Asylum Processing At US Border: Legal Basics – Analysis

By CRS

By Ben Harrington*

Recent statistics and reports from the southern border show a sharp increase in the arrival of non-U.S. nationals (called “aliens” under governing law) who lack visas or other valid entry documents. (This article generally refers to such aliens encountered at the cusp of entry into the United States as “undocumented migrants” to distinguish them from those encountered within the interior of the country.) The trend includes a notable uptick in the arrival of unaccompanied alien children (UACs). Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials have opined that the current surge in undocumented migration could exceed the spike that occurred in 2019. As a result, questions have emerged about how the Biden Administration intends to address the surge and, in particular, how it plans to process the migrants’ claims for humanitarian protection from persecution or torture.

The humanitarian protections available to undocumented migrants at the border under U.S. immigration law include asylum (a discretionary protection from identity-based persecution abroad), withholding of removal (a mandatory protection from such persecution), and withholding or deferral of removal under the Convention Against Torture (a mandatory protection from government-sponsored torture abroad). Asylum is the most robust of these protections and the only one that offers a dedicated pathway to lawful permanent residence and citizenship. It also requires the lowest standard of proof but, unlike the other two, may be denied for discretionary reasons even to aliens who qualify for it. Despite their differences, however, all of these forms of humanitarian protection have similar implications for the regulation of undocumented migration to the border, as explained further below. (For brevity and per common usage, this Sidebar refers to the legal mechanisms for evaluating claims for any of these humanitarian protections as “asylum processing” or “asylum procedure.”)

For now, the Biden Administration has mostly retained a pandemic-related policy implemented by the Trump Administration that, on public health grounds, permits DHS to expel undocumented migrants at the border without any asylum processing. The Administration is currently reassessing that policy and has exempted UACs from it. How the Administration would approach asylum processing at the border without the pandemic-related policy remains unclear.

Why Is Asylum Processing at the Border a Challenging Issue?

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) generally prohibits aliens from coming to the border to apply for admission unless they first obtain visas or other valid travel documents. If aliens present themselves at a port of entry without valid travel documents, or if they cross the border illegally between ports, they are subject to removal from the United States. This general rule against undocumented travel allows government authorities to identify some aliens who do not qualify for admission before they reach the United States, thereby reducing the need for burdensome enforcement measures such as removal and detention.

Humanitarian protections create the principal exception to this general rule. The INA allows aliens to apply for humanitarian protections from U.S. territory, including at a port of entry or after crossing the border illegally. They need not obtain visas or any other form of pre-clearance first. Indeed, such forms of pre-clearance are generally unavailable. There is no asylum visa. Refugee processing is available from abroad, but only to a limited extent.

Thus, the legal framework calls for the removal of undocumented migrants unless they qualify for humanitarian protections. This framework creates a tension between border enforcement and humanitarian protections, as legal scholars have long noted, and gives rise to a formidable procedural challenge. The immigration system must distinguish between valid and invalid protection claims swiftly enough to discourage illegitimate claimants from traveling to the border and avoid leaving legitimate claimants in extended limbo, while also striving for fair and accurate adjudications. The Supreme Court made clear in 2020 that Congress has exceptional latitude to address this procedural challenge legislatively. Far more so than in the field of criminal procedure, which is subject to significant constitutional constraints, Congress may write the rules for asylum procedure at the border.

Asylum processing is only one component of the challenge posed by undocumented migration. Even without the need to evaluate asylum claims, the logistical and operational challenges of apprehending aliens encountered at the border, processing them for removal or release, and holding them during processing can overwhelm immigration officials during influxes. UAC processing at the border, for example, poses more of a logistical and operational challenge than a challenge of asylum procedure. As described below, the procedural laws for UACs focus on proper care and in most cases call for no assessment at the border of their entitlement to humanitarian protections. Yet, during heavy flows of UACs, immigration officials still struggle to transfer children out of temporary holding facilities at the border and into licensed shelters for children within 72 hours, as the federal law requires.

What Is the Statutory Framework for Asylum Processing at the Border?

In 1996, Congress amended the INA to create the expedited removal system. In conjunction with other statutes and court rulings, this system establishes a framework for asylum processing at the border that can be summarized as follows:

1. Screening. Asylum claims by undocumented migrants at the border should be screened for a level of potential merit called “credible fear,” and rejected if they lack such potential merit, before being referred to trial-type proceedings in immigration court. (A notable exception is that UACs from countries other than Mexico and Canada generally go directly to immigration court proceedings without a screening process, whether or not they make asylum claims.)

