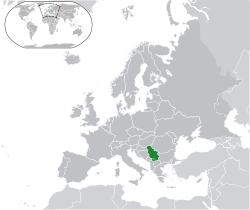

‘What Is Good For Serbia Is Good For Russia’ – Analysis

Whether or not relations with Russia are an obstacle to Serbia’s EU integration will depend, in part, on the EU’s ability to find a solution that will allow it to integrate both Serbia and Kosovo.

By Milan Milenković

After Serbia finalized cooperation with the Hague Tribunal in July 2011, and following violence in Kosovo in the same month, the EU’s conditionality towards Serbia has crystallized. During her visit to Belgrade in August 2011, Chancellor Merkel stated that Serbia must abolish the so-called ‘parallel structures’ in north Kosovo, allow EULEX to operate undisturbed in the entire territory of Kosovo and to continue dialogue with Priština.

The Serbian authorities, however, almost unanimously rejected the condition to cancel the parallel structures that present rare symbols of Serbian statehood in Kosovo. Merkel’s visit reminded Belgrade that Serbia’s path towards the EU was paved with numerous conditions, of which certainly the most problematic was the issue of Kosovo. The message is increasingly clear – the EU will not import new problems. All EU member states support the current negotiations on technical issues between Belgrade and Priština, under the EU’s patronage. Serbia is aware that its slogan, “both Kosovo and EU”, may soon echo back as an official stand from the EU as “either Kosovo or the EU”; or in the most extreme case, “neither Kosovo, nor the EU”.

In relations with the EU and major EU states, the Kosovo issue is the biggest problem for Serbia’s integration process. At the same time, however, this issue provides a crucial political link between Serbia and Russia. Recent violent events in Kosovo proved once again that situation on the ground is controlled by NATO and the EU, while Russia excluded itself from this process after it had withdrawn troops from Kosovo in 2003. In spite of not having direct influence in Kosovo, Russia is a crucial ally in Serbia’s attempts to prevent Kosovo’s statehood.

Recognition of Kosovo by Serbia – bad news for Russia

During the process of determining Kosovo’s final status, Russia – openly invited to help its “Orthodox brother” – insisted that any solution had to be acceptable to both parties, not imposed, and would be applicable to other regions of the world. An imposed solution would be the legitimization of NATO’s 1999 intervention that Russia “had so vehemently opposed”. Russia itself, however, was indirectly affected because of its own restless regions and those in its “near abroad”, particularly those of strategic importance. By standing firm, Moscow was “upholding” international law, and reinforcing the role of UN Security Council, thereby achieving important foreign policy goals.

After major Western states largely ignored Russia’s position – primarily because they considered its opposition to Kosovo’s independence as a kind of bluff – Russia used the ‘Kosovo precedent’ in its own backyard by recognizing South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states in August 2008. During the conflict, and in the period immediately after recognition, Russian officials often mentioned NATO’s 1999 intervention and the unilateral recognition of Kosovo by major Western powers as a prime justification of its actions.

The importance of the brief August 2008 war for Russia is best described by Aleksandar Lukin, who argues that that the military action “has undermined the model of Russian-Western relations that arose in 1990s and created a new situation in the world – one real, rather than declared multipolarity”. Lukin added that this “new situation in Georgia” was also a “discouraging lesson for some countries” regarding their behavior toward Russia.

If Serbia recognizes Kosovo, Russian crucial political link to Serbia – as the main opponent to Kosovo’s independence – would disappear and also the claim that Russia had merely “copied” the West’s behavior toward Kosovo would be diluted.

Another reason for Russia’s interests in Serbia not being conditioned to recognize Kosovo is the question of Serbia’s membership in NATO. The unwritten rule that one post-communist European country must first join NATO and then enter the EU, could be made a condition for Serbia before joining the EU. On the other hand, once being left without any chance to keep Kosovo, the Serbian authorities might completely turn toward European integrations, meaning that NATO membership might become more realistic and attractive as kind of a shortcut to the EU. During his visit to Belgrade in March 2011, Putin threatened the Serbian political elite with a Russian reaction if Serbia joins NATO, using the same rhetoric of the “Russian missile threat” as he used to warn the Ukraine about the consequences of its possible NATO membership. Russian officials repeated several times that if Serbia joined NATO, Russia would recognize Kosovo.

This kind of strong objection is rooted in several facts. The first is certainly the year 1999 and NATO airstrikes of Yugoslavia. If Serbia would join NATO, it would definitely legitimize that intervention. Membership of Serbia in NATO might lead to another serious “cooling down” between the “Slav brothers”; one that would be even deeper than after 2000, but probably not as serious as it used to be in 1948. Another reason for Russia’s objections to Serbia’s NATO membership is that Serbian military equipment is of Soviet/Russian origin and needs to be modernized. In a document created by the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, entitled “Programme for efficient use of Foreign policy on systematic basis as means for long-term development of the Russian Federation”, it was stated that Russia should continue its military-technical cooperation with Serbia.

The Konuzin effect

During the period of recent tensions in north Kosovo, Russia’s ambassador in Belgrade, Aleksandr Konuzin, stoked-up the anti-EU and anti-NATO mood. First, he described the actions of KFOR and EULEX as being part of “another huge anti-Serb campaign”, adding that the EU was blackmailing Serbia with Kosovo, and that its mission in Kosovo was “aggressively violating the international law and applying double standards in the implementation of the same principle”. Later on, in September, he held his now infamous speech at the Belgrade Security Forum, when he accused the Serbian authorities for being indifferent toward the issue of Kosovo, and that EU and NATO were opposing Serbia’s national interest.

