Modern Ramsethu: An Unlikely Bridge To Sri Lanka – Analysis

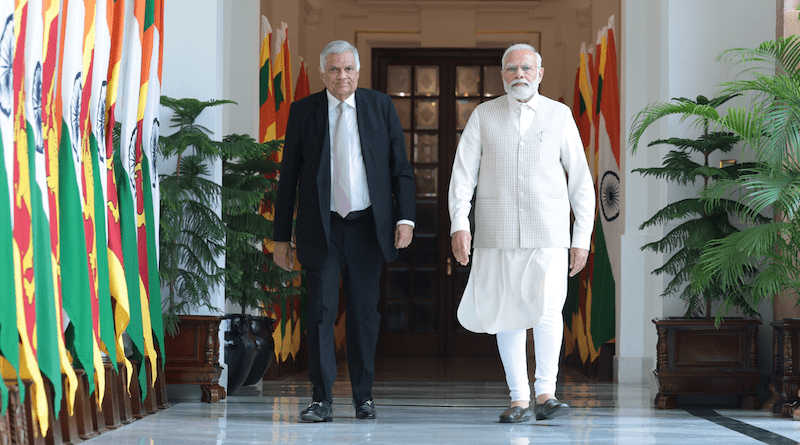

One of the highlights of President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s India visit last month was the agreement “to establish land connectivity between Sri Lanka and India.” Land connectivity between India and Sri Lanka means building a bridge from the Ramanathapuram region to Mannar, a modern Ramsethu. The parties are also discussing a tunnel. The two countries agreed to undertake a “feasibility study” for land connectivity “at an early date.”

This is not the only agreement reached between the two countries during the president’s visit. For example, the leaders agreed to resume flights between Jaffna and Chennai, resume passenger ferry service between Nagapattinam and Kankesanthurai, and establish a high-capacity power grid between the two countries. The decision to develop land connectivity is controversial compared to the other agreements. This article argues that the envisioned modern Ramsethu would not be built for political reasons.

Premature Enthusiasm

President Wickremesinghe’s visit and the agreements reached created a lot of enthusiasm in India about an intensified partnership between the two countries. For example, an official of the Center for Social and Economic Progress declared that the outcome of the visit shows that India “will be the most important partner for Sri Lanka to reset its economy, its bureaucracy, its decision-making system for future economic partnerships” (Aljazeera, July 21, 2023).

A notable factor is that Wickremesingh’s visit to New Delhi and the agreements reached did not generate the same enthusiasm in Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan commentators have approached the possible close partnership idea with either caution or from a critical perspective.

The Indian hope of becoming the most significant partner of Sri Lanka is premature, and it fails to appreciate Sri Lanka’s domestic and regional realities. During the last phase of the war with the LTTE, India offered considerable assistance to Sri Lanka. For example, based on intelligence provided by India, the (Sri Lanka) navy destroyed several LTTE ships, curtailing arms supplies to the Tamil rebels. India joined the “troika,” a three-person committee formed to speed up war-related decisions. In other words, India extensively helped Sri Lanka finish the LTTE, believing that Sri Lanka would cater to its national interest and security needs in a post-LTTE environment. India was disappointed.

The Rajapaksa government sidelined India as it leaned drastically towards China. China became the darling of Sri Lanka. Consequently, India lost the battle with China in Sri Lanka after the end of the war. It was the economic crisis of 2022 that (temporarily) halted China’s buildup in Sri Lanka and allowed India to reenter the competition. India returned by providing about four billion dollars in financial and humanitarian assistance to Sri Lanka during the crisis. Therefore, India is back in the game but has not won the battle as some Indians presume. Therefore, the Indian enthusiasm about forging the most important partnership with Sri Lanka is premature. It could be sidelined again.

One of the reasons why India was almost wholly sidelined was China’s economic capabilities. It is a twenty trillion-dollar economy and the world’s largest by purchasing power parity. Although substantial, the Indian economy is worth only about four trillion dollars. Therefore, India could not compete with China in terms of catering to Sri Lanka’s post-war needs and ambitions. However, the most significant reason India was sidelined was fears of the Sinhala people in general and the Rajapaksa government in particular. These two factors would once again make the envisioned bridge an unlikely project.

The Bridge

Indian media reports suggested that Ranil Wickremesinghe proposed the land bridge project. For example, according to Nikkei Asian Online (July 21, 2023), Indian Foreign Secretary Vinay Kwatra claimed that the land connectivity “idea was proposed by the Sri Lankan president and both leaders agreed to take this forward.” I doubt that Ranil Wickremesinghe proposed the idea because he had never enthusiastically discussed the bridge project. He also knows there is no enthusiasm about the bridge on this side of the Palk Strait.

