China And Latin America: ‘Love’ Based On Money And Ideology – Analysis

By Matija Šerić

China’s ties with Latin America date back to the 16th century, when sea trade routes enabled the exchange of porcelain, spices and silk between China and Mexico. By the 1840s, hundreds of thousands of Chinese immigrants had gone to work across the Pacific Ocean as traditional laborers or servants, mostly in Cuba and Peru, often on sugar plantations or silver mines. During the 20th century, China-Latin America ties were mostly linked to migration as Beijing remained preoccupied with domestic problems such as World War II, the Chinese Civil War, and the development of a socialist order.

Slow relationship development

From 1949 to the beginning of the 1970s, most Latin American countries recognized the Taiwanese government of the Republic of China as legal and legitimate, which of course made it impossible to build relations with the People’s Republic of China on the Chinese mainland.

However, after US President Richard Nixon’s trip to Beijing in 1972, most countries in the region recognized the Communist PR China as China’s legitimate representative on the international stage. The growth of the relationship was very slow and sluggish. China has been more strongly interested in Latin America only since the later stages of the Cold War. In general, until the late 1990s, relations between Latin America and Asia were limited, with the exception of Japan, which established strong political and economic ties with several countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and Peru.

A big turn at the beginning of the 21st century.

In 2000, only 2% of Latin American exports went to China. But then a major turnaround took place, due to four factors: 1) China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 made trade easier; 2) the rapid development of the Chinese economy has drastically increased China’s demand for resources; 3) there was an increase in the export of natural goods from Latin America; 4) the mass coming to power of left-wing governments in Latin American countries (“pink tide”). Only then, in the first years of the 21st century, the two sides began to create tangible economic, political, cultural and other ties.

In the last two decades, China has cordial relations with Latin American countries to such an extent and with such potential that it could be said that Latin America is becoming more and more China’s backyard and less and less American. China’s political engagement since the early 2000s has been based on a strategy of “South-South” or “mutually beneficial” cooperation.

The Chinese foreign policy principles of “respect for sovereignty” and “non-interference” (in the internal affairs of other countries) merged with the political-economic interests of the leaders of the Latin American left (Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Lula da Silva in Brazil, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador ). Although Latin American left-wing leaders were wary of the possible disruption of privileged trade relations with the US, they were attracted by the idea of stronger economic cooperation with Beijing, which could reduce their dependence on America. And that dependence is really reduced.

China – the region’s key trade partner

In the last two decades, China has become a key trading partner of Latin America. Compared to the US and the EU, trade with China has grown dramatically: from $14.6 billion in 2001 to $450 billion in 2022. During the same period, trade between the US and Latin America nearly doubled from 364 billion dollars to 758 billion dollars, while trade with the European Union doubled from 98 billion dollars to 197 billion dollars. This increase allowed Beijing to become the most important exporter of goods to South America and the second largest trading partner of Latin America as a whole, behind the US but far ahead of the EU. Economists and analysts estimate that the trade exchange between China and Lat. America could exceed 700 billion dollars by 2035.

Latin American exports to China mainly refer to the export of natural goods such as oil and oil products, iron ore, coal, aluminum, copper, wood, soybeans, sugar, meat and other raw materials that the second most populous country in the world needs to maintain industrial development and feed a huge population. of the population whose standard is raised year after year. In turn, China mainly exports high-value manufactured products intended for national economies and ordinary citizens. China is relentlessly increasing its financial involvement in the region.

Chinese loans

Since 2005, China’s two main state-owned banks (the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China) have provided $141 billion in loans to Latin American governments and their companies. This amount exceeds the loans of the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank and the Latin American Development Bank. Loans refer mostly to four countries (Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela), which account for almost 93% of all loans. The largest part of these loans was spent on energy (69%) and infrastructure (19%) development projects. In total, Latin America received 24% of loans granted by China’s state-owned banks worldwide between 2005 and 2021, ranking behind Asia (29%) but ahead of Africa (23%). China is a voting member of the Inter-American Development Bank and the Caribbean Development Bank.

Why are Chinese loans so desirable to Latin Americans? Chinese banks have become attractive as lenders as governments have lost the confidence of traditional international lenders, the IMF and the World Bank. The specificity of Chinese credit agreements is that they contain special confidentiality clauses and ensure repayment priority over other creditors.

According to a recent study of 100 loan agreements, many loans have built-in security mechanisms, such as Chinese-controlled foreign currency bank accounts. According to this model, the profit from the sale of goods by the debtor is deposited in a foreign currency account controlled by Beijing. The Chinese control serves as collateral for the loan. As a result, the loans represent a significant political advantage for Beijing. Even in the absence of asset seizures to offset debt, continued debt pressure shapes the national policies of states towards Beijing in the long run. In Ecuador and Venezuela, China’s advantage is reflected in the purchase of oil at discounted prices.