2. Detention. Asylum seekers must be detained during the screening process and, if they establish credible fear, may be detained or released on parole during subsequent immigration court proceedings. (Exceptions exist for aliens in family units, who generally are not detained beyond the screening process due to the Flores Settlement Agreement, and for UACs, who must generally be transferred from holding facilities at the border to licensed shelters within 72 hours, and then released to a suitable placement.)

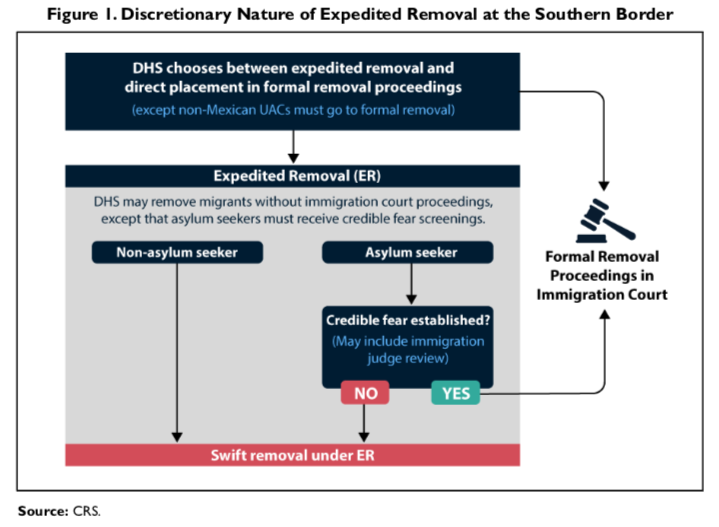

Expedited removal is a streamlined procedure that applies primarily to aliens encountered at or near the border. It stands in contrast to the standard process for the removal of an alien from the United States, which requires trial-type proceedings in immigration court—known as “formal removal proceedings”—in which the alien may present testimony and other evidence, including about whether he or she qualifies for humanitarian protections. Through expedited removal, DHS may swiftly remove undocumented migrants encountered near the border, so long as they do not establish credible fear or fall under other exceptions. Undocumented migrants who establish credible fear must be referred to formal removal proceedings.

Expedited removal does not apply to UACs, as mentioned above. Within three days of apprehending a UAC, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) must transfer the child to a licensed shelter run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). ORR is then required to seek a suitable placement for the child outside of federal custody, except in unusual cases. The child’s removal case, including any asylum claim, goes to formal removal proceedings. This framework for UACs has an important exception for Mexican UACs: unlike UACs from noncontiguous territories, CBP may allow Mexican UACs to return to Mexico voluntarily, subject to certain limitations. (Canadian UACs are rare but are also subject to the exception.) According to DHS statistics, given this exception, in practice the vast majority of Mexican UACs are quickly repatriated to Mexico while UACs from other countries often gain legal immigration status and rarely face removal within several years of arrival.

How Has the Executive Branch Implemented the Statutory Framework?

The INA framework leaves the executive branch with discretion on some essential points about how asylum processing works at the border, including the following.

First, DHS does not have to place undocumented migrants into expedited removal. Instead, under current case law, it can choose to place undocumented migrants directly into immigration court proceedings. (See Figure 1 below.) To do so, DHS typically releases the migrant from custody with a notice to appear in immigration court (“NTA”). The practice of releasing undocumented migrants with NTAs in lieu of placing them in expedited removal is sometimes called “catch and release.”

Traditionally, DHS has relied on this practice when heavy flows of undocumented migration strain the agency’s capacity to detain aliens during expedited removal and credible fear proceedings. For some periods of the Obama Administration (especially from 2014-2016) and the Trump Administration (especially during early 2019), DHS generally released family units apprehended near the border with NTAs rather than processing them for expedited removal. DHS statistics indicate that, largely due to immigration court backlogs, the great majority of family units processed in this fashion remain in the United States in “unresolved statuses” for several years.

The Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, or “Remain in Mexico”)—broadly implemented under the Trump Administration in mid-2019—introduced an alteration: under it, when DHS issued NTAs to some non-Mexican migrants in lieu of expedited removal, it required them to wait in Mexico during their immigration court proceedings instead of releasing them into the United States. There are questions about the legality of the MPP, and the Biden Administration has suspended new enrollments and begun to unwind it.

Second, DHS has significant discretion on operational issues, including where migrants are held during credible fear proceedings. The INA instructs DHS to conduct credible fear interviews “either at a port of entry or at such other place designated by [DHS].” Traditionally, DHS has conducted the interviews at Immigration and Customs and Enforcement (ICE) detention facilities in the interior after transferring migrants from CBP custody at the border. When conducted in this fashion, the credible fear process typically takes two to three weeks (including time for immigration judge review of negative determinations). Under the Trump Administration, DHS created two pilot programs known as Prompt Asylum Claim Review (PACR) and Humanitarian Asylum Review Process (HARP) to conduct credible fear proceedings in CBP custody on an expedited, five-to-seven-day timeline. The Biden Administration has terminated these policies.

