Islamic Freedom In ASEAN – Analysis

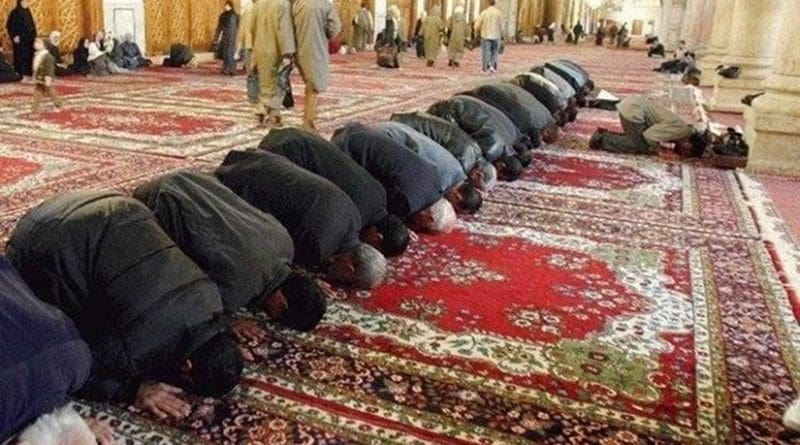

Almost half of the 629 million people living within the ASEAN region are Muslims. Within the ten countries of ASEAN, three countries Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, and Malaysia have Muslim majorities, and the remaining seven countries host Muslim minorities, ranging from 0.1% in Vietnam to nearly 16% in Singapore.

Due to the lack of any recent census data in many ASEAN countries, obtaining accurate figures of the Muslim population is extremely difficult, where estimates vary widely. In the Muslim majority states of ASEAN, Islam provides a source of political legitimacy for government and its leaders. Within the Muslim minority states, there are increasing aspirations for an Islamic society which today is expressed through the demand for Shariah (Islamic law), Madrasas (Islamic schools), Halal practices (what is permitted under Islam), and most importantly religious and cultural recognition.

Centuries ago Islam promoted both an enlightened intellectual and socially progressive culture which brought many societies to the forefront of art, medicine, scientific discovery, philosophy, and creative civilization.

However today we see a large proportion of the Ummah (Muslim community) living in poverty and isolated from the rest of the world community. Islam once the basis of a progressive society is now seen by many as backward and irrelevant. Most Islamic societies of today are struggling to keep pace with the rest of the world, creating a dangerously wide gap between Muslims and non-Muslims.

If we subscribe to Richard Florida’s concepts of socially determined creativity, then religious freedom would have great influence upon the level of a society’s innovation, and ability to solve the problems it faces as a community in a socially and spiritually wise manner. Within the Islamic world this would hinge upon;

- The freedom to practice Islam,

- The freedom to express Islam, and

- The freedom to produce new social intellectual output that will enable the evolution of a progressive Islamic society.

Thus Islamic freedom is an important determinant of how a society will fare intellectually, socially, and creatively in the future to enable that society to take a rightful place within the global community. We must also assume here that the very nature of Islam itself encourages the Ummah to engage other societies as has been practiced through Islamic history by the prophets, including the Prophet Muhammad himself.

Without engagement, Islam would have never come to the ASEAN region. However, the idea of “social creativity” and the invention of new ideas for social imagination vis-a-vis Islam is a problematic area as the political-theological and strict fundamentalist interpretation of Islam is adverse to “innovations” and consider too much creativity as dangerous and even to be rendered forbidden.

We saw that resistance in Malaysia with the Sisters of Islam, advocacy of gay rights, reinterpretation of Islam from feminist writers. There is also much debate about the compatibility of Islam to concepts of democracy, usually defined in ‘western ideological’ terms. Islam is basically considered as a concept opposed to the principles of democracy when Islam is viewed from through the lens of 9/11 ‘Islamophobia’.

