The Fiscal And Financial Risks Of A High-Debt, Slow-Growth World – Analysis

By Tobias Adrian, Vitor Gaspar and Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas

Inflation-adjusted interest rates are well above post global financial crisis lows, while medium-term growth remains weak. Persistently higher interest rates raise the cost of servicing debt, adding to fiscal pressures and posing risks to financial stability. Decisive and credible fiscal action that gradually brings global debt levels to more sustainable levels can help mitigate these dynamics.

Public debt sustainability

Debt sustainability depends upon four key ingredients: primary balances, real growth, real interest rates, and debt levels. Higher primary balances—the excess of government revenues over expenditures excluding interest payments—and growth help to achieve debt sustainability, whereas higher interest rates and debt levels make it more challenging.

For a long time, debt dynamics remained very benign. That’s because real interest rates were significantly below growth rates. This reduced the pressure for fiscal consolidation and allowed public deficits and public debt to drift upwards. Then, during the pandemic, debt increased even more as governments rolled out large emergency support packages.

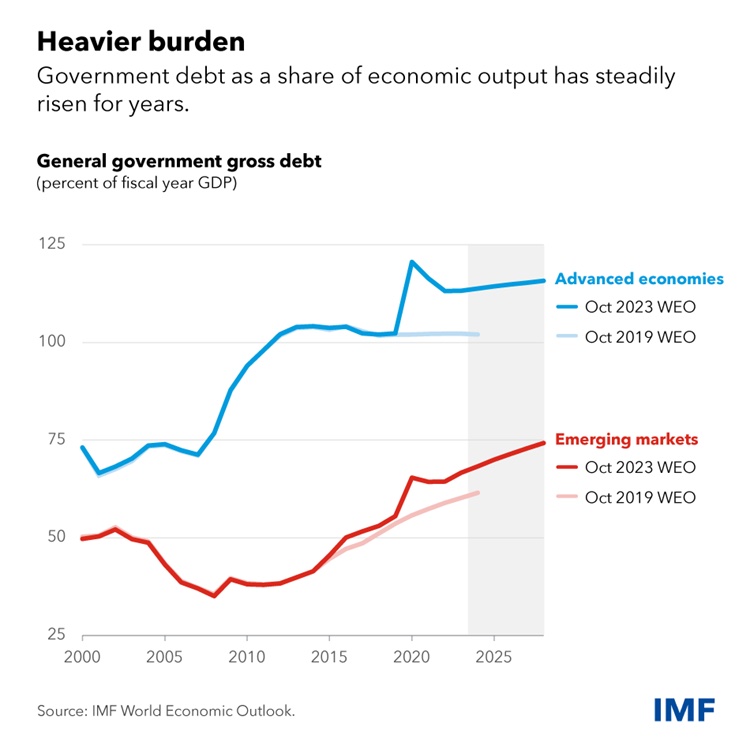

As a result, public debt as a fraction of gross domestic product has increased significantly in recent decades, across advanced as well as emerging and middle-income economies. It is expected to reach 120 percent and 80 percent of output respectively by 2028.

