The Arduous Journey Of Girls’ Education In Afghanistan – OpEd

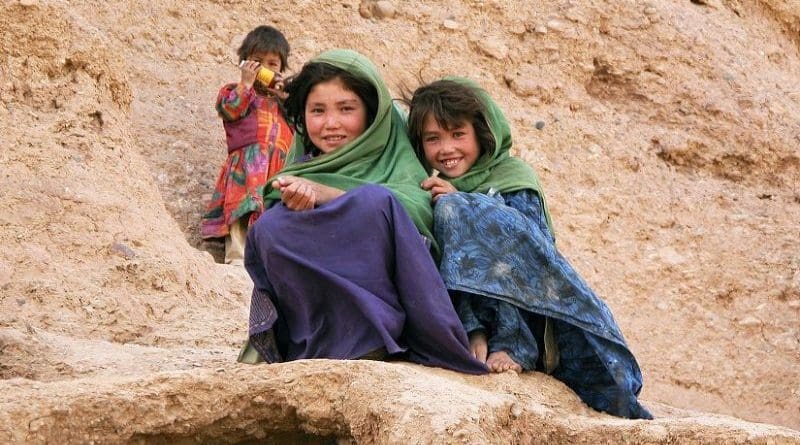

Throughout the Afghan history, Afghan women had struggled from the harm and suffocation created by politicians, and the conservative mindset of the tribal and religious leaders throughout the history. Although the topic of Afghan women became the center of attention of international community during the Taliban regime and was one of the justifications for the Western military’s invasion in the country, the current status of Afghan women is not only the result of Taliban politics. There is a long history of subjugation since the foundation of modern Afghanistan.

After the collapse of the Taliban, women empowerment and girls’ education was highlighted by the international community and the government as a success story of their projects. But today after almost two decades, only 37% of adolescent girls are educated compared to 66% of adolescent boys. The statistics from 2017 shows that the rate of school-going girls in the country has decreased by 2% compared to 2008, where according to Afghan Ministry of Education, only 39% of students were female (Alvi‐Aziz, 2008). Reportedly, Afghanistan has 15,249 government school with almost 8.7 million students enrolled. The expansion has included girls, who previously were almost completely prevented from attending school under the Taliban.

Meanwhile, in 2015, Afghanistan’s Ministry of Education reported that the annual number of secondary graduates had risen from about 10,000 in 2001 to more than 266,000 in 2013 and was estimated to reach 320,000 in 2015. A World Bank report from 2017 states that girls’ education in Afghanistan vary based on province and geographical area, as there are certain provinces that will achieve gender equality in primary school education in the next five years; while in some other provinces as Paktika, girls school attendance has declined to 35 percent in 2013-14.

Historically, women’s education has been constrained by different practices and ideologies depending on the era and political situation. With the foundation of modern Afghanistan by Abdur Rahman Khan in 1880 up to the Soviet occupation in 1979 that led the country to decades of long war, the country had gradual improvements in attending to women rights.

Women’s status drastically changed during Amanullah khan era (1919–1929). Attempting to transform Afghanistan into a modern state, alongside other changes, he emphasized a secular base education, which was considered a big move in the era of madrassas (Islamic religious schools). Amanullah Khan established the first primary school for girls in Kabul in 1921. Education programs were promoted all over the country, and as an effort to encourage the education of women, fifteen middle-school girls were sent abroad for higher education. After Amanullah khan until the establishment of the communist government, Afghan women had slow and steady progress in terms of gaining access to education; policies related to education and women right enhanced and more schools opened for girls all over the country (Samady, 2001).

With the withdrawal of Soviets in 1988 and the beginning of civil war, Afghanistan lost its basic infrastructure and the educational personnel; through this process the educational system also destroyed. This drastically impacted male and female education all over the country. In general, civil wars impact education in two ways: it impacts the educational expenditure, where the government lose the capacity of providing educational services to the people or it affects the rate of school’s enrollment by the physical destruction of schools, closure of school in terms of safety and displacement of the students. In the case of Afghanistan, prior to Taliban regime, the civil war has severely destroyed all the infrastructures, including school facilities.

In 1992, women were increasingly precluded from public service. In conservative areas in 1994, many women appear in public only if dressed in a complete head-to-toe garment with a mesh covered opening for their eyes. Mujahedeen entered Kabul and burned down the university, library and schools. Women were forced to wear the burqa, and fewer women were visible on television and in professional jobs.

In 1994, Taliban completely took over the country and enacted extreme and severe law for women, which they justified with the claim that Islam orders such measures. The gender policies of the Taliban included “forbidding women to work outside of the home, requiring women to wear a head-to-toe covering, when they venture out into public, forbidding girls from attending school, preventing women from going out in public unless accompanied by a close male family member. As the result of deprivation from education and the society, Afghanistan became the country with the highest rate of female illiteracy in South Asia. As Aforesaid, not only Taliban’s but the policies and restrictions imposed by different political regimes throughout the history, has impacted the status of Afghan women education.