Insurgency in Southern Thailand and Mindanao has added to the beliefs of many non-Muslims that Islam is an anti-democratic force. However these ‘radical extremist’ stereotypes held by many non-Muslims ignore the true motivations behind the reassertion of Islamic identity within the ASEAN region, where there is an exploration to merge Islamic philosophy with modern economic development, with the accompanying tensions and stresses this process produces for any developing society. Non-Muslims also ignore other non-religious factors such as history, ethnicity, poverty, and repression when stereotyping Muslims as a homogeneous group.

Table 1. The Approximate Muslim Population within ASEAN

| Country | Population | Muslim Population (%) | Muslim Population |

| Brunei Darussalam | 415,717 | 67% | 278,530 |

| Cambodia | 15,205, 539 | 4% (est.) | 608,622 |

| Indonesia | 251,160,124 | 88% | 221,020,909 |

| Laos | 6,981,166 | 1% | 69,811 |

| Malaysia | 29,628,392 | 60% | 17,777,035 |

| Myanmar | 55,167,330 | 15% (Est.) | 8,275,099 |

| Philippines | 105,720,644 | 10% (Est.) | 10,572,064 |

| Singapore | 5,460,302 | 16% | 873,648 |

| Thailand | 67,448,120 | 10% | 6,744,812 |

| Vietnam | 92,477,857 | 0.1% (Est.) | 92,478 |

| Total | 629,665,191 | 42% | 266,313,008 |

(Data primarily from CIA Factbook & www.islamicpopulation.com)

The

rest of this article will look at the current sitution of Islamic

practice and expression in the various ASEAN states, before looking at

some of the issues concerned with social output via potential new

interpretations of Islam.

Indonesia

There are over 200 million Muslins in Indonesia, representing almost 90% of the total population. The Indonesian constitution guarantees a secular society under the principles of Pancasila, the philosophical foundation of Indonesian nationalism. Until very recently the practice of Islam incorporated many local cultural habits influenced by Hinduism and Animism. Up until around the fall of Suharto in 1998, religious conversion, proselytism, apostates, and inter-religious marriages were totally unrestricted within the atmosphere of a secular society.

A large number of Islamic movements operated almost totally unheeded within the archipelago. However Islamic practice of rites and rituals began to change as more orthodox interpretations of Islam were propagated. Through covert and clandestine means, some groups within government opposed to the secularization of society like the Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI) and Religious Affairs Ministry have been reshaping discourses about what constitutes acceptable Islamic practice over the last decade.

A number of fatwas against secularism and liberalism were issued by the MUI in 2005 which began shaping specific and rigid Islamic practices across the country. This was accompanied by a growing intolerance towards alternative views of Islam. In 2008, the Religious Affairs Ministry, Home Ministry, and Attorney General signed a joint decree known as the Surat Keputusan Bersama, limiting the freedom of the Ahmadiyyah Movement practicing in an open manner.

Further evidence of this intolerance was seen in the savage attacks upon members of the Ahmadiyyah Movement in Pandeglang, in Banten Province back in February 2011, where the security forces were accused of having prior knowledge of the impending attacks and did nothing to prevent them occurring. The failure of the government to take legal action and restrain vigilante groups that violated laws and attacked other groups represents further evidence of this growing intolerance.

One explanation is that the growing rigidity of Islamic practice could have been allowed to happen because of Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s reliance on orthodox Muslim support in his cabinet. Islamic coercion has also increased in a number of provinces where Sharia law has been implemented, particularly in Aceh after the 2004 agreement. This has given local mayors immense powers to enact local regulations based upon their ‘moral authority’ in regards to Islamic matters like dress and modesty codes, and has often occurred arbitrarily without any shura or consultation, contrary to national laws made by an elected legislature.

There are a number of forces that look like restricting Islamic freedoms in Indonesia in the years to come. Conservative Islamic groups operating without any legal constraint are spreading the ideology of dividing the country into Darul al-Islam and Darul al-Harb, where Muslims are expected to strictly follow Islamic law.

Many MUI rulings are contrary to the constitution, and consequently not legally valid. However some provincial authorities are following these rulings stringently without any constraint. This is aiding the spread of an intolerant form of Islamic practice, evermore moving Indonesia away from being a secular state.

