Ethics Of Existential Militancy – OpEd

By Yanis Iqbal

The present-day conjuncture of neoliberalism is characterized by the mass psychology of individualism. No matter what happens to the large swathes of humanity that are being tortured by the dehumanizing effects of abject poverty, we remain unbothered, ensconced in our own private fantasies of security and certainty. Every event of structural cruelty is perceived as a disconnected capsule of historical time that can’t possibly affect the concrete happenings of one’s own life.

This sense of apathy is indicative of the deeper inability to think in terms of totality, to conceptualize the society as an interconnected whole that has a formative impact on the individual. In the absence of this capacity to form contextualizing reasons, human subjectivity becomes beholden to passivity. Instead of problematizing obstacles and crisis with a view to overcome or resolve them, we try to come up with different ways and means of coming to terms with them. In this way, the normal state of affairs becomes a terrifying one, constantly confronting us with the problem of how to cope with massive structures.

The overwhelming oppressiveness of social architectures – their spectral independence from the direction of individual wills – demands that we constantly weave images of stability that provide us with a general orientation amid the chaos of individual powerlessness. And this subjective imperative provides a suitable climate for the growth of neo-fascist ideas, which promise to help the atomized human being gain control over the contingencies of the world.

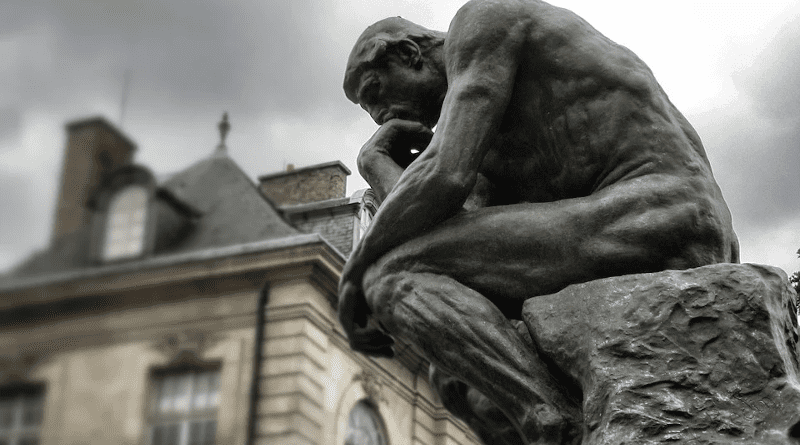

As is clear, contemporary feelings of indifference and impotence stem from the suppression of agency, defined as conscious, goal-directed activity. In refusing to process reality in terms of collective frameworks and deferring our agency to fantasmatic narratives, we decline to come to terms with the fundamental feature of human existence, namely that existence precedes essence. We are, as human beings, thrown into the world. We first of all exist, encountering the world, interacting with its manifold complexity and defining ourselves afterwards.

In the words of Jean-Paul Sartre, “Man simply is. Not that he is simply what he conceives himself to be, but he is what he wills, and as he conceives himself after already existing – as he wills to be after that leap towards existence. Man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself.” This primary emphasis on the existence of the human being means “that man is, before all else, something which propels itself towards a future and is aware that it is doing so. Man is, indeed, a project which possesses a subjective life, instead of being a kind of moss, or a fungus or a cauliflower. Before that projection of the self, nothing exists; not even in the heaven of intelligence: man will only attain existence when he is what he purposes to be.”

Insofar that existence precedes essence and humans have an inherent anti-deterministic quality of spontaneity to their lives, “one will never be able to explain one’s action by reference to a given and specific human nature; in other words, there is no determinism – man is free, man is freedom.” “[M]an is condemned to be free. Condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.” Since the being of humanity reality is indistinguishable from this state of freedom, the constitutive aim of human spontaneity should be the expansion of this freedom itself. As Sartre say, “freedom, in respect of concrete circumstances, can have no other end and aim but itself; and when once a man has seen that values depend upon himself, in that state of forsakenness he can will only one thing, and that is freedom as the foundation of all values.” This means that humans should construct social systems that allow them to freely engage in objectification i.e. the consciously regulated production of things and the production of oneself as subject that results in the generation of material cultures that convey our efforts to remake the world in our own image.

Capitalism is a system that tries to limit the self-conscious spontaneity of humanity – and its ability to express itself by objectification – through the construction of reified forms of control. It sets up architectures of alienation that convert objectification into a process of external direction, channeling agency into institutionalized habits that keep repeating themselves. Terry Pinkard notes: “Objectification becomes alienation when it transforms the results of spontaneity into recurrent patterns of behavior (as when the necessity of certain machines in the productive process forces people into a deadening routine).” The regularization of alienating rituals turns objectifying praxis into “praxis-process, a set of actions carried out without the agent being fully self- conscious of what he is doing as a totalization, even if each of the individual actions that are a component of the whole action are known by him”. This reification, however, does not make agents into “things” but rigidifies “actions into set processes and into preset scripts for” agents to enact. “This picture of praxis- process is that of an agent self- consciously dragging himself along the rails that have been laid out in advance for him instead of simply coasting down the rails propelled by his own hexis [acquired dispositions and natural drives]. He is not being pushed, he is pulling himself, but doing it so that he can approximate being pushed.”

Thus, even when we are reified, we don’t lose our agency; we merely accept the deterministic doctrines of capitalism to hide our situation of free choice. The reified individual – as Pinkard comments – takes “a purely exterior, objective view of himself as somebody forced into a prefabricated life, which is an outlook that rests on a peculiar type of “active passivity,” a concerted effort grounded in spontaneity to make oneself into the non- spontaneous creature one takes oneself to be.” Capitalist individuals actively try to become a passive being. “One actively works, that is, at being something one cannot be, namely, something that does not actively work at it.” The continued presence of agency even in our attempts to lose agency provides the objective basis of revolutionary change. Though subalterns exist as passive material for other-direction – trapped either in individual fantasies of neoliberal security or collective fantasies of xenophobic redemption – their passivity is just a symptom of a weak form of agency. This pessimistic agency needs to be revived by the moral radicalism of existential hope that accepts the basic freedom of human agency and promotes the formation of structures suited to the growth of independent human subjectivity. As Sartre aptly remarked, “You are free, therefore choose, that is to say, invent. No rule of general morality can show you what you ought to do: no signs are vouchsafed in this world.”