Significance Of 20th Congress: Is Xi Jinping Leading China To Prosperity Or To Communist Games Of Thrones? – OpEd

By Matija Šerić

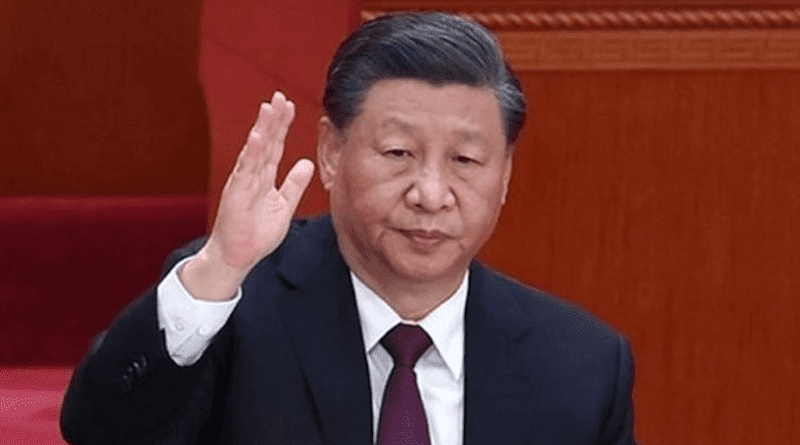

At the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of the People’s Republic of China (CPC) in October, Xi Jinping won his third term. Xi confirmed his position as an untouchable authoritarian leader by being re-elected to the post of General Secretary of the CCP (and at the same time President of China), while simultaneously strengthening his position at the expanse of party’s collective chairmanship mechanism. More specifically, Xi has consolidated an enormous amount of power that makes him arguably the world’s most powerful individual politician. By all accounts, after decade of power, China will still be ruled by Xi and his associates for many more years. In the international arena, it is expected news that some are looking forward to and some are worried.

Although the decision-making process in the personnel affairs of the Chinese Communist Party has always been non-transparent, this time the non-transparency has increased. Xi has filled the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee with his allies, showing that informal rules on membership in the body such as age and experience can be applied selectively from now on. In fact, almost all members of the Standing Committee (the highest body of the Communist Party) are now people believed to belong to Xi’s faction. There are currently seven of them. Along with Xi, Li Qiang, Zhao Leji, Wang Huning, Cai Qi, Ding Xuexiang and Li Xi are sitting there. It is striking that there is not a single woman. The formal purpose of the Politburo Standing Committee is to conduct policy discussions and make decisions on major issues when the Politburo, the larger decision-making body, is not in session.

The number of Politburo members currently stands at 24, up from the usual 25. Xi has destroyed any semblance of factional balance, symbolized by Hu Jintao’s dramatic exit from the congress. To celebrate their victory, Xi’s new team visited the site of the 7th CCP National Congress in Yan’an, citing the supremacy achieved by Mao Zedong in 1945.

There have been important personnel changes in economic and fiscal policy. Li Keqiang, Wang Yang, Hu Chunhua and other reformists were sidelined. It is evident that other reformers will also be suppressed. On the other hand, loyalists such as Wang Huning and Zhao Leji have shown their ability to strengthen Xi’s key role and have therefore been promoted. With the expected 2023 appointments of Li Qiang as premier and Ding Xuexiang and He Lifeng as vice premiers, Xi is bringing his inner circle of associates to the top of the state apparatus. This will further blur the already weakened dividing lines between the party and the state.

Similarly, the security apparatus is now dominated by officials close to the chief secretary. They include Li Xi (anti-corruption czar), Chen Yixin (minister of state security) and Ying Yong (presumptive chief prosecutor), as well as the previously appointed Wang Xiaohong (minister of public security) and Tang Yijun (minister of justice). The military top is also dominated by Xi’s allies. The detention of 72-year-old General Zhang Youxi is a strong indication of the president’s tight control over the armed forces.

A number of previous rules were broken at the congress. Most important of all, the democratization within the party that had been going on since the eras of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao was interrupted. As a result, generational change was delayed, and China’s “seventh generation” of fifty-year-olds, mostly born in the 1970s, missed out on becoming members of the Politburo. Perhaps Xi is distrustful of the younger generations who did not experience the Cultural Revolution. It is interesting that his successor was not named. The Central Military Commission has no “civilians” except for Xi himself. This made it more likely that Xi Jinping would remain the party’s general secretary for the next 10 years until 2032. All of these moves made the 20th Party Congress an event that destroyed the “collective leadership” that had been established after the death of Mao Zedong in the late 1970s. Instead of adhering to the criteria of ability when hiring and introducing so many democratic reforms of the regime, Xi revitalized the system of unilateral rule by the supreme leader.

Apart from personnel moves, the main result of this congress was the inclusion of two “institutions” and two “protective measures” in the KPK constitution. According to the historic resolution of the CPC in 2021, the two institutions read: 1) “establish the status of Comrade Xi Jinping as the leader of the party’s Central Committee and the entire party”, 2) “establish the leading role of Xi Jinping’s thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics in the New Era”. According to 6th plenum of the 19th Central Committee, the two safeguards are: 1) “to protect Xi Jinping’s leadership status in the CCP,” 2) “to protect the party’s centralized power.” According to leading party theorists, having a “centralized and unified leadership” is necessary to achieve national rejuvenation and dealing with “changes unseen in a century.” At first glance, this seems like a decorative speech by the communist apparatus to give symbolic support to the Secretary General. However, it is not only a symbolic gesture but also a re-establishment of the framework in which one man has the enormous concentration of power in the party and the state. It is the culmination of a multi-year effort to legitimize Xi Jinping’s authoritarian rule in China. After gaining the status of undisputed leader in 2016, Xi continued to present his “New Era” philosophy at the 19th Party Congress in 2017. The two pillars of protection first appeared in the party’s 2018 disciplinary regulations and are further documented in the “Historic Resolution” in 2021.

