will likely become harder as the 2024 presidential election comes into focus. The Biden administration will be forced to balance international commitments with domestic imperatives. In an already polarized political environment, the road ahead is bound to be bumpy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

About the author: Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Walter “Rick” Landgraf is a United States Army officer and Fellow in the Eurasia Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Source: This article was published by FPRI