India And Iran: More Than What Meets The Eye – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

It is in New Delhi’s interests to maintain cordial relations with Iran.

By Ketan Mehta

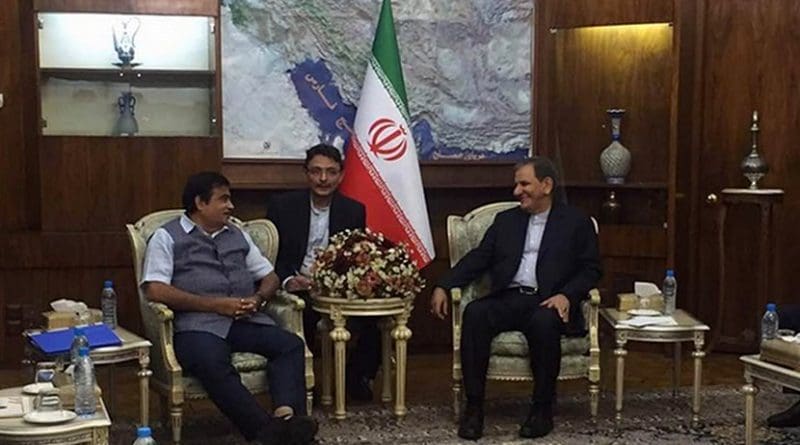

The visit of Minister of Road Transport Highways and Shipping, Nitin Gadkari who as India’s representative attended Hassan Rouhani’s swearing in ceremony signifies the high stakes for New Delhi in Iran where its investments in infrastructure and energy sectors have future implications. The recent India-Iran dispute over the development of the Farzad B gas field and the stagnant trilateral partnership between New Delhi, Tehran and Kabul to balance the rise of China complicates the dynamics of their relationship. In this context, India has to safeguard its own interests in the region and not enrage Iran over the question of its territorial and political sovereignty.

These developments come at a juncture when China’s grand One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative is being welcomed in the region. Nonetheless, two of Asia’s largest ventures in the form of OBOR and India’s trilateral partnership have political, socio-economic, and security ramifications. As partnership with Tehran is crucial for both New Delhi and Beijing, the recent uproar over the development of Farzad B gas field upsetting New Delhi signifies the dynamics of New Delhi-Tehran relations are much more complex than it seems.

Indian demand and Farzad B gas field

With an ever-increasing demand of fuel and having recently ratified the Paris Agreement to cut emissions, gas, which is plentiful in Iran, remains a precious commodity to be secured for India. However, New Delhi a significant consumer of Iranian oil and gas recently locked horns over the Iranian decision to float a tender for developing the Farzad B gas field.

Interestingly, India’s ONGC Videsh Ltd. had discovered the potential of Farzad B gas field in 2009. At that time, India lost interest in the project as Western sanctions made progress difficult. Despite that, New Delhi had continued to buy Iranian oil and pay for it in dollars much to the dismay of Washington. The tightening of sanctions by the Obama administration in 2011 over Tehran’s controversial nuclear programme making investments, and access to international banking a lot harder; which led India to first use Euro and finally Indian Rupee as a mode of payment to facilitate oil imports.

This was evident when Iranian foreign minister Javed Zarif who during his visit to India, acknowledged New Delhi’s support during tumultuous times. Indian interests in the gas field rekindled after Tehran signed the historic nuclear agreement in 2015 with the West, which allowed oil and gas companies to redeem operations.

However, the initial clearance to Russian gas giant Gazprom to develop the gas field suggests that Iran is not ready to extend undue favors to the Indian consortium ONGC-VL, which interestingly also has investments with Gazprom in Russia. Ironically, Gazprom too is in a predicament as the Trump’s administration and US Congress’ new sanctions bill threaten Moscow’s gas exports to Europe. Therefore, it is in India’s best interest to push for the developmental rights for the project at this point of time especially when the Trump administration new sanctions against Tehran, can be quite uncertain in the near future threatening its energy exports. New Delhi’s hardball tactic of reducing oil imports from Iran, which emerged as India’s third largest oil supplier, would only displease Tehran, making future investments difficult.

India’s desperation to keep its energy stake in Iran is evident from the fact that the Indian consortium is willing to invest as much as USD 11 billion in the project. This ambitious push comes at a point where the majority of the oil demand in the world is expected to come from India, according to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). While the demand for gas is likely to go up, India’s import of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) is forecasted to increase to a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 8.92 per cent. The year 2016 was marked by the highest growth rate of fuel sales at 10.7 per cent. This thirst for oil and gas supplies is driven by rapid urbanisation and economic growth, making Iran with second largest proven gas reserves an irreplaceable supply partner.

However, India is not the only one vying for oil and gas in the region. For New Delhi, a part of the Iranian engagement is driven by the Chinese ambition of linking the Mainland with Iran. Contemplating the growing role of China in Pakistan’s strategic Gwadar port, New Delhi responded by emboldening its commitment in the Iranian province of Sistan-Balochistan where India has invested in the Chabahar port project.

Trilateral partnership: Still a long way to go

Keeping a friendly Iran is central to India’s concern in the region. This was expressed by India’s Minister of Road Transport Highways and Shipping, “Chabahar will not only boost ties between Iran and India but we will be closer to Afghanistan and then Russia.. We can export goods till Russia. This will be a direct route.” Having signed the historical tripartite agreement in 2016, which brings Iran, India, and Afghanistan closer by bypassing Islamabad is a move that exemplifies the stretch of geopolitical rivalry between Beijing and New Delhi to increase influence in the region.

The fact that Indian investments in Chabahar are meagre as compared to the mammoth Chinese investments in the Gwadar Port project, New Delhi’s anxiety can be gauged from the fact that it has built the Delaram-Zaranj highway connecting Iran and landlocked Afghanistan. However, keeping the rhetoric aside, Chabahar can never substitute for the geographically gifted Gwadar port, which is a deep-sea port. This is complemented by the fact that Tehran is still awaiting the promised USD 150 million soft loan and the USD 500 million investment in the special economic zone to be developed around Chabahar. And, then a trilateral partnership which New Delhi has long eyed can only be realised when peace and stability is achieved in Afghanistan. Most importantly, the relationship between New Delhi and Iran is not a zero-sum game which can guarantee India a freeway. This is unlike the China-Pakistan equation where Beijing has developed a significantly advantageous relationship with Islamabad.

Then, Iran-China relationship has already advanced to a stage where Beijing is Tehran’s largest trade partner with significant investments in energy sector across Iran. This means that achieving Indian aims in the region are lot harder, especially when Beijing committed to USD 600 billion trade with Iran, a lot more than the latter’s GDP. Then, post sanctions, Chinese exports to Iran will have to compete with others, which was hardly the case during the tumultuous period in 2011. This means that China’s USD 24 billion exports are not going to jump as per Beijing’s expectations which is good news for India-Iran trade.

In all, India-Iranian relations have been pleasant even in times when Tehran was under pressure for pursuing a disruptive foreign policy in the region and running an ambitious nuclear programme. It is in New Delhi’s interests to maintain cordial relations with Iran, keeping in mind Tehran holds the key to energy security, is a gateway to Eurasia, and New Delhi should avoid pressuring Tehran on matters that infringe its sovereignty.

The author is a research intern at Observer Research Foundation New Delhi.