China’s AIIB Voting Structure: South China Sea Pressure Point? – Analysis

Can the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s (AIIB) voting structure moderate Chinese territorial assertiveness in the South China Sea? It’s an intriguing idea.

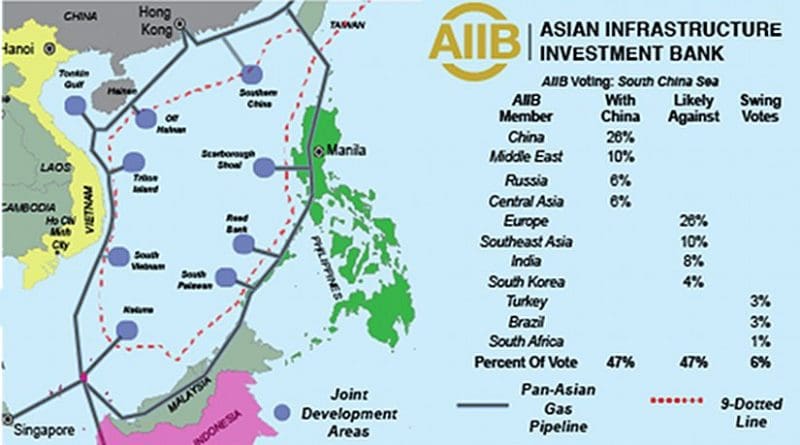

China holds veto power over Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), decisions. But other countries joining together can challenge it on issues like the South China Sea.

AIIB votes require a 76% majority. China holds 25% of the votes.

Despite this Chinese ‘veto,’ the AIIB’s other shareholders can make a very strong statement.

The reason: the AIIB’s professed independence from Chinese Communist Party control would be severely questioned if China overruled other AIIB members.

China won’t want that. On the other hand: the South China Sea is the ‘Elephant in the Room’ with the AIIB.

Given China’s increasing political isolation regarding its Nine-Dotted Line claim to the entire South China Sea, China could use a political escape hatch.

Suitably united, the AIIB’s other countries can provide it.

The escape hatch would be for the AIIB to fund infrastructure that can be used to service Joint Development Areas in the South China Sea.

These JDAs could be created in contested areas off Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia and Taiwan.

Oil, gas, methane hydrates, renewable energy and even fisheries within the JDAs could then be jointly developed by Chinese and Southeast Asian energy and fisheries companies.

The beauty of JDAs is that countries with contesting claims to a proposed offshore agree to set those territorial claims aside indefinitely while they cooperate to develop the resources within the contested areas.

Final territorial determination is postponed until far down the track. At that point the stakes are lower because the resources have been developed.

All countries in the region – including China — publicly support the concept of ‘joint development’ as a means of reducing risk of war in the South China Sea.

Given this, no one would be seen as backing down.

Successful JDAs exist all over the world. Three have operated successfully for decades in the Gulf of Thailand, adjacent to the South China Sea.

Therefore, Southeast Asia’s AIIB members, along with the AIIB’s European members and South Korea, could unite behind proposals for AIIB funding of the Association of Southeast Asian Nation States’ (ASEAN) proposed Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline (TAGP) and Trans-ASEAN Electricity Grid (TAEG).

If China dug in its heels in opposition, presumably due to conflict with its Nine-Dotted Line territorial claim, China could probably muster 47% of the AIIB’s votes in support of its position.

Support would likely come from Russia and the AIIB’s Central Asian countries and Middle Eastern countries.

European Union members of the AIIB would almost certainly unite in favor of JDAs, along with South Korea and the AIIB’s ASEAN members themselves. Together, these would amount to another 47%.

In other words, a virtual tie. Turkey, Brazil and South Africa would represent wild card votes.

In the end, such a vote would offer only a pyrrhic victory for either side. It could open up such large political divisions within the AIIB that the organization breaks apart. No one wants that.

To date, China’s underestimated the blow back from its geopolitical over-reach in the South China Sea. It’s been made worse by China’s domestic propaganda machine.

It’s been using the South China Sea as a distracting nationalistic lightning rod to shift attention from issues like needed reform of domestic residency laws (the hoku system) pollution and corruption.

The AIIB is an important symbol for the Communist Party that China’s emergence as a global player represents the ripening fruit of decades of personal sacrifice by the Chinese people.

While it’s an overstretch to call the AIIB it a ‘vanity project’ for China — it is something close.

Given this, China will work hard to keep controversial items off the AIIB’s agenda. This gives other members an avenue for getting China’s attention that other avenues — like appeals to UN Tribunals –haven’t.

Happily, the issue of the South China Sea need not be framed in such naked political terms. If the AIIB shies away from funding compelling infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia like the TAGP and TAEG, others can step in.

These include the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank, the Green Climate Fund and even Japan’s $200 billion export infrastructure fund — which alone boasts twice the capital of the AIIB.

If these organizations worked together to fund a common plan in the South China Sea and share funding, the AIIB’s hand could be forced. This would be particularly so if the AIIB were internally divided along the voting lines outlined above.

The big issue here isn’t a zero-sum involving one side or the other prevailing over the legality/acceptability of China’s Nine Dotted Line. The bigger issue is the preparation of the world economy for the 21st Century.

That means building out the infrastructure to enable more of Asia’s people to join the global economy and to enable Asia’s economies (like everywhere) to progressively decarbonize and more sustainably steward their resources like fisheries.

Given this, joint development in the South China Sea can set a crucial precedent benefitting everyone — particularly China.

Joint infrastructure in the region serving joint development areas would represent a crucial first piece of China’s own proposed One Belt, One Road concept of deepening cross-border interconnections between Asia’s economies.

Taking this a few steps further State Grid Corp of China, China’s electricity power line state champion, envisages a global electricity grid by 2050. That idea isn’t farfetched — at all.

Reaching agreement on core elements of such networks in the next 10 years can put the world economy on the kind of multi-decade economic trajectory that can increase wealth, pay the future income streams to fund aging global populations and solve climate change.

What’s needed is to get global institutions and the world’s countries in greater alignment.

They can start in the South China Sea.

The key question is where any Joint Development Areas would be located. If the whole of the U-shaped lined area were one big JDA then the Southeast Asian countries would join in. Instead China will stick to its position of ‘what’s mine is mine and what’s yours is half-mine’. So China will be happy to have JDAs off the coasts of Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines but not around the Paracels or off Hainan. A JDA within the claimed EEZs of the other coastal states would be seen by those states not as ‘joint development’ but the legitimisation by those states of China’s territorial claims – which they oppose.