Malaysia

In Malaysia approximately 60% of the population are Muslim, who are predominately Malay with small numbers of Indian and Arab Muslims who migrated to the Malay Peninsula many generations ago. Article 11 of the Malaysian constitution guarantees freedom of religion, where Islam is the state religion.

Traditionally Islamic practice in the Malay Peninsula has been very liberal with many Muslim practices mixed with Malay customs dating back to the Srivijaya period, where superstition still plays some role in beliefs across some parts of the country, such as the symbolic circumcision of women. Many religious practices like the breaking of fast and Eid have turned into massive celebrations, taking on social rather than religious significance. Islamic affairs are a state concern in Malaysia and strictly controlled.

Women’s dress codes are followed almost without exception, through both regulation and peer pressure that has developed. State Islamic religious enforcement officers have the authority to accompany the police on raids to private residences and public establishments to enforce Sharia law, with particular focus upon violations in dress code, alcohol consumption, and khalwat, or close proximity between an unmarried man and woman. Free discussion about Islam is heavily suppressed. Mosques are regulated by the state and have minimal community participation within their organization. Imams are appointed by the state and Friday sermons are written by the state religious department. Consequently mosques are often used to convey government messages. There are restrictions on religious teaching, the use of mosques for community activities, and religious publishing.

Islamic schools whether public or private must follow state curriculum. These restrictions on Islam have evolved over the years partly due to the rise of a number of ‘deviant’ Islamic sects, like Al-Arqam that was banned in the mid 1990s.

The government has banned many deviations of Islam, often claiming them as a ‘threat to national security’, where only Sunni based practices are acceptable. People deviating from these teachings are given mandatory rehabilitation to maintain the ‘true path of Islam’ in the country. Shiite and Ahmadiyyah followers are forbidden to worship publically. As Islam ‘is a way of life’, much discussion about society and morals can be deemed to fall within the gambit of Islam, where discussion is therefore forbidden under the various state Shariah acts.

In effect, state fatwas cannot be challenged, although they may be contradictory from state to state, and sometimes in contradiction to the federal constitution. A National Fatwa Council exists within the Prime Minister’s Department comprised of state Muftis and other Islamic scholars. These fatwas are legally binding in Federal Territories. In Malaysia Islam is mixed with politics which has brought out many skewed debates about Islam, such as the introduction of Hudud laws and who has the right to use the word Allah. This has inhibited informed national debate about important Islamic issues, and often projecting Islam in a narrow and intolerant light.

The politicalization of Islam has also been divisive within the community where many mosque congregations have become politically polarized. The government controlled media is often used to attack any opinions contrary to the official view of Islam, as was seen with opposition politician Nurul Izzah Anwar’s comments on freedom of religion in 2012.

This all hints at an authoritarian view of Islam, where today there are visible trends towards further intolerance about discussion relating to the freedom to practice the Islamic faith within Malaysia. Issues relating to ethics, social justice, equity, corruption, the alleviation of poverty, and racial tolerance from any Islamic perspective tend to be glossed over in favor of more trivial issues that are holding the Malaysian narrative captive today. Although a flourishing Islamic banking sector exists in Malaysia, the rest of the economy has developed along occidental development paradigms.

There is actually very little Islamic influence upon policy and decision making which is centralized in Malaysia. This occurs where shura (consultation), and adab (meritocracy) are ignored, with little transparency and massive corruption. Within this framework, there is little real debate concerning social, spiritual, and economic evolution about what Malaysia should be like in the future.

Thailand

The Muslim community is rapidly increasing in Thailand, now representing around 10% of the total population. The Thai constitution provides for freedom of religion, where the government generally respects the various religious within the nation.

Muslims are clearly visible all over the country today. Many diverse groups comprise the Muslim community including the ethnic Malays along the border provinces with Malaysia, descendents of immigrants from Myanmar, Cambodia, South Asia, the Hui from Yunnan, China in Northern Thailand, and a growing number of converts from those who have worked overseas. Thai Muslims appear to be more assimilated with the general Thai community while Muslim-Malay population tend to be more resistant to assimilation as they have a distinct Malay culture and language.

