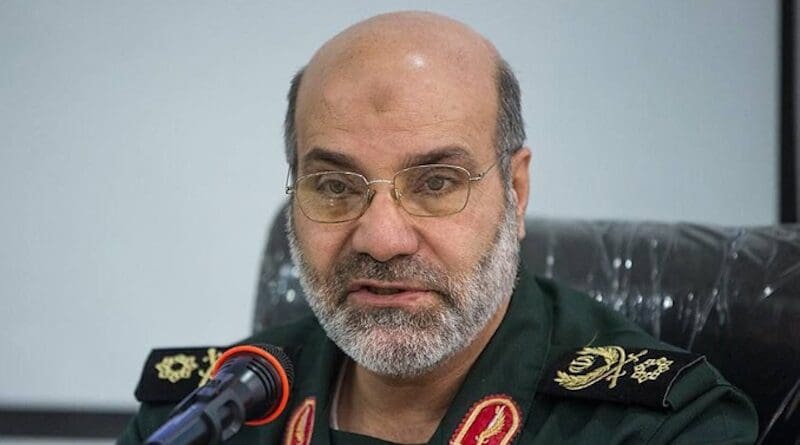

Who Was The Iranian Military Commander Killed In Damascus Strike? – Analysis

By Arab News

By Jonathan Gornall

Born on Nov. 2, 1960, in Isfahan, central Iran, Mohammad Reza Zahedi was a contemporary and close friend of Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the 62-year-old commander of the Quds Force, who was killed by a US drone strike in Baghdad, Iraq, on Jan. 3, 2020.

Soleimani had enrolled in what was then the newly formed Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, better known as the IRGC, in 1979, at the age of 22. Zahedi joined the IRGC the following year, when he was 20, at the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War.

Both men rose to prominence in the ranks of the special-operations Quds Force over the ensuing eight years of the conflict.

It was Soleimani who appointed Zahedi commander of the Quds Force Lebanon Corps in 1998, a position he held until 2002, and to which he was reappointed in 2008. He was responsible for organizing support for the regime of President Bashar Assad during the Syrian civil war, and overseeing shipments of Iranian weapons to Hezbollah via Syria.

Like Soleimani before him, on Monday night Zahedi met his end in a sudden and devastating missile attack, with no warning of his imminent demise. He was 63.

According to the IRGC, seven of its personnel, including Zahedi and three other senior officers, died alongside six Syrians in the attack on Monday, which targeted a military building next to the Iranian embassy in Damascus.

The three officers were named as Saeed Izadi, head of the Palestinian Division of the Quds Force in Beirut, Abdolreza Shahlai, commander of IRGC operations in Yemen, and Abdolreza Mosjedzadeh, who oversaw Iran-backed militias in Iraq.

Israel has refused to comment on the strike, even to confirm it was involved. The Iranian Embassy said that F-35 planes fired six missiles at the building. Later, The New York Times, citing unnamed Israeli officials who confirmed Israel carried out the attack, described the incident as “a major escalation of what has long been a simmering, undeclared war between Israel and Iran.”

In photographs distributed by the Reuters news agency shortly after the attack, the Iranian embassy — on the fence of which a large poster of Soleimani could be seen hanging — appears relatively undamaged. The building next door had been reduced to a smoking pile of rubble.

Reaction to the attack was rapid. Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad, who visited the site soon after, said: “We strongly condemn this atrocious terrorist attack that … killed a number of innocents.”

Iran’s mission to the UN condemned it as a “flagrant violation of the United Nations Charter, international law, and the foundational principle of the inviolability of diplomatic and consular premises,” and said Tehran reserved the right “to take a decisive response.”

Hossein Akbari, Iran’s ambassador to Syria, was unharmed in the attack. He told Iranian state TV that about seven people, including diplomats, had been killed and that Tehran’s response would be “harsh.”

Irani’s proxy in Lebanon, Hezbollah, also vowed to retaliate, saying “this crime will not pass without the enemy receiving punishment and revenge.”

There is a long history of embassies being attacked by enemies, but usually such assaults involve mobs of people or terrorist groups. In 1983, for example, 64 people lost their lives in a suicide-bomb attack on the US Embassy in Beirut carried out by a pro-Iranian group, and in 1998, 223 people died in simultaneous Al-Qaeda truck-bomb attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

It is highly unusual, however, for one state to attack the diplomatic premises or personnel of another and so the strike, not surprisingly, was condemned by nations including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Jordan, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar and Russia.

