Somalia’s Membership To East African Community (EAC): Gradual Approach Is Best After Institutional Reforms – Analysis

Summary

Is Somalia ready to join the East African Community (EAC)? Would Somalia’s political, economic, and social fragility put it in a weak position and negate any benefits derived from the EAC? Given inadequate labor export capacity and critical domestic skills shortages, would the much-touted labor mobility between the EAC members help Somalia? Somalia might be aligning its domestic regulatory practices in services with those in EAC, but does Somalia have the regulatory institutions required by the EAC? Somalia is not ready for deep integration into the EAC Community. Still, after reforming its national institutions, a variable geometry—incremental approach to EAC membership could usher in new fast-tracked reforms for Somalia regarding financial regulations, healthcare modernization, and small industry development. Given weak institutions, Somalia can be given longer transition periods to conform with EAC regulatory requirements.

This article will review Somalia’s readiness for the EAC in light of the challenges Somalia is facing and will recommend that Somalia not join the EAC now. However, after reforming its institutions, gradual approach is the most prudent way to integrate Somalia into EAC.

Brief History of EAC

The Treaty for reestablishing the East African Community was signed by the heads of state of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania and entered into force on July 7, 2000. Two new members, Rwanda, and Burundi, acceded to the Community in 2007 and the Republic of South Sudan in 2016, bringing its membership to six. In 2022 the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was added, opening the Community to the ports of Atlantic Ocean trade.

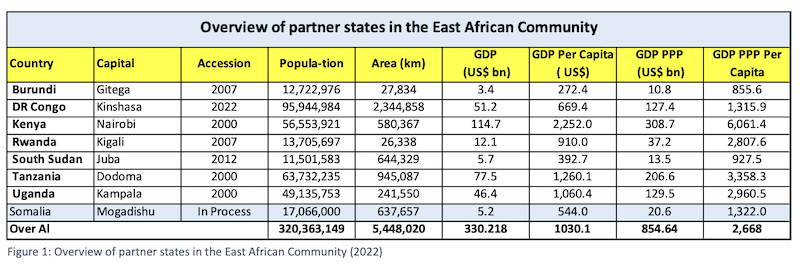

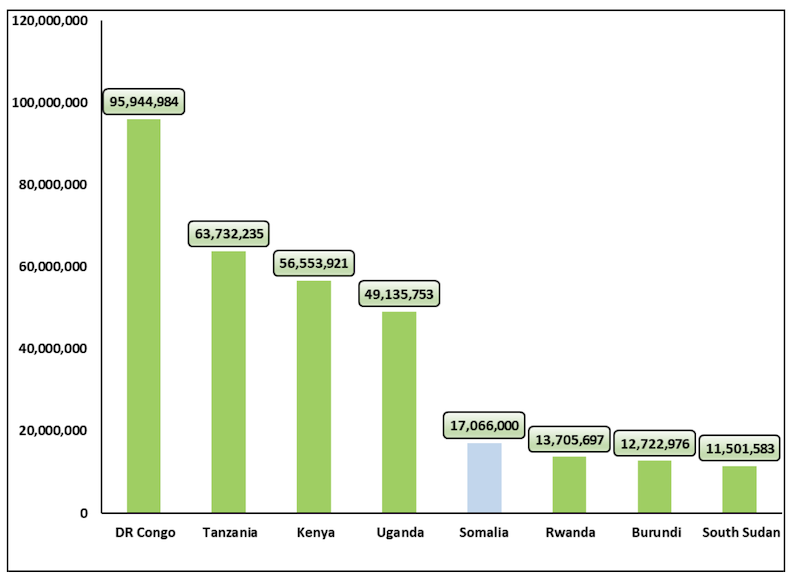

As the following chart shows, based on 2022 estimates, Somalia’s population will be the fifth largest of the Community, with one of the smallest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of US$544. Overall, with Somalia joining, the Community will have a population of 320 million with a whopping GDP of US$330 billion (US$1,030 per capita).