This diversity can be seen in the individuality of Women’s Muslim dress around the country. Most Muslims in Thailand are Sunni following the Shaffie school, although there are a small number of Hanafi, and Shiites around the Thornburi area. Small deviating groups like Al-Arqam banned in Malaysia, flourish in Thailand. Military rule tended to repress the South for some years, where Thais liked to scapegoat and blame all Muslims for the troubles in the south. However Royal patronage of Islam due to the insurgency has given Islam much more exposure.

The image of a Muslim as a dark skinned Southern ‘khaeg’ has radically changed in Thailand. Consequently there is now much less employment discrimination against Muslims today and a number of Muslims have held high offices in government, police, and the military.

Today there are 38 provincial Islamic committees nationwide, which govern many local Islamic issues within their respective communities. Many committees operate Islamic schools which teach both the national and Islamic curriculum. There are a number of Ulama who tend to come from a select number of well known families within the various Muslim communities around Thailand. These families often operate private Madrasas (Islamic schools), some teaching both curriculum and some teaching only the Islamic curriculum. Some families operate Pondoks, numbering over 1,000, which just teach Islam.

The traditional Ulama in Thailand have great influence over how Islam is interpreted within their respective communities, where this tends to be a force for fragmentation rather than Ummah cohesion. Generally there is greater religious freedom in Thailand for Muslims than in the countries of ASEAN where Muslims are a majority. However most Ulama in Thailand have only undertaken Islamic studies at college or university and tend to take a conservative Islamic perspective about social issues.

This is even more so in the ‘Deep South’ where issues of Malay language, conflicts between civil and military policy, and ‘outsiders’ have led to the perception that the Central Government in Bangkok is intent on having a ‘war’ with Muslims, through ‘Siamization’. Thus through the Ulama system and issues of the ‘Deep South’ a very conservative approach to Islam is accepted, with suspicion about anybody bringing ‘outside teachings’. Muslims in Central Thailand on the other hand, especially around Bangkok, appear to be much more progressive and open to exploring integrative ideas that lead to community evolvement and assimilation with the rest of the Thai community.

Philippines

Muslims constitute approximately 10% of the total Philippines population. They are made up of various ethnic groups concentrated around Mindanao and surrounding islands of the Southern Region of the Philippines. Most are Sunni Muslims, but Shiites inhabit Lanao del Sur and Zamboanga del Sur provinces. Over the last decade there has been a rapid migration to the major cities of the Philippines, supplemented with Muslim converts returning from overseas.

Muslims now generally have a much wider presence in the country today, where more than two million Muslims live outside Mindanao with communities having mosques. Freedom of religion is guaranteed in the Philippines constitution which does not specific any state religion, and there is a clear separation of church and state. The National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF) is responsible for the implementation of cultural, economic, educational, and the Haj.

The government permits Islamic education in schools providing it is at no cost to the government. Muslims in the Philippines are divided by distance and language and thus not a very cohesive community. The only thing that many of these groups share is Islam. It is due to this reason that many Muslims feel marginalized, particularly in the electoral process. The organization of Islamic society is feudal in the rural areas where traditional Datu and Sultans still carry much influence.

Islam in the Philippines has absorbed many indigenous customs, where there is still some pre-Islamic birth, wedding, and death rites that vary across the archipelago. However more informed Islamic education over the last 30 years is slowly bringing a closer adherence to more orthodox Islamic practices. However there is a generational difference where young Muslims in Mindanao tend to see little relevance of the traditional social organization and customs in modern Islamic society.

A recent agreement between the Philippines Government and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) aimed at ending many years of insurgency will create a large autonomous region called Bangsamoro replacing the existing Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). Within this region Sharia law exists for civil matters, where some Sharia courts exist, although understaffed.

Although the government is very tolerant towards Muslims, there is still some cultural discrimination by private employers and landlords who stereotype Muslims. Consequently some wear western clothing and take on western names to get jobs.