Taking into account the public disposition in Serbia about European integrations, Konuzin picked the perfect moment to deliver the Kremlin’s message. In the last quarter of 2011, support for EU membership has never been so low; dropping below 50% in September for the first time since 2000. The Eurozone crisis, events in north Kosovo and the apparent conditioning of Serbia’s EU integration with the Kosovo issue will certainly not improve this percentage. Besides, it is not so difficult to trigger anti-Western sentiment in Serbia, with issues such as the ICTY, NATO airstrikes and Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence are sufficient for the “patriotically-orientated” part of the Serbian population to justify abandoning EU integration. Russian officials has used these sentiments quite well by always reminding about the 1999 NATO airstrikes, the unfairness of the ICTY towards Serbs and Russian support on the Kosovo issue.

How deep is Russian influence in Serbia?

Russia has a solid base from which to exert influence over Serbia, where public opinion considers Russia as Serbia’s main ally. Visits by the highest Russian officials always create more excitement than those from other states. A greater number of magazines in Serbia now write positively about Russia – its economic and political strength, cultural and religious heritage – whilst glorifying Serbian-Russian friendship throughout history. Political discourse is also very positive on Russia, especially from the parties to the right of the political spectrum, such as the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) and the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS). Indeed, other parties – like the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) and, in part, the Democratic Party (DS) – also share, but to a lesser extent, the tendency to evaluate cooperation with Russia as one of the most important priorities. Economic parameters show that Russia is the biggest import partner of Serbia, but also the country with whom Serbia has the largest trade deficit. Serbia is almost completely dependent on Russian energy, but they both share an interest in realization of the South Stream project.

Russian influence on elections was demonstrated during the extremey tight presidential elections of January-February 2008, when the Kremlin supported Boris Tadić because he was seen as a better partner for realizing Russian economic interests; namely, the energetic agreement that was proposed by Russia in mid-December 2007. Although the then leader of the SRS, Tomislav Nikolić, played the Russian card in campaigning, the Kremlin’s support went to his opponent. On that occasion, Putin sent Tadić a letter congratulating him on his fiftieth birthday, but also reminding him about energy-sector cooperation. This letter was used in Tadić’s election campaign as a clear sign of support from Putin. The signing of energy agreements between Russia and Serbia in Moscow took place between the two rounds of the elections, when besides Tadić and Koštunica, Putin and Medvedev were also present. This occasion definitely gave a small but much needed advantage to Tadić.

As in 2008, Moscow has its own calculations for the 2012 elections. On the third anniversary of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) in Niš at the end of October, Ambasador Konuzin appeared and even gave a political speech, whose content can be characterized as open support for the SNS. It seems that Moscow would like to see Nikolić as a leading figure in the next Serbian Government that would be a reliable partner for equal – and even favourable – treatment of Russian capital and investments, a Government that would not pursue NATO integration, nor be ready to give up easily Serbian interests in Kosovo. The slogan – “both Kosovo and the EU” – on which Tadić won the 2008 elections today seems quite unrealistic, and the current Serbian authorities are sending signals that they might be prepared to reconsider it. On the other side, the SNS are employing a metaphor of Kosovo and the EU as two sons whom Serbia will never give up. So far, voices from Moscow are supporting this policy.

Brussels on the move

Though the attractiveness of EU integration in Serbia rises when there are signs of progress, the magnetism of membership has been seriously shaken by the EU’s internal crisis, events in north Kosovo and frequent statements from EU member states connecting further progress to the Kosovo issue. There is some kind of consensus among the main political parties about joining the EU, after Nikolić managed to diminish the SRS as an electoral force. Serbia is the EU’s backyard, rather than an EU exclusive zone, so the future of Serbia’s EU integration will depend mainly on Brussels, and less on Moscow.

The integration of Serbia and the issue of Kosovo are of a great importance for the EU, mainly because EU credibility to act on the global stage depends on its ability to resolve problems in its own backyard, and Balkan instability will definitely affect the EU’s own stability. On the other hand, the Western Balkans, and particularly Serbia, are far from the main priorities of Russian foreign policy. Another factor is that EU member states are the most important economic partners for both Serbia and Russia. Whether or not relations with Russia are an obstacle to Serbia’s EU integration depends upon the EU’s capacity for creating a solution that will integrate both Serbia and Kosovo, whilst not in the process humiliating Serbia, nor pressing Belgrade to join NATO. The EU, however, lacks such a grand strategy; using instead the same pattern of pressure and conditions “spiced” with some “carrots”. Unfortunately the EU doesn’t have a coherent foreign policy, and most of the gaps that appear in relations with Belgrade will be filled with additional Russian presence in Serbia and beyond.

Milan Milenković holds MA in International Relations acquired at the University of Bologna and the Saint Petersburg State University (Interdisciplinary Research Studies on Eastern Europe – MIREES program). Also he graduated International Relations from the Faculty of Political Sciences in Belgrade and graduated at the Department for Advanced Undergraduate Studies – “The European Union and the Balkans Programme” of Belgrade Open School.

This article is published as part of TransConflict’s initiative, ‘Serbia’s Future on the Future of Serbia’, further information about which is available by clicking here.