World Needs More Policy Ambition, Private Funds, And Innovation To Meet Climate Goals – Analysis

By Simon Black, Florence Jaumotte and Ananthakrishnan Prasad

With each passing year, the stark reality of a hotter planet becomes clearer and the ensuing risks to the global economy intensify. But as the world is waking up to the scale of the climate crisis, geopolitical tensions and fragmentation risks are undermining our ability to coordinate global actions to solve this planetary problem.

Eight years on from the Paris Agreement, policies remain insufficient to stabilize temperatures and avoid the worst effects of climate change. Collectively, we are not cutting emissions fast enough and are falling short on the needed investment, financing, and technology. The window is closing, but we still have time—just—to change our trajectory and leave a healthy, vibrant, and livable planet to the next generation.

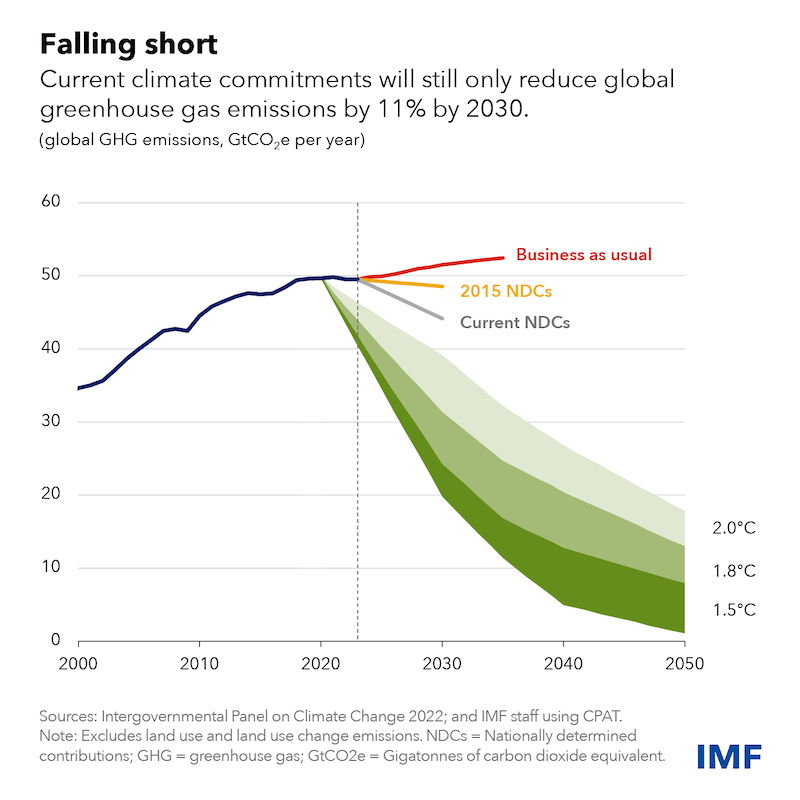

Limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees to 2 degrees Celsius and reaching net zero by 2050 requires cutting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases by 25 percent to 50 percent by 2030 compared with 2019. But, as our new analysis shows, the current global commitments reflected in nationally determined contributions would reduce emissions by just 11 percent by the end of this decade.

To make matters worse, current policies are not consistent with commitments, which means that the world is set to fall short of even that meager goal. Business-as-usual policies would see annual global emissions increase by 4 percent by 2030 and reach a cumulative level sufficient to breach the 1.5-degree target by 2035.

More ambition, stronger policies

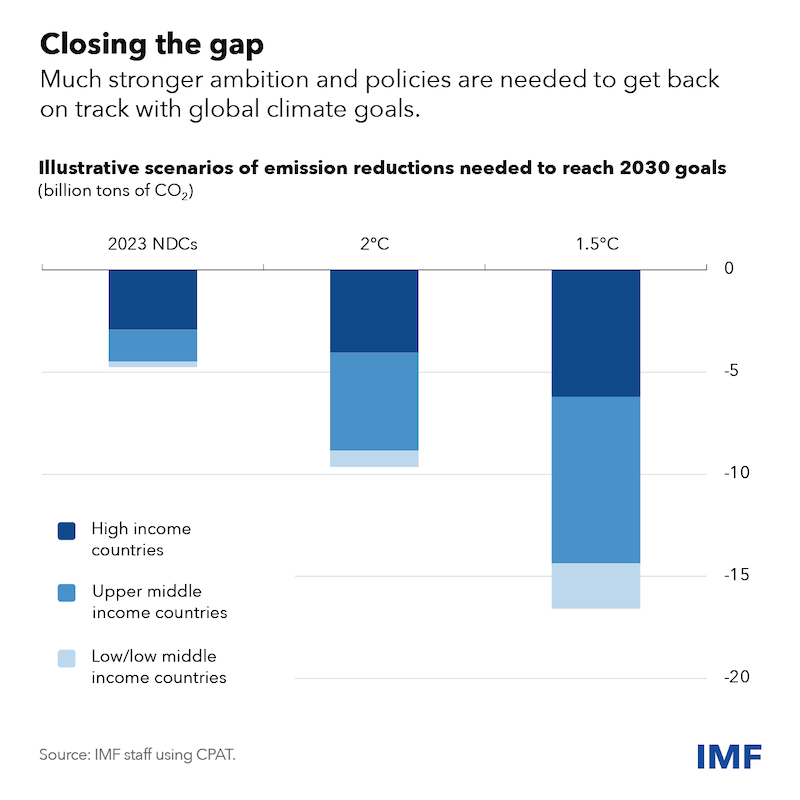

To get back on track with the global climate goals, we need more ambition now. A fair approach is for countries to target cuts in emissions in line with per capita incomes.