Although China’s loans are covered by the delivery of Latin American resources such as oil or minerals, the drop in world oil prices has forced both countries to supply more oil to China. Some analysts have negatively characterized “Chinese loans” as “debt trap diplomacy” that could result in the inability to meet credit obligations.

China’s foreign direct investment

In Latin America, Chinese companies embarked on foreign direct investment: they invested about $160 billion in about 480 transactions between 2000 and 2020, mostly through mergers or acquisitions of existing companies, and to a lesser extent the creation of new companies. Direct foreign investments go mostly to the construction of refineries and factories for the processing of coal, copper, natural gas, oil and uranium.

Recently, Beijing has invested approximately 4.5 billion dollars in lithium production in Mexico and the countries of the so-called. Lithian triangle: Argentina, Bolivia and Chile. Those three countries own more than half of the world’s lithium, the metal needed to produce electric vehicle batteries. China is also interested in the renewable energy sector. China Development Bank has financed large-scale solar and wind farms, such as the largest solar farm in Latin America in Jujuy, Argentina, and the Punta Sierra wind farm in Coquimbo, Chile.

Beijing has also financed construction projects across the region, focusing on dams, ports and railways. China is also focused on “new infrastructure”, such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, smart cities and 5G technology. Beijing also seeks to strengthen space cooperation with Latin America, beginning with joint Sino-Brazilian research and production of satellites in 1988.

China’s largest overseas space facility is located in the Patagonian desert in Argentina, and China has satellite stations in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela. However, the importance of China in the field of foreign direct investment in the region should not be overestimated. The USA and the EU are responsible for about 70 percent of foreign direct investment in the region between 2010 and 2020.

Military and medical cooperation

China is also strengthening ties with the region through military cooperation that includes arms sales, officer exchanges and training programs. Venezuela became the largest buyer of Chinese military equipment in the region after the US government banned all arms sales to the country starting in 2006.

Between 2009 and 2019, Beijing sold more than $615 million worth of weapons to Venezuela. Bolivia and Ecuador have also bought millions of dollars worth of Chinese military aircraft, ground vehicles, air defense radars and assault rifles. The Cuban government hosted the Chinese People’s Liberation Army several times. China participated in the UN peacekeeping mission in Haiti. The Chinese have supplied Bolivian police with riot control equipment and military vehicles, and donated transport equipment and motorcycles to police forces in Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago.

During the corona crisis, China delivered more than 300 million doses of vaccines to Latin America, more than three times what was provided to the region by the global COVAX initiative. Numerous medical equipment such as masks, respirators, hospital beds were also delivered.

Bilateral and multilateral approach

China’s economic penetration has been supported and accompanied by greater foreign policy engagement in Latin America at both the bilateral and multilateral levels. After all, economy and trade are part of national politics.

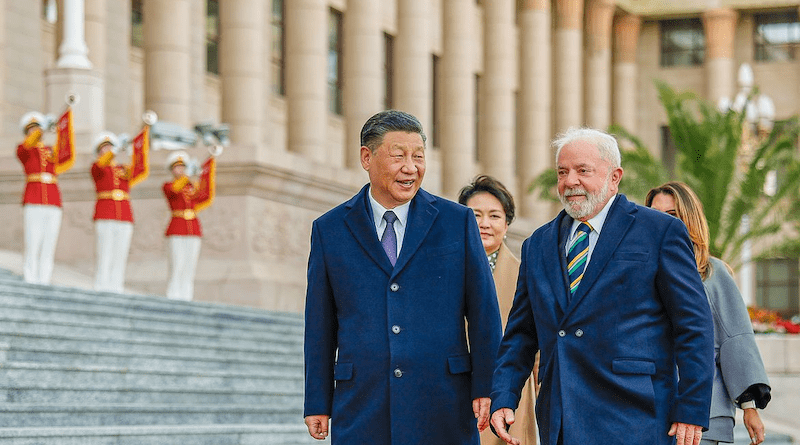

Since former Chinese President Jiang Zemin’s 13-day tour of Latin America in 2001, there have been many high-level visits by statesmen and diplomats. President Xi Jinping has visited the region eleven times since taking office in 2013.

Bilaterally, Beijing relies on strengthening political dialogue with each country to promote its interests in the region through the use of classic 1-on-1 diplomacy. Beijing has free trade agreements with Chile , Costa Rica, Peru and Ecuador, and similar agreements exist with other countries, only with a different name.