Islamic freedom is probably most curtailed through the very high incidence of poverty in the Southern Philippines, where according to a 2009 US State Department report on religious freedom, many Muslims complain of economic discrimination. In addition, the Muslim separatist conflict has caused great hardship on Mindanao’s 15 million inhabitants with over 120,000 deaths since 1972. This may not end as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, a breakaway group from the MILF have vowed to keep fighting. Poverty and conflict has forced hundreds of thousands of Muslims to leave their homeland and establish new communities.

Myanmar

Due to the lack of any census and the exclusion of the Rohingya people as citizens of Myanmar, it is extremely difficult to estimate the Muslim population within the country. The Rohingya numbering almost one million people are concentrated in Northern Rakhine State. Yunannese Chinese Muslims live in the Shan State, the Pashu, or Malay Muslims in Southern Myanmar, and various groups of Indian Muslims are living in the cities.

Although various ethnic groups make up the Muslim population, they tend to be seen as a homogenous group from the Myanmar Buddhist perspective. The concept of freedom of religion has been upheld under three successive constitutions. Although Buddhism is recognized as the as the religion practiced by the majority under Section 311, under section 153, sub-section b, citizens of Myanmar are allowed to practice their culture, traditions and profess the religion of their choice, where Islam is specifically recognized under Section 361.

However in practice successive Governments in Myanmar have attempted to “Burmanize” minority ethnic groups which has affected Muslims greatly. Evidence indicates that equal rights have not been given to Muslims. For example, the national media refers to Muslims as Kalars (dark colour), a derogatory remark in Myanmar.

Over the years since colonial times ‘Indophobia’ about Indian immigrants has become a deep ‘Islamophobia’. Muslims have been criticized for not integrating themselves into general Burmese society and thus generally blamed by the Buddhist majority for causing civil unrest.

Many Muslims exist within Myanmar within a legal limbo of no citizenship. Muslims have basically been marginalized. Muslim-Buddhist relations have become very tense over the last few years leading to riots breaking out in Rakhine in May, June, and October 2012. This was triggered by the rape of a Buddhist girl by three Muslim men which led to escalating retaliation on both sides, where the Myanmar authorities were criticized for standing by and not controlling the violence.

However beneath this trigger, the underlying causes of the violence are deep running issues. The rhetoric by nationalist groups and politicians, the role of the Rohingya leaders, poverty, illiteracy, and general intolerance by the security forces, have over a long period of time created tensions between the government and minority groups.

An All-Myanmar Muslim Association has recently been formed by five groups to try to unite the voice of the fragmented Muslim populations within Myanmar. With Myanmar’s quest for democratization, the future treatment of Myanmar’s minorities will be crucial. To date Aung San Suu Kyi has not articulated any clear stand on the issues of Muslims in Myanmar, except to criticize the proposed two child limit for Muslim families, while military operations against minorities seems to be widening. Myanmar’s Muslims continue to be marginalized and pushed to the fringes of Myanmar society.

Cambodia

There are perhaps just over 600,000 Muslims, mainly of Cham dissent within the Kompong Cham region, and ethnic Malay in towns and rural fishing areas in Cambodia today.

During the Pol Pot years (1975-79) the Muslim population decreased to under 200,000 from 700,000, where all mosques were used for cattle and pig rearing, while Islamic materials were destroyed. Many Muslims were forced to marry those of other religions, forbidden to practice their faith, and even forced to work tendering pigs, etc. Most imams and religious teachers were killed during this time, and since this period, the Muslim community had to re-educate members of the community in matters of Islam through the help of both Cambodian Government and international assistance.

There are reports by researchers of good harmony between Cambodian Muslims and the majority Buddhist population. It has been suggested that mutual suffering of both communities under the Pol Pot regime had assisted in developing great community tolerance for one another. The Cham were called Khmer-Muslim by the late HM King Norodum Sihanouk, symbolizing all Cambodians’ equality under the law and state. A Council for Islamic Affairs and Multi of Cambodia was re-established in 2000 with the job to manage Islamic issues from a top to local level perspective. Each Muslim village has a leader or hakim recognized by the Multi of Cambodia and Minister of Cult and Religion.

