Eisenhower And The Cold War – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Jeremy Black*

(FPRI) — Successful presidents do not need to come through the political process, but whatever their background, they need to be able to lead intelligently and to make sense of and mould the coalitions of interest—both domestic and international—that provide the opportunity to ensure the implementation of policy. One of the most impressive non-politician presidents was Dwight Eisenhower, the Republican president elected in 1952 and re-elected in 1956. A self-styled moderate conservative, Eisenhower provided an effective hard-edged moderation.

Eisenhower benefited from, and helped to mould, the conservative ethos of the 1950s. His re-election in 1956 with a margin of nine million votes displayed widespread satisfaction with the economic boom and social conservatism of those years. There was an upsurge in religiosity as church membership and attendance rose, and Eisenhower encouraged the addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance and “In God We Trust” on the currency. At the same time, Eisenhower left the New Deal intact and crucially extended it to incorporate African-Americans, even using federal forces to enforce the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.

The Eisenhower years were to be the background to modern America. In many respects, the new social and political currents of the 1960s were a reaction to this conservatism. Yet, to an extent that exponents of the “Sixties” prefer to forget, many of the developments of the 1950s had a lasting impact, notably the growing suburbanisation and car culture, the growing significance of the South and, far more, the West, and the willingness of government to challenge institutional Southern racism.

Moreover, Eisenhower understood the intertwining of strategy and policy and, in particular, the extent to which the military dimensions of strategy had to sit alongside civilian counterparts that strengthened the domestic base. His was a policy of robust containment—not the naïve optimism of “roll-back,” but a measured willingness to use force, the threat of force, and other means, to advance international goals, while at the same time protecting and strengthening the domestic base. The latter goal brought in a range of policies. Thus, the extensive and expensive Interstate Highway System was pushed forward by the Eisenhower administration in part in order to help speed the military response to any major war as well as to further economic integration.

Moreover, support for Civil Rights, which included the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 and the use of the military to enforce the Brown decision in Little Rock, reflected a range of attitudes, including Christian and Republican assumptions, but also the belief that racial discrimination was a national security issue. This was not only a point designed to thwart Soviet-bloc propaganda, but also a response to Soviet success in employing “national liberation” as a policy against the European colonial empires. J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI was far from alone in encouraging fears that Black activism could be exploited by the Soviet Union, and support for Civil Rights appeared a sensible as well as decent means to thwart this. Eisenhower continued Truman’s policy thrust, but took it much further.

Like most traditional Republicans, Eisenhower wished to reduce government spending. This affected his attitudes toward international relations and to procurement. Eisenhower sought to focus American strengths on the key theatre, which, to him, meant Europe. As a result, Eisenhower allowed the CIA to take a major role outside Europe, as in Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954. This looked toward its planning for operations against Cuba in 1961 and its significant part in strategy and operations in Southeast Asia.

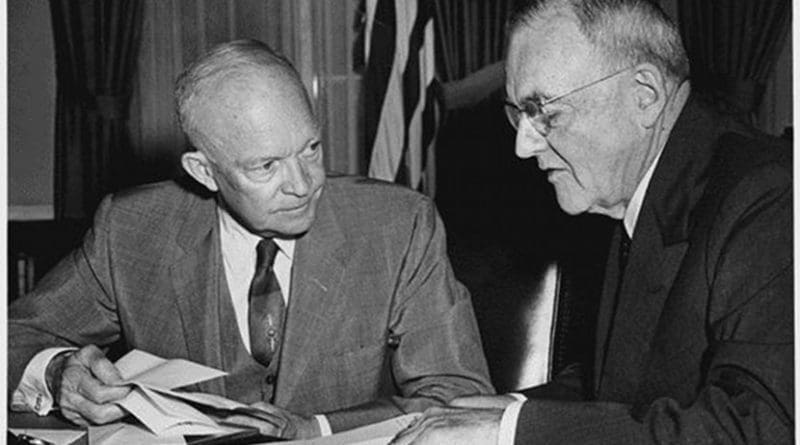

Eisenhower also displayed caution in pursuit of his foreign policy goals. He supported most of the financial burden of the French presence in Indochina by 1953, but was unwilling to commit the ground troops and air support that France sought. John Foster Dulles, the Secretary of State, wanted American intervention only as part of an internationalized war, but, first, the British and, then, Australia and New Zealand refused to participate. Moreover, Eisenhower did not wish to restart the Korean War in Vietnam. Thus, he avoided unnecessary escalation, even as the French faced defeat at Dien Bien Phu.