Although the 20th Congress will be remembered for the violation of previous standards, it confirmed some long-standing practices. For example Li Qiang’s promotion to the Politburo Standing Committee means that all Shanghai party secretaries since Xi himself in 2007 (and all but one since 1987) have joined the Communist Party’s top body. This is precisely why the new city leader, Chen Jining, is a potential party hope at the 21st Congress in 2027.

By filling the highest party bodies with his allies, Xi has shown that party institutions and the people who hold them are still important as a source and display of power. Although immensely powerful, Xi remains a party man. Paradoxically, although he has broken many of the party’s institutional norms, he cannot do much if he remains without the support of his party comrades and friends.

Xi’s speech to the congress as well as the appointments of selected officials placed a strong emphasis on national security to further strengthen the government’s control over Chinese society, while assuring members of the Communist Party and the Chinese people, including minority ethnic groups and Taiwanese, that they share the same “Chinese Dream.” Although Xi emphasized the importance of unity, it does not rest on pluralism but on plebiscite support for him as the undisputed leader. Along with national security, it was precisely national unity that was emphasized in the speeches and decisions at the congress. It is noticeable that communist officials are not sure whether China can achieve its proclaimed goals and become a “modern socialist country” by 2035, and a “great modern socialist country” by 2049. The cause is the slowdown in economic growth, including the Covid crisis as well as the trade war with the USA. For all these reasons, Xi seeks to strengthen his vision of the unity of the Communist Party and the Chinese people. It is obvious that insecurity is felt even in the highest Chinese leadership.

Also, it is striking how the focus of the Politburo has been redirected from monetary and fiscal issues, i.e. the emphasis is on “common prosperity for all”. Given that reforms and economic opening are what drive cooperation with the West, this orientation towards the “common” will affect China’s foreign policy position. In other words, more serious confrontations with the West are possible because the Chinese leadership says that they are open to trade and profit, but they will not allow the violation and even less the sacrifice of national sovereignty in any form. A good example is the attitude towards Taiwan.

Although some statements about Taiwan were included in the party constitution, there was no significant change in expression. The basic position of the Chinese Communists is to “win without a fight” by 2049 and integrate Taiwan with the rest of the country. Beijing considers the people of Taiwan to be an integral part of the Chinese nation and assumes that they will share the same “dream”, which is why the official goal is to incorporate Taiwanese into Chinese society. In other words, he will continue the policy of unification by increasing military pressure, penetrating Taiwanese society with soft power, applying economic and other measures. The question is what will happen if Xi starts to see this policy as ineffective, because then he might resort to more clanging weapons.

During his decade in power, Xi has shaped China’s foreign policy by creating a rivalry with the US. In doing so, he put the US on the defensive like no previous Chinese leader. Due to its successful competition with America in terms of economic and political influence (mostly due to the Belt and Road Initiative), it received loud applause in some parts of the world such as Moscow and Tehran, and harsh condemnation in other power centers such as London and Bruxelles. Although Western diplomats have been vocal in criticizing the Chinese leadership over its policies toward Hong Kong and Taiwan, they are far more concerned about China’s industrial policies that favor large Chinese state-owned companies over multinational corporations.

Under Xi, Beijing has adopted laws designed to punish companies deemed anti-Chinese. He kicked out of the country certain American journalists who wrote derogatory articles about China and showed the world the growth of Chinese technology, including the rise of the TikTok app. Xi’s determination to put China’s stamp on important decisions at the UN and similar organizations worries Washington. Essentially, Xi wants to become China’s most successful contemporary leader and enable a national revival for his nation of 1.4 billion people. At the same time, he managed to drastically increase China’s global influence, but also to increase the headaches of American policymakers in an unprecedented way. The strategic partnership with Putin’s Russia is a special story that most directly opposes the still active American pursuit of a unipolar order. At the time of writing, in his 10-year reign, Xi has made 42 international trips, visiting as many as 69 countries. No American president has ever done that in his entire life.

The centralization of power in the hands of one man brings great risks, but also potential benefits for the Communist Party and the Chinese state. On the one hand, the party could act with more unity and determination on key political issues. On the other hand, Xi’s revival of autocracy inadvertently undermines the long-term resilience of the socialist system. Without strong executive control mechanisms and weaker information flow, misjudgments by China’s top leadership seem more likely than before. Xi’s purging of potential and actual party rivals leaves little room for shifting blame when and if the country gets into serious trouble, and also dramatically increases the prospect of a fierce power struggle when sooner or later Xi leaves power. Communist games of thrones could happen. It is well known that one-party communist systems are very vulnerable when they are not unified, which was clearly seen in the examples of the USSR and Yugoslavia during the 1980s. Back then, internal disputes were the catalyst for the collapse of these bastions of socialism. Admittedly, although this option is unlikely, if China falls into a serious economic crisis and recession and if widespread social unrest occurs, it is not excluded that Xi in office may experience a coup attempt.

But if we return to the present moment, the current question is how will Xi continue to deal with certain dissatisfaction within the party due to his personnel policy, the slowdown in the growth of the Chinese economy and social dissatisfaction with countermeasures to combat the Covid-19 pandemic? Xi’s administration is likely to act preemptively against social discontent by touting major achievements, the democratic spirit of the 20th Congress and the creation of better-paying jobs, while at the same time using “national security” as an excuse to crack down on potential rebels through digital surveillance and other repressive measures. Yet in reality, the Chinese establishment can sleep peacefully as long as it continues to deliver on its promises of economic prosperity and other material benefits. The question everyone is asking is whether Xi and his comrades will continue to ensure rising living standards and a better life for the average Chinese in the future?