A report by ONE international organization asserts that Afghanistan is one of the 10 worst nations in the world for girls to get education. In addition, the country in 2014 had the highest gender disparity in primary schools, where for every 100 boys in primary schools, there were only 71 girls (Mellen, 2017). While, girls’ education is considered a vital issue by the Afghan government and its international allies; projects worth million dollars has been implemented to address the issue of gender disparities in education.

In addition to civil conflict, the main impediments to girl’s education include cultural influence, social and economic constraints, and insecurity, which are huge issues not only for Afghans but for all developing countries. The extent of these barriers, however, vary from province to province.

Cultural barriers

The main constraint for women’s education from establishment of modern Afghanistan until the withdrawal of the Soviet Union in 1989, was the cultural and religious beliefs of people that were preventing women from stepping out of the house for educational and professional proposes (Alat, 2006). Girls’ education has struggled form tribal prominence in the country with tribal and Islamic law taking precedent over the legal constitution in deciding gender roles. Huma Ahmed-Ghosh stated that the “Tribal power plays, institutions of honor, and inter-tribal shows of patriarchal control have put women’s position in jeopardy… The honor of the family, the tribe, and ultimately the nation is invested in women” (2003, p. 3).

Harmful gender norms prohibiting girl’s education, that have been practiced for generations by Afghans, have created an undesirable and unnecessary practice in most parts of the country. The patriarchal conservative traditions are mostly influenced by religious and tribal values by people which form the bulk of the Afghan society (Samady, 2001). Afghan culture has defined almost all aspects of a woman’s life, adherence to which will protect the reputation, honor and dignity of a woman, her family and relatives. Religious schools (Madrassa) are still preferred by families in rural areas, which contain the majority of Afghanistan. While boys are sent to Madrassas, girls are taught Islamic studies by the elders of the family at home, in order to prevent girls from leaving the family home (Daniel, 2001).

Furthermore, early marriages of girls are another cultural barrier that negatively impacts girls’ education in Afghanistan. According to Human Rights Watch, a third of Afghan girls marry before age 18, which not only results in school droppage but also include serious health risks for girls. Meanwhile, statistics illustrate that conservative mindset is not the only burden on the way of women education in developing countries, but security and economy also play key role in this field.

Economic Constraints

Although, the Afghan government provides free education for people throughout the country, poverty is still a big obstacle for children’s education especially in rural areas and among girl students. A Human Rights Watch report asserted that at least a quarter of Afghan children between ages 5 and 14 work for a living or to help their families, including 27 percent of 5 to 11-year-olds. Girls are most likely to work in carpet weaving or tailoring, but a significant number also engage in street work such as begging or selling small items on the street.

Families with socio-economic constraints usually prioritize boys’ education more than girls’ education. In addition to poverty among families, the limited investment of government on educational resources in insecure and remote provinces, also has direct impacts on the number of school-going girls since, the number of female teachers and school buildings play key roles in the decision of families about sending their daughters to school.

Insecurity

In societies recovering from conflict, female student still experiences high level of violence and insecurity not only form the society but also from the government oppositions that try to prove their existence and power to the people and government.

Although, schools’ doors have been opened to Afghan girls, the offensive operations by insurgent groups led by Taliban in some provinces is still a big constraint that deters girls from going to school. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) in 2018, asserted that the ongoing conflict and worsening security situation across the country combined withdeeply engrained poverty and discrimination against girls have pushed the rate of out ofschool children up for the first time since 2002 levels. Attacking girls ‘schools or burning schools is a common strategy of insurgent groups to warn families to not send their daughters to school.

These attacks have had devastative consequences both on schools’ operation and girls’ school attendance. CNN report stated that in 2015 alone 185 attacks on girls’ school had been documented, where the majority of attacks were attributed to armed groups with girls’ education.

*Neela Hassan, Journalist and MA of Communication for Development studies from Ohio University, the U.S

References

- Alvi‐Aziz, H. (2008). A progress report on women’s education in post‐Taliban Afghanistan. International Journal of lifelong education, 27(2), 169-178.

- Samady, S. R. (2001). Education and Afghan society in the twentieth century. Afghan Digital Libraries.

- Mellen, Ruby. (2017). Afghanistan Ranks Among the Worst Places for Girls to Get an Education. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/10/17/afghanistan-ranks-worst-places-girls to-get-an-education-africa/

- Alat, Z. (2006). News Coverage of Violence against Women. Feminist Media Studies, 6(3), 295–314.doi:10.1080/14680770600802041

- Daniel, John. (2001). Education and Afghan Society in the Twentieth Century. Relief Web. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/education-and-afghan-society-twentieth-century