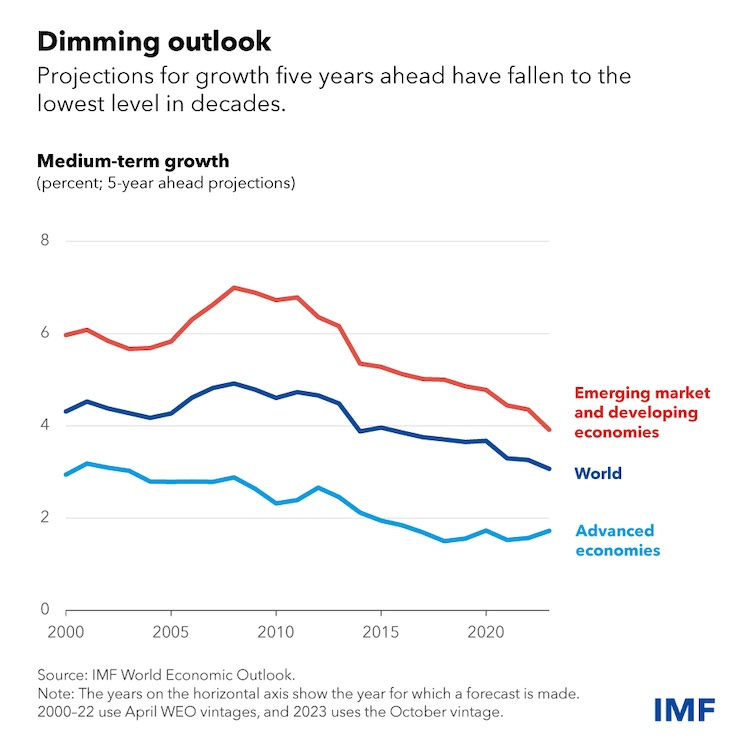

At the same time as we confront higher debt levels, the macroeconomic environment has become less favorable. Medium-term growth rates are projected to continue declining on the back of mediocre productivity growth, weaker demographics, feeble investment and continued scarring from the pandemic.

Against this backdrop, elevated real long-term interest rates could pose significant challenges.

Short- and long-term rates

Public debate has focused on the short-term real interest rate, known as r*, defined as the equilibrium interest rate at which an economy is operating at its full potential while keeping inflation stable. This equilibrium real interest rate has declined dramatically in recent decades driven by slow-moving, structural variables such as demographics, demand for safe assets, productivity growth, or the income distribution. As long as these factors continue on similar trajectories as before the pandemic, equilibrium rates around the world will remain very low as shown in an analytical chapter of the April 2023 World Economic Outlook.

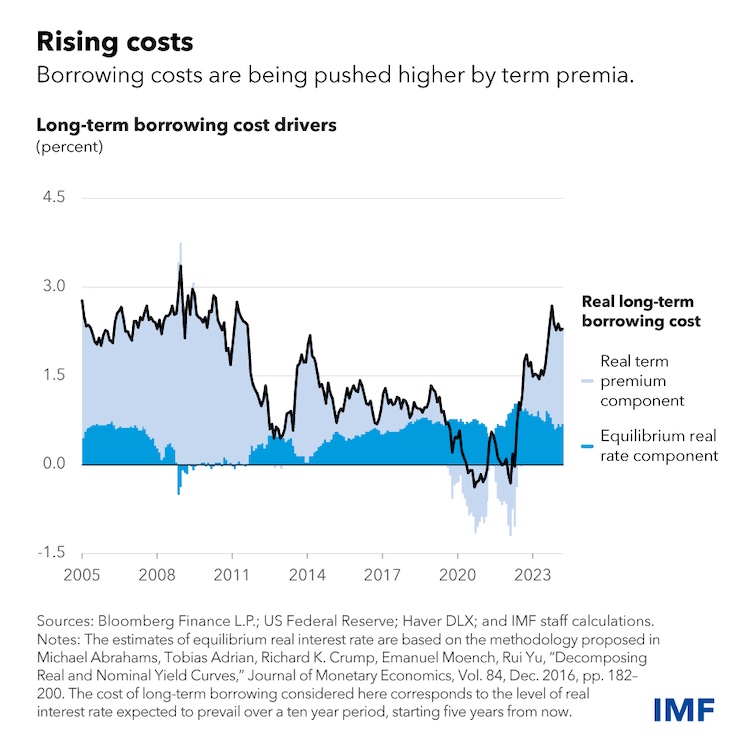

However, even if r* remains low, the real borrowing cost of government, household, and corporate sectors could be higher in the future. This is because they tend to borrow not for short periods, but longer term, and the associated long-term interest rates incorporate a risk premium—known as the term premium—that compensates lenders for providing funds for an extended period of time.

The dynamics of r* and long-term rates can be illustrated in the case of US Treasury bonds, which serve as global benchmark for fixed income markets. The dark blue bars show an estimate for the r* in the United States. This has risen slightly recently but remains at relatively low levels. By contrast, estimates of the term premium, the light blue bars, have risen more markedly over the past year. In fact, the United States Congressional Budget Office has recently warned of the rising debt burden, noting that it could put pressures on the cost of financing.

Longer-term real interest rates are therefore now comparable to their pre-global financial crisis levels in large part due to higher term premium, and there are reasons to believe that may persist:

First, the inflation fight continues. Even as central banks contemplate easing their policy stance, real rates will remain volatile for some time.