In Europe, there was no roll-back. The Americans were unwilling to intervene in Hungary in 1956 for a number of reasons—including UN reluctance to act; the simultaneous Suez Crisis that divided the NATO powers, especially the USA and Canada from Britain and France; the absence, due to Austrian neutrality, of direct NATO land access to Hungary; the fear of touching off a general war that would have involved nuclear devastation; the defensive military posture of NATO; and a lack of reliable information about options.

The absence of NATO action disheartened those who hoped to see a more active stance, and there were comparisons with the failure to act in defence of Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1948. Yet, Eisenhower was aware of NATO’s vulnerability and was concerned about the Soviet build-up of nuclear weaponry. In his inaugural address in 1953, Eisenhower referred to the risk of ending human life as a whole, while, at the Geneva summit in July 1955, Eisenhower emphasised that any nuclear war would, due to the windborne spread of radioactivity, end life in the Northern Hemisphere and thus ensure that, whichever power launched a nuclear attack would be destroyed by this very attack. Caution was to leave Eisenhower and his Vice President Richard Nixon vulnerable to attack over the “Missile Gap” alleged by the hawkish younger generation represented by John Kennedy, but Eisenhower proved a much more able custodian of the national and international interest than Kennedy with his fondness of rhetoric, greater embrace of risk, and folly.

Risk was an inherent consequence of containment and deterrence, but Eisenhower, with the example of 1940-1941 before him, saw isolationism as an even greater risk. Given the strength of the Soviet Union in conventional forces, this meant an emphasis on atomic weaponry. Its employment as a weapon of first resort was advocated by Eisenhower when he was NATO’s first Supreme Allied Commander and then as President. Aware of NATO’s vulnerability, Eisenhower felt that strength must underpin diplomacy for it to be credible. In December 1955, the NATO Council authorized the employment of atomic weaponry against the Warsaw Pact, even if the latter did not use such weaponry.

This was not unilateralism, but a matter of employing America’s strength in order to make its international stance and strategy credible. The cost of increasing conventional capability as a factor in encouraging a reliance on nuclear strength, as were the manpower implications, in a period of very low unemployment, of trying to raise larger armies. The need for the U.S., Britain, and France, already vulnerable in Western Europe, to deploy force elsewhere was also part of the equation. The maintenance of British and French power outside Europe became part of the strategy of containment.

Thus, nuclear weaponry appeared less expensive and politically more acceptable, as well as militarily more effective, either as a deterrent or, in the event of deterrence failing, as a decisive combat weapon. Building up nuclear strength appeared the best way to increase the capability in both respects.

This policy led to what was termed the “New Look” strategy, and more particularly, to the enhancement of the American Strategic Air Command, which resulted in the USAF receiving much more money in defense allocations than either the army or the navy. The deployment of the B-52 heavy bombers in 1955 upgraded American delivery capability, and a small number of aircraft appeared able, and rapidly, to achieve more than the far larger Allied bomber force had done against Germany in 1942-45. Thus, deterrence appeared both realistic and affordable, and it was hoped that nuclear bombers would serve to deter both conventional and atomic attack, although doubts were expressed about the former.

American allies faced difficult policy choices due to the Soviet threat, but more was at stake. Both Western Europe and allies in the Far East relied on the American nuclear umbrella. This reliance, however, made them heavily dependent on American policy. As at present, that implied an ability to rely on the calibre and consistency of American leadership. In the 1950s, part of the rationale behind the development of independent nuclear deterrents by Britain and France was the doubt that the USA would use its atomic weaponry if Europe alone was attacked by the Soviet Union; and there was also concern that the New Look strategy might lead to a diminished American commitment to Europe. Only an air force capable of dropping nuclear bombs appeared to offer a deterrent, but, as with the USA, the emphasis on the costly development affected conventional capability.

The development of long-range rocketry impacted this situation as well. Fortunately, Eisenhower was aware of the importance of technological development, and carefully prepared the United States for the missile age. Indeed, the Americans fired their first intercontinental ballistic missile in 1958, and were well ahead of the Soviets in that technology even as the Kennedy team and its media enablers attempted to spread panic with an imagined “missile gap.” Here as well, Eisenhower’s calm management style was underappreciated even as the United States and the West prospered under his leadership.

Although not a politician per se, Eisenhower succeeded because he managed to bring his unique outsider perspectives to bear on international and domestic problems. He was a thinking general adept at coalition politics, not an action man thinking with his pistol. He also displayed a strong commitment to sensible American leadership. The key strategic skills of prioritization, combined with a firmness and clarity of purpose that was not swayed by the affairs of the day very much characterized Eisenhower’s adroit and impressive presidency. It did not sparkle, and was all the better for that.

Jeremy Black’s books include Rethinking World War Two, Air Power, and Combined Operations.

About the author:

*Jeremy Black, an FPRI Templeton Fellow, is professor of history at Exeter University.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.