There are today many Muslims in the Cambodian Government with an advisor to the Prime Minister, 2 senators, 5 parliamentarians, 5 deputy ministers, 9 under secretaries, 1 vice governor, some army generals, and a number of provincial, district, and community officers. Muslims are able to freely express their culture, where the Cham or Khmer Muslims tend to dress slightly different to Buddhists. They speak their own language and write Jawi, with a number of different Muslim sects like Salafi, Shiites, Kalafi, and Tabligh able to practice freely.

However many Muslims in Cambodia today are unable to read Arabic and have limited Islamic knowledge. Scholarships are given both by the Cambodian Government and overseas NGOs for Cambodian Muslims to study in Thailand, Malaysia, and the Middle East.

Singapore

About 15% of Singapore’s population are Muslims. Freedom of religion is guaranteed under the constitution in Singapore, however religious rhetoric and practice must not breach public order.

Article 152 of the Singapore Constitution recognizes Malays, who are predominately Muslim as the indigenous people of Singapore. Under Article 153 of the Constitution, the Singapore Government maintains a semi-official relationship with the Muslim community through the Islamic Council of Singapore (MUIS), which advises the government on the needs of Muslims, drafts approved Friday sermons, oversees mosque building paid for out of Muslim salary deductions, and operates the shariah court.

In Singapore the Religious Harmony Act prevents the mixing of religion and politics in public comment. The discussion of Islamic issues are banned in public debate with Muslims being asked many times to practice self censorship in what they say. The Singapore Government allows Muslim at attend Madrasas in lieu of public education but quotas are strict. Most Muslims are Sunni, following the Shaffie school of thought, but there is no restriction on Shiite and Ahmadiyyah practices.

However the government policy of promoting Singaporean nationalism has affected Malay-Muslim culture greatly in Singapore. The government strictly enforces ethnic ratios in public housing estates which has broken up Malay Kampongs and lifestyle, so to some degree weakening Muslim cohesion. The banning of the Muslim headscarf in 2002 and the development of co-religious worship centres housing Islam, Buddhism, Taoism, and Hinduism are further measures that that are aimed at promoting community integration, at the cost of ethnic identification.

Singaporean Muslims would argue that harmony has been promoted through suppression of religious rights. Critics of the People’s Action Party Government have pointed to the Islamophobic and Chinese chauvinistic rhetoric of its leaders over the years, where Chinese culture and language has been promoted over Malay-Muslim culture. This has left Malay-Muslim as an underclass in Singapore, where due to the structure of the electoral system, no Malay candidates without establishment support can ever win due to no more than 25% Muslim concentration in any single electorate.

In addition there have been complaints within the Muslim community that university places for Muslims are restricted to only 10% when the Muslim population is around 15%. In addition sensitive positions in the military are not held by Malay-Muslims in Singapore.

Conclusion – This is an ASEAN Problem

How free is Muslim society to evolve through new ideas based upon Islamic foundations? Different ASEAN states have responded differently to the Muslims in line with the nature of their respective cultural, political, and economic situations.

Poverty, literacy, education, displacement, feudalism, unemployment, suppression, and control is dispossessing Muslims within ASEAN. Government and Ulama are trying to develop theocracies based little social and economic research and knowledge, and promote ritualized conformity instead. Islamic interpretations are patterned into rigid thinking and ideas where new interpretations are frowned upon. This seems to be symptomatic of Islam being utilized as a power structure to reinforce a certain social status quo to maintain an hereditary or political grouping, rather than a means of advancing society’s interests.

Islam is a source of power in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, while it is feared and repressed in Myanmar and Singapore. The ‘culture of Islam’ is preventing the young think of modern contextualizations of Islam and engaging society with new solutions to existing problems. Young educated intellectuals are repressed by systems that place narrowly educated Ulama in authority, who feel a threat from new ideas to their power over the community.

Islam is heading into a reformation, rather than an enlightened renaissance that could potentially inspire the ASEAN community. Islam promotes the accumulation of knowledge, enterprise, and innovation, however the current direction of Islamic doctrine within ASEAN appears to be the opposite. Social innovation is being stifled, which is needed for community evolution. Much teaching of Islam focuses upon obedience to the rights of Allah (Huquq Allah) through the rites and rituals of the pillars of Islam, profession of faith, prayer, fasting, giving alms (zakat), and performing the pilgrimage.