For example, to keep within 2 degrees of warming, high, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low-income countries will need emissions reductions of 39 percent, 30 percent, 8 percent and 8 percent, respectively, by 2030. To stay below 1.5 degrees of warming would entail more drastic emissions cuts of 60 percent and 51 percent for high- and upper-middle income countries.

Ambition alone is not enough. We also need major policy changes to achieve these more ambitious targets. These would ideally be centered on a robust carbon price—rising to a global average of at least $85 per ton by 2030—to provide broad incentives to reduce carbon-intensive energy, shift to cleaner sources, and invest in green technologies.

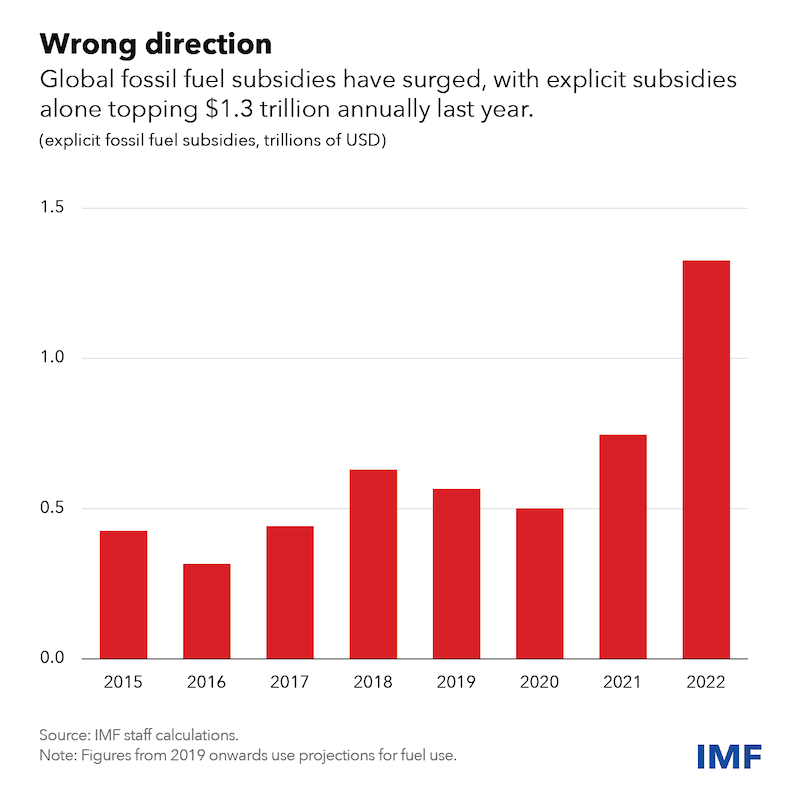

A carbon price also generates more than enough budget revenues to support vulnerable groups. Around 20 percent of carbon pricing revenues can more than compensate the poorest 30 percent of households. This is in direct contrast to damaging fossil fuel subsidies, which have risen to a record $1.3 trillion annually in explicit fiscal costs alone. Countries must act to phase out such subsidies.

At a global level, cooperation is needed to help assuage fears that carbon pricing would hurt national economic competitiveness. Here, an agreement among large emitters could spur other countries to follow—such as a progressive deal between China, the European Union, India, and the United States. This would cover over 60 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and send a strong signal to the rest of the world.