America did not condemn the attack outright but a State Department spokesperson said Washington was “concerned about anything that would be escalatory or cause an increase in conflict in the region.”

It was also quick to issue a statement claiming that “the United States had no involvement in the strike and we did not know about it ahead of time,” while also stressing that the US “communicated this directly to Iran.”

The regime in Tehran appeared to be unconvinced by this, however. On Tuesday, Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian said a Swiss diplomat representing US interests had been summoned by Tehran.

“An important message was sent to the American government, as a supporter of the Zionist regime,” Amir-Abdollahian said in a message posted on social media platform X. “America must give answers.”

The day after the attack, Israeli news media quoted Hezi Simantov, a well-connected Israeli correspondent and commentator on Arab affairs, who predicted that Iran was now “laying the groundwork to strike at Israeli diplomatic representations worldwide, in the Arab world, Europe or the United States or South America.”

The death of Zahedi, he added, “is a severe and painful blow to the Iranian regime, a matter in which the Iranians are more inclined to take revenge against Israel. We have already eliminated several of their senior officials since Oct. 7 on Syrian soil. This is the period when Iran wants to show that it is leading the Axis of Resistance.”

On Tuesday, Iranian state TV reported that the country’s Supreme National Security Council, chaired by the president, Ebrahim Raisi, had decided on a “required” response to the Israeli strike. No further details were given.

Zahedi was the third senior IRGC leader killed since the outbreak of the war in Gaza. His death is the most significant loss suffered by the Quds Force since the assassination of Soleimani four years ago and, before that, the death of Hossein Hamedani in October 2015.

At the time of his death, in an attack by Daesh in Aleppo, Hamedani was the most senior Iranian officer killed overseas since the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

In December, Sayyed Razi Mousavi, the IRGC logistics chief in Syria, who was responsible for coordinating the military alliance between Syria and Iran, died in a presumed Israeli missile strike on the outskirts of Damascus.

In January, Hujatollah Amidvar, an intelligence operative for the IRGC in Syria, was killed by an airstrike on a compound west of Damascus.

According to the Iranian Mehr News Agency, Zahedi held a series of significant roles within the IRGC. During the Iran-Iraq War, from 1983 to 1988 he commanded the 44th Qamar Bani Hashim Brigade, before going on to lead the 14th Imam Hussein Division between 1988 and 1991.

By 2005, he had become the IRGC’s head of ground forces, a post he held until 2008, and from 2007 until 2015 he was commander of the Syrian and Lebanese branch of the Quds Force, operating in Lebanon under aliases including Hassan Mahdavi and Reza Mahdavi.

Zahedi became the target of US sanctions in 2010, when the Department of the Treasury included him on a list of four senior members of the IRGC and Quds Force sanctioned “for their roles in the IRGC-QF’s support of terrorism.”

Described in a Treasury statement on Aug. 3, 2010, as “the commander of the IRGC-QF in Lebanon,” Zahedi was accused of playing “a key role in Iran’s support to Hezbollah.” He “also acted as a liaison to Hezbollah and Syrian intelligence services and is reportedly charged with guaranteeing weapons shipments to Hezbollah.”

The Quds Force has been active in Syria since 2011, when officers were deployed in an advisory role to support the regime of Assad, an ally of Iran, in the wake of the Arab Spring protests and uprisings in the region.

But, as the Council on Foreign Relations later reported, “as the discontent turned to civil war, the Quds Force served not just as military advisers but also on the front lines, fighting alongside Syrian regime forces, Lebanese Hezbollah militants, and Afghan refugees serving in IRGC proxy militias.”

It remains to be established beyond doubt whether or not Iran or its Quds Force was involved in the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel led by Hamas last year. IRGC officials “may have directly authorized Hamas’s assault and assisted in planning it, though Hamas and the IRGC have insisted that the Palestinian group acted independently,” the Council on Foreign Relations said.

It added that at the very least, Tehran “was likely aware of an impending attack that it had facilitated through decades of support for the Palestinian fighters.”

Either way, it added, “in the ensuing Israel-Hamas conflict, the IRGC has provided arms and other assistance to help its partners in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen to attack Israeli targets in solidarity with Hamas.”