The rights of humans (huquq al-nas), and the common rights of Allah and humans are most often ignored in Islamic teachings (huquq al-ibadah). The handling of social matters and organization has been left to rigid interpretations of Islamic law (Fiqh), most often in a narrow and literal sense. The rights of Allah have been taken over by leaders and rulers who have interpreted Shariah as the right to punish those who don’t follow; putting the rulers in the place of God, who cannot be questioned. Often practices that are culturally different are prohibited even though they are not forbidden in Islam, as it is assumed that non-mention infers practice is haram.

As we know, there is no single interpretation of Islam. Different interpretations of Islam have lead to war and hate among the Ummah itself. Within ASEAN, Islam has been evolving under different influences, over different time periods. We have seen the animist-syncretist Islam of Indonesian and Malaysian pre-Independence, influenced by the Hindu-Buddhist tradition, still practiced widely.

Next the beginning of the meeting of secularism with Islam in British and Dutch colonialism, and next the advent of the influence of the Iranian Revolution and the Ikhwanul-Muslimim of Anwar Sadat period. The 1980s saw the “Islamization of the Mahathir era” as a response and neutralizing agenda of the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. Now in Malaysia we see the promotion of Malay-Muslim ideology to uphold pro-”Bumiputeraism”. Culture and ideology has shaped the spiritual ideology and way Islam has been practiced to govern lives within the ASEAN region.

Thus the argument that there is only one interpretation of the Shariah doesn’t hold. Islam has always been changing according to internal power aspirations and perceived external threats. This has been at the cost of Islamic freedom as provided in huquq al-nas, which is hindering the development and evolution of Islamic societies, skewing concepts of democracy as being contradictory to Islam.

Islam within ASEAN society has clung to the contextual principles of Shariah important to the economic realities of past societies, and failed to look at the whole intended message of Islam to humanity within the context of today’s issues and challenges. This requires a new coherent and systematic methodology of interpretation of the totality of the Qur’an and Sunna, rather than the arbitrary and selective interpretations that are made today. Muslims today exist in multi-religious nations which are engaged with the global environment of interdependence. Mutual influence cannot be escaped and new ways to engage this situation are required if the Ummah is to be relevant in this global environment.

Traditions can change as long as these new traditions and cultures don’t infringe upon the doctrines of Islam. And this is where freedom is most needed, for scholars and community to develop their respective societies within the concept of clearly defined objective of Al-Falah (economic, social and spiritual prosperity).

Shariah without al-ilm (the gathering of knowledge), shura and adab (meritocracy) is not a complete world of Islam. Thus a complete Islamic view of society still requires intellectual development. There are no contradictions with democracy, only that democracy in Islam must go down to the family, the village, then only to the community, and society.

Democracy in Islam is indeed a much more ‘grassroots’ or ‘bottom up’, and consequently much more comprehensive than ‘westernized’ views of democracy. According to Islamic doctrine of shura, this model is mandatory to develop, but one feels this would be too threatening to the status quo of ruling elites around the world. Islam is the only faith that enshrines democracy into society, supported by adab, which is suppressed by ruling elites in the region. This repression of Islamic freedom is indicated by the steady fall of Malaysian universities in the various world rankings over the last decade, where the majority of academic positions are reserved for Bumiputera-Muslims who serve their masters rather than produce innovative ideas.

Today in the Malay-Muslim states and regions of ASEAN strong cultural power-distance relationships are repressing Islamic development and the opportunities for the younger generation to be creative. The stifled evolution of Islamic society will continue to increase the economic and social divide. In many cases young Islamic intellectuals are not critically evaluating the doctrines of Islam, but rather applying them as codified law, regardless of context.