For example, in April of this year, during the visit of Brazilian President Lula da Silva to China, the two countries signed more than 20 agreements, including an agreement on mutual trade in yuan and reals, which is a direct slap in the face of America and a way to speed up the de-dollarization of the world. China has signed comprehensive strategic partnerships (China’s highest level of cooperation) with Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela.

On the multilateral front, China pursues a long-term strategy of participating in regional projects or organizations. China’s interest in the region is most clearly seen in the context of China’s New Silk Road, which was expanded to Latin America in 2017.

Since then, around 20 countries in the region have signed a memorandum of cooperation with China in the New Silk Road project. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Uruguay are members of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The Chinese diaspora in South America is numerous and there are many Chinese in countries such as Peru, Brazil, Cuba, Paraguay and Venezuela. Diaspora of course has influence in all these countries and it often serves as a bridge to connect two countries.

Chinese soft power

The Chinese, of course, also play the soft power card, and through the strengthening of cultural and educational ties, they are establishing themselves as a desirable alternative to other rivals. Soft power in practice implies the establishment of Confucius Institutes, “diplomacy between nations”, media presence, high-level public diplomacy and the activities of Chinese companies.

Soft power is taking place in line with Xi Jinping’s 2022 guidelines to “strengthen and improve international communication work”. China has established 44 Confucius Institutes as well as 18 affiliated Confucius Classrooms to teach Chinese language and culture. Although the Confucius Institutes are not spy bases as Americans often portray them, their students go to China to study and if they are willing can work for the Chinese security and secret services since few people abroad in general, and especially in the Western Hemisphere, speak Mandarin.

Motives of cooperation

The motives for cooperation between Chinese and Latin Americans are diverse, but they can be reduced to two main motives: money and ideology. In terms of money, everything is clear. Merchandise trade takes place because Latin American countries are abundant in natural resources such as oil, coal, iron ore, lithium, healthy food, and China needs these resources to continue to record GDP growth and feed its population.

Also, Latin America is an ideal area where China can sell its consumer goods as well as “high-tech” technology, including military and space technology. Many countries such as Venezuela or Cuba know how to record shortages of food and various other necessities, and China is the one that can literally flood every country with “Made in China” products. Beyond profit in any form, Sino-Latin American relations are driven by ideology. One could more precisely say two ideologies: the ideology of socialism and the ideology of anti-Americanism.

Socialist agenda

Both sides are linked by belonging to the left political spectrum and the socialist character of the ruling parties and regimes. Both Chinese and Latin Americans, at least nominally, swear by some kind of socialism of the 21st century, although in essence it is mostly state-controlled capitalism or a hybrid economic system.

Even if we accept that China is not economically a socialist country, socialism is not only an economic category but also a political and social agenda. This agenda is most often manifested through the authoritarian character of governments, state control of society, repression of the opposition, etc.

It is not surprising that authoritarian left-wing governments in Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela fanatically support cooperation with China. But this cooperation is also supported by the moderate left-wing governments of the region, such as the Mexican government of López Obrador, the Brazilian government of Lula da Silva or the Bolivian government of Luis Arce.

Anti-Americanism

Why? Because an integral part of the socialist agenda is anti-Americanism. The countries of Latin America are looking to China for salvation from American hegemony based on the Monroe Doctrine, which implies that there can only be one boss in the Americas, the US, and all others are vassals. Somewhat ironically, thanks to Beijing, the voice of the small states of the region can be heard in the international arena and American attempts to change the regime through internal coups and international sanctions can be neutralized.

All Latin American countries are small in real terms, except for Brazil, Argentina and Mexico, but their vote is worth more if they are supported by China. And China, like Russia, propagates a multipolar world order that would be fairer because power in the world would not be based on the results of the Second World War. One Brazil should definitely have more geopolitical power and be a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Why not Mexico, which is the most populous Spanish-speaking country in the world (126 million inhabitants) and has often been and remains the target of its northern neighbor. China is also presented as a desirable trade alternative to the USA because the countries of Latin America can levitate between the two superpowers and import and export where it is more convenient for them.

Even though China is a powerful force, it benefits geopolitically from cooperation with the states of the region. China’s desire to isolate Taiwan is an important motive for Chinese engagement. Since Beijing in principle refuses to have diplomatic relations with countries that recognize Taiwan’s sovereignty, Latin American support for the island has decreased in recent years. Only eight other countries recognize it. The Dominican Republic and Nicaragua recently reversed their positions after China offered them financial incentives, including loans and infrastructure investments.

Recently, Beijing has been making the issue of Taiwan a reality, and any diplomatic help is welcome here. In addition, the chances that the world order will be formally reformed in a multipolar direction are greater if it is supported by as many countries as possible in the UN, WTO and other organizations. Additionally, partnering with any country is attractive to the Chinese as it curbs American global power and brings them closer to what is being called the Chinese Century.