Second, the balance sheet normalization that major central banks have started, commonly referred to as quantitative tightening, may also contribute to higher real term premia by increasing the supply of longer dated securities that need to be absorbed by the market.

Third, the rise in interest rates also likely reflects expansionary fiscal policy and longer-term fiscal concerns, at least in some countries. Loose fiscal policy can contribute to higher interest rates, especially when inflation is high, by forcing central banks to tighten even more to achieve their objectives. Loose fiscal policy, if sustained, can also create investor doubts around long-term debt sustainability, leading to higher term premia.

The key point is that despite low equilibrium rates, borrowers in the United States and the rest of the world may face a new normal with significantly higher funding costs than in the past decade.

Financial stability

If improvements in governments’ primary balance cannot be achieved to offset higher real rates and lower potential growth, sovereign debt will continue to grow. This will test the financial sector’s health. First, the so-called “bank-sovereign nexus” could worsen. At high debt levels, governments have less capacity to provide support for ailing banks, and if they do, sovereign borrowing costs may rise further. At the same time, the more banks hold of their countries’ sovereign debt, the more exposed their balance sheet is to the sovereign’s fiscal fragility. Higher interest rates, higher levels of sovereign debt, and a higher share of that debt on the banking sector’s balance sheet make the financial sector more vulnerable.

The bank-sovereign nexus is spreading beyond advanced economies to developing economies and a few vulnerable emerging markets. For example, the median banking system in low-income countries now holds about 13 percent of the country’s sovereign debt, double the share 10 years prior.

What’s more, in a context of limited fiscal space because of high debt, pressures on monetary authorities to tolerate departures from price stability to support public finances or the financial system may rise. This may be especially relevant in countries with high public debt If this were to happen to systemically important countries, financial market volatility could also rise, increasing the cost of financing for businesses and households globally. Debt concerns that spill over to benchmark interest rates could in turn distort asset prices and impair market functioning.

Finally, financial stability could become strained in emerging markets with relatively weaker economic fundamentals, as high debt burdens make them much more vulnerable to capital outflow pressures, exchange rate depreciation, and increased expectations of future inflation.

Policy implications

Some key policy implications follow from the above considerations.

First and foremost, countries should start to gradually and credibly rebuild fiscal buffers and ensure the long-term sustainability of their sovereign debt.

It is easier to rebuild fiscal buffers while financial conditions remain relatively accommodative and labor markets robust. It is harder to do so when forced by unfavorable market conditions. Durable fiscal consolidation will also allow policy rates to fall faster, which should reduce any adverse effects on the macroeconomy. While a substantial fiscal consolidation is necessary, this is not a call for austerity. Too sharp a tack towards fiscal consolidation could backfire by pushing economies into recession. What is needed is for a credible first installment, followed by subsequent, gradual steps in the same direction.

Second, to preserve financial stability, stress tests should adequately account for the impacts on banks and non-banks of higher sovereign interest rates and potential bouts of market illiquidity. Upgrading market infrastructures to improve trading, price discovery, and market depth is also a key policy priority, even in the most liquid sovereign debt markets.

Third, structural reforms should not be postponed. By enhancing future growth, they are the best way to help stabilize debt dynamics.

About the authors:

- Tobias Adrian is the Financial Counsellor and Director of the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department. He leads the IMF’s work on financial sector surveillance and capacity building, monetary and macroprudential policies, financial regulation, debt management, and capital markets.

- Vitor Gaspar has been Director of the Fiscal Affairs Department at the IMF since 2014. He was Portuguese Minister of State and Finance from 2011–13, and has held various positions in European and Portuguese institutions, including head of BEPA at the European Commission, Director-general of Research at the European Central Bank, Director of Economic Studies and Statistics at the Central Bank of Portugal, and Director of Economic Studies at the Portuguese Ministry of Finance.

- Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas is the Economic Counsellor and the Director of Research of the IMF. He is on leave from the University of California at Berkeley where he is the S.K. and Angela Chan Professor of Global Management in the Department of Economics and at the Haas School of Business.

Source: This article was published by IMF Blog