The emphasis of those who control Islam has been to produce conformity of individuals at the cost of focusing on how society could be structured and organized to better obtain a defined vision of Al-falah. But new ideas within this context become viewed as liberal Islam, often shun by traditionalist Ulamas who have tended to focus upon the ritualistic fardhu ain (individual’s responsibility to perform religious duties), while basically ignoring the importance of fardhu kifayah (a collective responsibility for both social and spiritual development). Education is the key here. Islam is about God, community, and individual, making commentary about the dynamics of how these relationships should interrelate. Therefore Islam must be rebalanced to reflect the whole meaning of the Qur’an and Sunna.

Consequently Shariah should be framed in the positive rather than the negative. It must be based upon the reasoning that the Qur’an says humanity is gifted with, and reasoning needs debate and the exchange of different views in order to determine what is best for society. This is the power that the Qur’an has given to the Ummah. For this to occur, the Shariah must be looked at openly, rather than any one interpretation imposed on society in the name of Islam.

Shariah interpretation must be undertaken without feudal tribalism and the power-distance accorded political elites with a monopoly of interpretation and power. The concept of Al-falah needs clear definition as to what society’s objectives within the gambit of development should really be. This requires changing the development paradigm if it is to be integrated with the concept of Al-falah and defined as national, regional, and community development objectives. Then only can a really effective social economy reflecting the values of Islam can be built. This requires recognition that the element of greed cannot be allowed to dominate the market mechanisms, and that there are more important objectives of equity, community, harmony, equal opportunity, and compassion which must be reflected within the economic system.

However a counterforce to Islamic tyranny exists through the means of the new media technologies which will play an important role in shaping Islamic consciousness within the 21st century. This will bring the issues of poverty, alienation, marginalization, elitism, and feudalism to the fore where they must be addressed if governments are to survive. This arising global Islamic consciousness may expedite change in the old structures that currently exist in the name of Islam.

Islam contains many exciting socio-economic concepts which could potentially hold solutions to some of the world’s structural economic problems. But conformity to a narrow rather than holistic view of Islam as a social mechanism is holding back social innovation from the Ummah within ASEAN. The Islamic elites within ASEAN have intentionally and unintentionally stifled social development. The ability of the region’s academics and policy makers to come up with really creative solutions to community problems is suppressed, while societies major problems have just been swept aside and dealt with through denial and punishment. Compassion and love as the basis of society has been glossed over for hate and prejudice which is insulating society from being able to evolve and contribute to the world community.

The concept of sustainable society is embedded within the Al-Qur’an. These meanings are not being allowed to come out and be canvassed as potential solutions to the world’s crippled economic and financial system, climate, change, and global warming. There are no reasons why Islamic social and economic solutions cannot be put forward as solutions to societies where Muslim populations is a minority. Social segregation, confidence and the framing of these proposals seem to be the barrier.

And if the Qur’an is a universal text, then it is the obligation of Muslim intellectuals to bring the wisdom of the Qur’an to the rest of the ASEAN community. Muslims have a responsibility to contribute to society as a whole, not just the Ummah, as many Ulama seem to believe. This reinterpretation of ethics, society, economy, and sustainability would not only benefit Muslims but may also have a lot to offer secular societies, if the wholeness of the Al-Qur’an’s social message can be put on the table for discussion.

If the context of Islamic interpretation is not flexible to serve the needs and aspirations of the Ummah, only to serve those in power; then there is great risk that Muslim society in ASEAN will not be able to solve their social problems in any permanent manner to achieve their economic, social and spiritual needs.

The 21st century requires a different style of Islamic evolution as opposed to the 80s revival of Islam which incorporated Reaganomics and Thacherist ideologies, or the interpretation of Islam last decade to respond to the Bush/Wolfowitz doctrines coming out of 9/11. There are risks that these societies will lack the necessary skills conducive for creativity and wisdom at a community level.

In such a scenario, ASEAN Muslim society may find it difficult to engage the rest of the world socially and economically. It is still the secular state that determines how ‘free’ Islam will be, and how ijtihad or the power of reason will be shaped as a central approach to creativity within the social realm. Due to the large proportion of Muslims within ASEAN, this is not a Muslim problem, but an ASEAN problem.