Third, DHS may have some authority to trigger stricter screening standards at the border, but the extent of this authority remains unresolved. Credible fear is a “low bar,” as the Supreme Court has explained. According to GAO statistics from fiscal years 2015–2019, about 77% of asylum seekers and 87% of asylum seekers in family units establish credible fear. However, under the Trump Administration, the executive branch pursued various policies aimed at imposing stricter screening standards.

These policies can be categorized as follows:

Creating Asylum Ineligibilities. The INA authorizes DHS and the Department of Justice (DOJ) to narrow asylum eligibility by regulation. The Trump Administration invoked this authority in 2019 to issue a regulation that rendered most aliens ineligible for asylum if they reached the southern border after transiting through a third country without seeking protection there (the Transit Rule). For aliens ineligible for asylum under the Transit Rule, the regulation subjected them to a stricter screening threshold known as “reasonable fear” that applies to aliens who are eligible only for withholding of removal and Convention against Torture protections (which have a higher burden of proof than asylum). According to GAO statistics, only about 30% of asylum seekers establish reasonable fear. The Transit Rule is currently blocked by federal court order on the ground that it likely violates the INA, although the Supreme Court allowed DHS and DOJ to implement it during an earlier phase of the litigation. Federal courts also blocked a conceptually similar regulation that rendered unlawful entrants ineligible for asylum.

Safe Third Country Agreements. The INA also authorizes DHS and DOJ to render aliens ineligible for asylum by entering into safe third country agreements (STCAs) with countries that have “full and fair” asylum procedures. STCAs allow DHS to transfer asylum seekers to those countries rather than evaluating their claims in the United States. The Trump Administration created STCAs with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (in a departure from the statutory language, DHS called these “Asylum Cooperative Agreements”). Of these, only the Guatemala agreement was implemented, and only to a limited extent. The regulatory framework underlying these STCAs allowed DHS to remove an eligible asylum seeker at the screening phase of expedited removal, unless the asylum seeker established that it was “more likely than not” that he or she would face persecution or torture in the STCA country. This “more likely than not” standard was stricter than credible fear or reasonable fear. The Biden Administration has suspended these three STCAs (a more long-standing STCA with Canada remains in place but is undergoing legal challenge in Canada).

Pandemic-Related Public Health Bar. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump Administration implemented a policy that mostly shut down asylum processing for undocumented migrants at the border. This policy, issued by the Centers for Disease Control but implemented by DHS, is often called the “Title 42” policy because it purports to derive statutory authority from a public health provision of Title 42 of the U.S. Code. With few exceptions, the policy—as in effect during the Trump Administration—allowed CBP to expel undocumented migrants (including UACs) to Mexico or their countries of origin without any asylum screenings at all. The Biden Administration has exempted UACs from the policy but otherwise appears to have left it in place pending a reassessment of its merits. Ongoing lawsuits challenge the policy’s legality. Also, Mexican authorities have reportedly limited CBP’s ability to return Central American families to Mexico under the policy.

Regulatory Outlook and Reform Proposals

As noted above, the Biden Administration has terminated or begun to roll back the Trump Administration’s major pre-pandemic policies for processing asylum seekers at the border, including the MPP. The pandemic-related Title 42 policy, however, remains mostly in place for now (though not for UACs). Beyond that, the form that asylum processing will take under this Administration remains unclear. The President has signaled a commitment to expanding access in Central America to refugee processing and other forms of protection—measures the Administration hopes will eventually reduce the strain on asylum processing at the border by allowing people to apply for relief closer to home. Still, the concrete details of how asylum processing at the border will work in coming years are likely to emerge only after the termination of the Title 42 policy.

Proposals to reform asylum procedure at the border often focus on expediting the adjudication process in immigration court, with a goal of delivering definitive judgments more quickly. The proposals vary as to whether asylum seekers, including families, should be detained during these proceedings.

Somewhat along the lines of what the Biden Administration has proposed to do administratively, a different category of bill provisions would seek to reduce pressure on the border by expanding refugee processing in Central America. Some bills, including the U.S. Citizenship Act in the 117th Congress, would do this as an alternative to asylum protections (i.e., permitting but not requiring Central Americans to avail themselves of expanded options for refugee processing). Others would provide expanded processing as a trade-off that limits asylum eligibility at the border (i.e., requiring such aliens to make use of refugee processing options to a certain extent). Other ideas in this category include expanding immigration parole, special immigrant visa programs, and work visa programs for Central Americans.

*About the author: Ben Harrington, Legislative Attorney

Source: This article was published by the Congressional Research Service (CRS)