Global Child Mortality Falls Again, As Market Trade And Economic Globalization Spread – OpEd

By MISES

By Ryan McMaken*

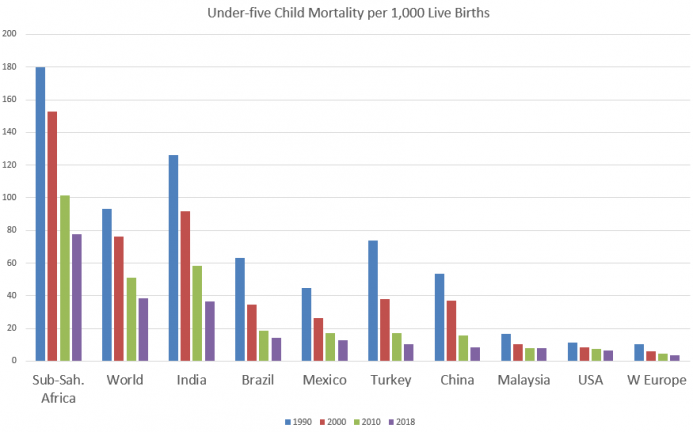

UNICEF this month released new data on infant and child mortality. As expected, the data shows continued declines in mortality for children, with most of the biggest gains coming in the lowest-income countries and in the developing world.

Of course, even in parts of the world where immense gains have been made, child mortality rates are still depressingly high, such as in Sub-Saharan Africa and in India where the under-five child mortality rates are 77.5 and 35.6 per 1,000 live births, respectively.

The region with the lowest mortality rate was western Europe with 3.7 per 1,000. That’s down from 10.4 in 1990.

In the US, the rate fell from 11.2 to 6.5 over the same period.

Meanwhile, some countries long plagued by poverty have nearly attained the sorts of child-mortality rates enjoyed in the first world less than thirty years ago.

For example, as of 2018, Mexico’s under-five mortality rate was 12.7. That’s only slightly above the USA’s 1990 rate of 11.2. Meanwhile, Malaysia and China have both pushed their child-mortality rates below what the first world was experiencing in 1990.

Infant mortality rates show a very similar trend, so on the whole, these number do show very real improvements.

To add context, however, it is important to consider abortion rates as well.

I know that in order to be intellectually fashionable, one is supposed to pretend that, say, an 8-month fetus is an un-person and that its termination is not to be included in health statistics in any way. But at the very least as at least an intellectual exercise, it is helpful to consult the available abortion-rate data, just in case infant mortality — as currently measured — is declining while abortion is increasing.

Moreover, under some regimes — in Cuba, for instance — according to the journal Health Policy and Planning:

Physicians often perform abortions without clear consent of the mother, raising serious issues of medical ethics, when ultrasound reveals fetal abnormalities because ‘otherwise it might raise the infant mortality rate.’ … At 72.8 abortions per 100 births, Cuba has one of the highest abortion rates in the world.

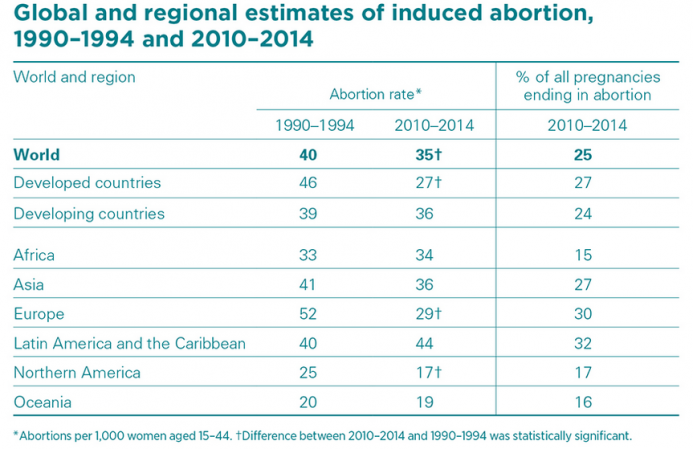

Fortunately, however, it appears that even if we consider abortion to be a type of infant mortality, mortality is indeed decreasing overall.

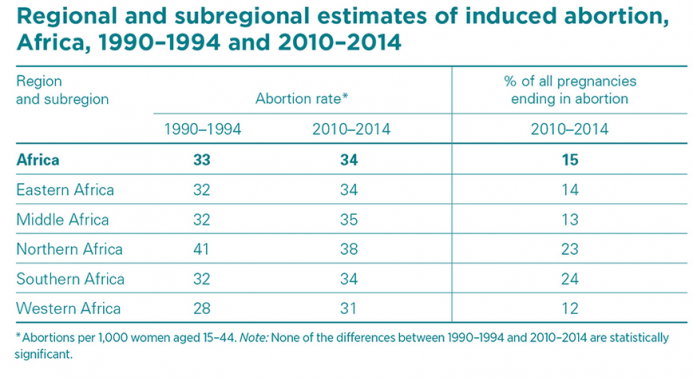

According to the Guttmacher Institute, even in Africa, which (along with southern Asia) has long been the poorest region, rates are stable:

Abortion appears to be on the decline throughout Asia:

The abortion rate also has declined in the “developed world” and in “Northern America.” Historical data suggests abortion rates in the US have been falling since the 1980s, and are now near a 45-year low.

Combined with a continued decline in child mortality, this should be considered progress indeed.

But what is the source of the progress? In the developed world, this is due to an increasingly globalized economic system that, for all its restrictions on markets, tolerates enough market freedom to allow for continued improvements in living standards. With more wealth comes more doctors, more hospitals, more supplies for sanitary medical services.

Some might claim “no, this economic progress is due to a larger welfare state and more socialism in the West.” What this claim ignores, however, is that in order to redistribute wealth it must first be created. And it can only be created through voluntary market transactions such as production, trade, savings, and other types of wealth building. If it is a policy goal of politicians to redistribute ten percent of the wealth of the “rich people,” that won’t do much good if the rich people aren’t that rich thanks to the impoverishment brought by interventionist and socialist policies.

In spite of the left’s relentless efforts to crush the capitalist goose that has produced so many golden eggs, good news is nonetheless found in the developing world because so much of it it has moved on from the protectionist, socialistic economies which dominated there prior to the 1990s. Thanks to global trade and increasingly free (although, regrettably, not unhampered) markets, Latin America, southern Asia, eastern Asia, and even Africa have moved toward becoming middle income countries.

What We Mean by Economic Progress

And make no mistake: when supporters freer markets call for more economic growth, the growth itself is not the end. The end goals are measured by metrics which include greater access to sanitation and clean water, rising literacy rates, and rising life expectancy.

Although it has become fashionable for anti-capitalists to deride as “money-obsessed” those who push for greater growth and greater income, the reality is that growth and income lead to things like healthier children.

Ludwig von Mises was addressing this shallow critique of markets when he wrote:

When the economists referred to progress, they looked upon conditions from the point of view of the ends sought by acting men. There was nothing metaphysical in their concept of progress. Most men want to live and to prolong their lives; they want to be healthy and to avoid sickness; they want to live comfortably and not to exist on the verge of starvation. In the eyes of acting men advance toward these goals means improvement, the reverse means impairment. This is the meaning of the terms “progress” and “retrogression” as applied by economists. In this sense they call a drop in infant mortality or success in fighting contagious diseases progress

*About the author: Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for Mises Wire and The Austrian, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has degrees in economics and political science from the University of Colorado, and was the economist for the Colorado Division of Housing from 2009 to 2014. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Source: This article was published by the MISES Institute