Mars Valleys Traced Back To Precipitation

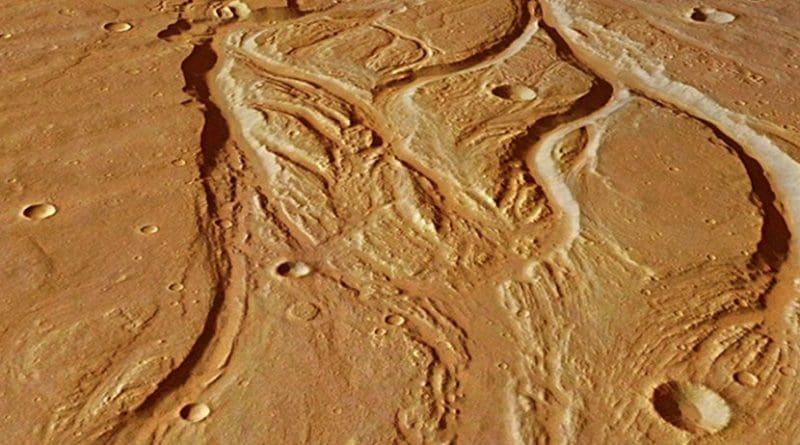

The surface of Mars bears imprints of structures that resemble fluvial steam networks on Earth. Scientists therefore assume that there must have been once enough water on the red planet to feed water streams that incised their path into the soil. For years, however, scientists have been debating the source from which this water must have originated: was it rainwater that caused streams and rivers to swell? Or did water ice in the soil melt due to volcanic activity, and seep out to form rivers? Each of these scenarios leads to a completely different conclusion about the climatic history of the red planet.

A new study now suggests that the branching structure of the former river networks on Mars has striking similarities with terrestrial arid landscapes. This has been demonstrated in a recent paper published in Science Advances by physicist Hansjörg Seybold from the group of James Kirchner, ETH professor at the Institute for Terrestrial Ecosystems, and planetary specialist Edwin Kite from the University of Chicago.

Valleys eroded mainly by rainwater

Using statistics from all mapped river valleys on Mars, the researchers conclude that the contours still visible today must have been created by superficial run-off of (rain)water. Consequently, the influence of groundwater seepage from the soil can be excluded as a dominant process for shaping these features.

The distribution of the branching angles of the valleys on Mars is very similar to those found in arid landscapes on Earth. According to lead author Seybold, this implies that there must have been a similar hydrological environment with sporadic heavy rainfall events on Mars over a prolonged period of time and that this rainwater may have run off quickly over the surface shaping the valley networks. This is how river valleys develop in arid regions on Earth. For example, in Arizona, researchers observed the same valley network patterns in a landscape where astronauts are training for future Mars missions. Valleys in arid regions fork at a narrow angle.

The branching angles on Mars are comparatively low. Seybold therefore rules out the influence of groundwater sapping as the major channel forming process on Mars. River networks that are formed by re-emerging groundwater, as found, for example, in Florida, tend to have much wider branching angles between the two tributaries and do not match the narrow angles of streams in arid areas.

Conditions such as those found in terrestrial arid landscapes today probably prevailed on Mars for only a relatively short period about 3.6 to 3.8 billion years ago. In that period, the atmosphere on Mars may have been much denser than it is today.

“Recent research shows that there must have been much more water on Mars than previously assumed,” said Seybold.

Evaporation made it rain

One hypothesis suggests that the northern third of Mars was covered by an ocean at that time. Water evaporated, condensed around the high volcanoes of the highlands to the south of the ocean and led to heavy precipitation. As a result, rivers formed, which left traces that can still be observed on Mars today.

The big question is where the water has disappeared to over time.

“It’s likely that most of it evaporated into space. But it could still be found in the vicinity of Mars,” said the physicist, ” but this is a question for a future space mission”.