On the other hand, Indians are very excited about the bridge (or a tunnel), especially the Narendra Modi government, which is keen to build the bridge as a greater South Asian integration project. For example, in a 2015 (December 16) report, The Economic Times stated, “keen on promoting connectivity in the South Asian region, India is set to build a sea bridge and tunnel connecting Sri Lanka.” The report also quoted India’s Road Transport and Highways Minister Nitin Gadkari saying that the land connection “project was also discussed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi with his counterpart during the latter’s recent visit.” The bridge is an Indian idea.

The vision statement issued after Wickremesinghe’s visit claimed that the land connectivity is proposed to “propel economic growth and prosperity in both Sri Lanka and India.” However, the reality is different. India is keen to build the bridge because it would easily bring the small island nation into India’s sphere of influence. India could also send its military and reinforcement to Sri Lanka easily in a crisis. For example, when foreign powers try to station their military in Sri Lanka. One cannot rule out the possibility of full or semi-stationing of Chinese or the U.S. forces in Sri Lanka. Therefore, from an Indian perspective, the proposed bridge is more of a strategic military instrument than an economic propeller.

An Indian Dream?

As I have already pointed out, the bridge cannot be built in the near future. Three significant factors could halt this project. They are (1) the Southern, especially Sinhala fears, (2) Ranil Wickremesinghe’s realities, and (3) China. The Sri Lankan fear of a land connection with India could be divided into three categories: (1) fear of Indian dominance, (2) fear of Eelam, and (3) concerns about the possible economic impact.

Sinhala nationalists, not without reason, believe that a land connection with India would undermine Sri Lanka’s freedom and independence. It is possible that Sri Lanka remained an independent state partly due to its isolation from the Indian Subcontinent. Currently, the parties have only agreed to undertake a feasibility study. No concrete steps have been taken. Sinhala nationalist critics are already out with condemnation. For example, Colombo Archbishop Malcolm Ranjith recently accused the government of selling the country to India by agreeing to the bridge idea. According to a recent news report, the bishop claimed that “by selling parts of our nation, Sri Lanka is bowing to other nations. The authorities are making various stupid decisions leading the country towards destruction. Having gained freedom, we now have to lose freedom” (Newswire, August 28, 2023). The bishop insisted on a national referendum to decide on the proposed bridge. Bishop Ranjith is an intelligent activist. He insists on a referendum because he knows well that the bridge project will not pass the referendum test.

Some Sinhala commentators also believe the bridge could promote separatism in Sri Lanka. Dayan Jayatilleka, calling the proposed land connection a danger to Sri Lanka’s “collective existence,” argued that it should not be built because the “North and East of the island of Sri Lanka will always be predominantly Tamil-speaking” (The Island, August 6, 2023). The proposed bridge also creates economic anxiety, especially in the North and East. Some Tamils believe that they will not be able to compete with the enormous and dynamic Indian economy. Similar economic anxieties may also exist in the South. Therefore, the Sri Lankan government will have to deal with severe resistance if and when concrete actions are introduced to build the bridge. The Southern resistance will have the power to shut down the proposed project.

President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s political realities will also operate as a hindrance. First, I do not believe he likes the land connectivity idea. He is no less nationalist than J. R. Jayewardene. I believe that the agreement to undertake a feasibility study is a delaying tactic. He knows that he cannot antagonize India. Moreover, Wickremesinghe does not have a government of his own. He heads a government of the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP). Like many Sinhala nationalists, Mahinda Rajapaksa also has concerns about Indian hegemony and control. As a young politician, he believed India was coming to take the Sinhala land. Therefore, a political party headed by Mahinda Rajapaksa would not support a land bridge from India. The Sinhala resistance to the proposed land bridge can also potentially destroy Wickremesinghe’s electoral political ambitions. Therefore, as an astute politician, he will be cautious about the proposed bridge.

A significant player in this whole scenario is China. Despite Indian pressure, China had always maintained cordial relations with Sri Lanka and had invested heavily to bring Sri Lanka into its domain. It succeeded in this endeavor. The economic crisis weakened China’s image and its grip on Sri Lanka to a certain degree. However, the Asian giant remains a powerful player in Sri Lanka. China also knows that the proposed land bridge would strengthen India’s control while weakening China’s influence in Sri Lanka. Therefore, China will use its power and influence to halt the land connection project. A recent case in point was the Colombo Port’s East Terminal project. The India (and Japan) funded project was believed to be canceled in 2021 due to Chinese pressure. The canceled project was transferred to China’s state-run China Harbor Engineering Corporation. Therefore, the modern Ramsethu bridge would remain a mere dream. The bridge will not happen without fundamental shifts in regional geopolitics.