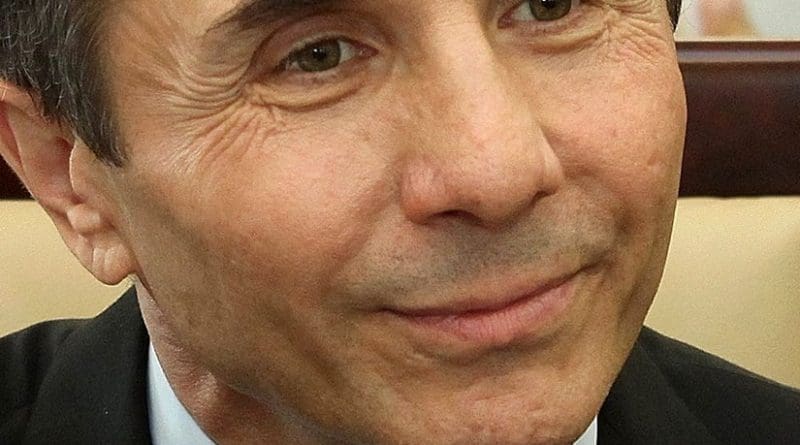

Georgia: Billionaire Ivanishvili’s Big Talk

By Eurasianet

By Giorgi Lomsadze*

Love him or hate him, Georgia’s richest man Bidzina Ivanishvili is the main show in town. When he gives one of his lengthy, oracular media appearances, everyone seems glued to their TV screens to get a read on where he is taking the country.

In his latest interview, a 45-minute sitdown with Georgia’s Channel One, the billionaire ex-prime minister essentially asked the voters to stick with him and the government of his choosing until at least 2030, when he expects Georgia to have finally reached the promised land. Georgia will be home free then, Ivanishvili said, with the country’s gross domestic product per capita having almost tripled to $10,000 or – fingers crossed – even $12,000, and the Georgian dream of joining the European Union already a reality.

Ivanishvili, who is widely seen as a behind-the-scenes puppetmaster of Georgian politics, was disarmingly honest in the interview about the influence that he has maintained over the government and the ruling Georgia Dream party since stepping down as prime minister in 2013. He expounded on how he has participated in key government decisions, such as selecting the new prime minister and searching for a candidate for new president, but denied that all that amounted to being the shadow ruler of Georgia.

“They are confusing informal governance with public oversight,” Ivanishvili told Channel 1. “The public put a degree of trust in me and I can use this trust at any moment and criticize any leader. […]We don’t have an extensive experience of public oversight of the government and I’m there to fill that gap.”

Ivanishvili played that role for five years before returning this year to formal politics, taking over the chairmanship of Georgian Dream.

Part of the reason he came back was the sinking morale in the party that he had founded and led to power in 2012. “There was a serious risk of the team falling apart,” he said. “I was watching this from the outside and, at a critical point, I realized that exercising remote control was not enough […] to keep the team together.”

Ivanishvili admitted that he participated in selecting former Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili’s replacement, Mamuka Bakhtadze, and advised the new, young head of government on cabinet appointments.

But Ivanishvili is no control freak. “I don’t want the society and also you, the journalists, to believe that I’m doing everything and I make all the decisions,” Ivanishvili told his interlocutor, Maka Tsintsadze. Ivanishvili is not like a certain former leader, his unmentionable nemesis, former President Mikheil Saakashvili, who, as Ivanishvili put it, ran the whole show, selected the cast, the setting and the musical score. “God spare us from governance like that!”

On the ongoing search for the Georgian Dream’s candidate for the presidential election this fall, Ivanishvili said that he prefers to have a non-partisan candidate or even let the opposition take the presidency, which has been reduced to a ceremonial role. “It will be good for democracy,” he said.

Georgian democracy, he said, is developing so fast that the economy can’t keep up with it. And it is a recipe for trouble when people are poor but have all the democratic avenues to complain about it, Ivanishvili said. The stability of the nation is under threat when “the fridge is empty,” as he put it, and the GDP per capita is a meager $4,000, yet “freedom of expression is fully realized” and “there is plenty a political opportunist out there.”

And he was not fully aware how bad the economy was faring because the government officials hid it from him, he claimed: “I was crestfallen for several days after I had found out that the economic situation got worse for a certain part of the society following Georgian Dream’s rise to power.”

That was part of the reason Kvirikashvili had to go, Ivanishvili said. Kvirikashvili concealed the true state of economic affairs – citizens’ overdependence on bank loans – “from me and the society.”

His interviewer asked Ivanishvili another key question: what’s with his whim of uprooting and moving giant, century-old trees to his new park, a pastime that left patches of green land near the Black Sea coast defaced and deforested. “Where are you taking these trees?” Tsintsadze asked.

“I know people are saying, ‘what is wrong with this guy?’” Ivanishvili conceded, but added that it is only for the good of the people. He compensated farmers and the Georgian railway authorities lavishly for the interruptions that the movement of giant trees may have caused. The barges and the heavy machinery he brought to Georgia to move the trees will stay in the country, and will potentially serve the public good, Ivanishvili said.

He also defended another of his pet project, a pharaonic real estate complex that is controversially under construction in and around capital Tbilisi’s historic center, with its several segments to be connected with aerial trams. Ivanishili said that having a golf course a mere four-minute cable car ride from downtown will be a huge boon for the economy, and played down the project’s impact on the city’s rich architectural heritage and its environment.

Georgians reacted to the interview with everything from face-palms, to praise to condemnations. “We see a total evasion of responsibility for things that he [Ivanishvili] is responsible for,” said Elene Khoshtaria, a member of opposition party European Georgia, in comments to TV Priveli. “He installs people to lead the government, vouches for their qualifications and then replaces them if the public is disappointed, without taking any responsibility for it,” Khoshtaria said.

Georgian Dream supporters were happy with their chairman’s interview, though some insisted that the party should have a candidate for the upcoming elections. “The society may not understand why the ruling party declines to participate in the presidential elections, said one party member, Tamar Chugoshvili.

*Giorgi Lomsadze is a journalist based in Tbilisi.