Boosting climate finance

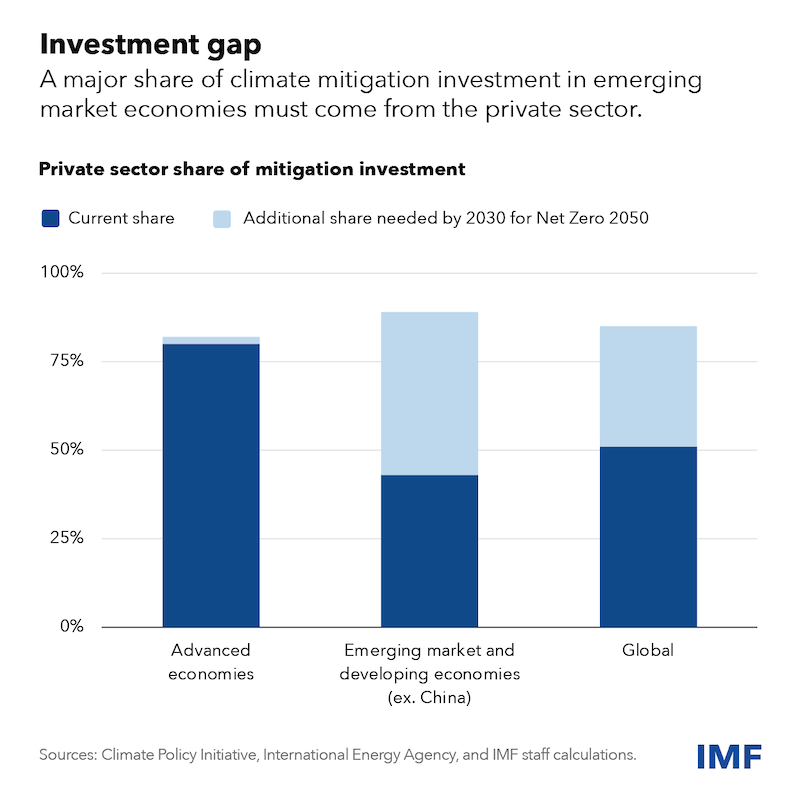

The path to net zero by 2050 requires low-carbon investments to rise from $900 billion in 2020 to $5 trillion annually by 2030. Of this figure, emerging and developing countries (EMDEs) need $2 trillion annually, a fivefold increase from 2020. Even if advanced economies meet or somewhat exceed their promise to provide $100 billion a year, the bulk of the financing for these low-carbon investments will need to come from the private sector.

Our analysis shows that private sector share of climate finance must rise from 40 percent to 90 percent of the total in EMDEs by 2030. That means a broad mix of policies to overcome barriers such as foreign exchange and policy risks, underdeveloped capital markets, and too few investable projects.

For example, targeted economic policies and governance reforms can lower capital costs. Meanwhile, blended finance that combines private capital with public and donor funding—including from multilateral development banks—can bring down the risk profile of green projects. Think of first-loss capital, credit enhancements, or guarantees.

At the same time, global policies to increase transparency and comparability of projects, standardize taxonomies and strengthen climate-related disclosure requirements are vital in helping investors make low-carbon choices. Again, this highlights the importance of international cooperation.

Scaling up innovation

Of the 50 percent cut to emissions needed by 2030 to stay on track for the 1.5-degree target, more than 80 percent can be achieved from technologies available today. Getting to net-zero by 2050 will, however, require technologies that are still under development or yet to be invented.

Unfortunately, patent filings for low-carbon technology peaked at 10 percent of total filings in 2010 and have since declined. Worse, key technologies aren’t spreading fast enough to emerging and developing countries.

How can this trend be reversed? Recent IMF analysis shows climate policies—such as feed-in tariffs and emissions trading schemes—boost green innovation and investment flows,and help spread low carbon technology across borders. Moreover, in some countries, lowering trade barriers can accelerate imports of low carbon technologies by 20 percent to 30 percent. Yet again this points to the importance of cooperation: to avoid protectionist measures that would impede the broader spread of low-carbon technologies.

Helping countries meet goals

Wherever climate policy intersects with macroeconomic policy, the IMF is here to help. Our new Resilience and Sustainability Trust provides long-term financing on affordable terms to help vulnerable middle- and low-income countries cope with threats such as climate change. The $40 billion trust has already supported programs for 11 countries, with twice that number in the pipeline.

For our wider membership, we add a climate lens to our economic analysis, policy advice, capacity development and data provision. Why? Because macroeconomic and financial sector policies are critical to harnessing the opportunities of the green transition: for low-carbon, resilient growth, and jobs.

But no country can tackle climate change on its own. International cooperation is more important than ever. Only with concerted action, now, will we bequeath a healthy planet to our children and grandchildren.

About the authors:

- Simon Black is an Economist at the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department where he specializes in climate change mitigation, carbon pricing, and environmental taxation. Before joining the IMF, he was a Climate Economist at the World Bank, a Climate Economist at the UK’s Foreign & Commonwealth Office, and served on the UK delegation to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) where he helped negotiate the Paris Agreement.

- Florence Jaumotte is Division Chief of the Structural and Climate Policies Division in the IMF Research Department. She has also worked in the Multilateral Surveillance Division and the World Economic Studies Division of the department, on a number of IMF country teams, and at the OECD in Paris. Her research interests include: labor market policies, climate, economic growth, inequality, and open-economy macroeconomics.

- Prasad Ananthakrishnan is the Unit Chief, Climate Finance Policy Unit, in the Monetary and Capital Markets Department (MCM), International Monetary Fund. He heads the IMF Task Force on Climate Finance. Prasad has led Financial Sector Assessment Program missions to Germany (2022), Hong Kong SAR (2020) and Peru (2017) and participated in the Indonesia FSAP (2016). He also headed the Strategy and Planning Unit (MCM) between 2018-April 2022.

Source: This article was published by IMF Blog