Figure 2 shows the population distribution of EAC’s current members with Somalia. (2)

The Community established a Customs Union in 2005 and Common Market in 2010. It is in the process of establishing a Monetary Union by 2023, but this could be delayed given the various financial regulations it entails. The Community’s ultimate objective is launching a complete political Union—a “Political Federation of the East African States.”

Even the more established organizations like the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Southern African Development Community (SADC), and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) do not have a provision for political union in their founding treaties. By its integration process, and objectives, the new EAC typifies the regional blocs that the new wave of regionalism has spawned. It takes for its model the EU and has adopted the EU’s institutional framework—it is highly institutionalized.

Somalia’s EAC Application

Somalia applied to be a member of EAC in 2012; however, that application was rejected. Again in 2019, Somalia submitted its application for EAC membership but was put pending until it was again revisited when President Hassan Sheikh Mohmoud was elected in 2022.

On January 25, 2022, “…officially launched the verification mission to assess the Federal Republic of Somalia’s readiness to join the Community.” (3) The verification process was scheduled from January 25 to February 3, 2023, where the EAC technical team would engage the various sections of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS). On June 1, 2023, EAC Heads of State deliberated & adopted the report verifying the application of the Federal Republic of Somalia to join the EAC and directed the EAC Secretariat & Council to commence negotiations with Somalia immediately and report to the next Ordinary Summit.

As per Article 3 (2) of the Treaty Establishing the EAC, when a partner state applies to join the Community, the following factors are considered:

- Geographical proximity to and interdependence between it and the Partner States.

- Acceptance of the Community as set out in this Treaty.

- Adherence to universally acceptable principles of good governance, democracy, the rule of law, observance of human rights and social justice.

- Potential contribution to the strengthening of integration within the East African region.

- Establishment and maintenance of a market-driven economy.

- Social and economic policies being compatible with those of the Community.

Somalia has a geographical proximity and interdependence between Somalia and the partner states; however, Somalia, as a fragile state, has a host of domestic challenges. The low-income and inadequate implementation capacity biases would be amplified if Somalia joined the EAC. In terms of the economy, Somalia would need to be careful not to have overly optimistic expectations for trade liberalization and to consider the benefits and implications of EAC membership, especially given the country’s underdeveloped institutional and physical infrastructure. The advantages of trading in products will probably be realized by importing goods that one cannot create effectively. Somalia will require a broader regional market to lessen its reliance on imports from non-East African countries, and EAC factor mobility norms may help with factor shortages. Somalia will probably continue to follow EAC rules for some time as well. Additionally, integration must be weighed against the dangers of enduring regional oligopolistic rents.

Most of the current EAC members are at the bottom of the world ranking in terms of institutions, human capital, infrastructure, market, and business sophistication parameters, as shown in Figure 4. Therefore, the benefits derived from the Community whose members are ranked among the world’s lowest performers must be evaluated by Somalia.

Customs Union and Common Market

Somalia might realize benefits in joining the Community in two areas: Common Market and Customs Union, as this will help Somalia anchor its trade and investment policy to the protocols of integrating its customs and market into the Community.

- The Customs Union entails a common external tariff, duty-free and quota-free movement of tradable goods within the EAC, and common safety measures for regulating the importation of goods from third parties.

- The Common Market is anchored in the protocol, which “grants the right of establishment, settlement, and residence; freedom of persons’ movement, provision of labor and services; non-discrimination and equal rights between Partner States’ citizens and intraregional migrants.”

Somalia’s Integration in Customs Union

Somalia can further increase its efforts to strengthen regional and international trade agreements. In recent years, Somalia has used more active commercial diplomacy, which reflects the country’s efforts to give cross-border trade an important role in the country’s development. This increased commitment to trade negotiations at the regional and global levels. At the regional level, Somalia reestablished the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) in 2018 and applied to join the East African Community. In 2020, the Somali government approved the country’s African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) membership, but its ratification awaits parliamentary approval. Enhanced harmonization of multiple customs regimes could support Somalia’s long-term ambitions to join the World Trade Organization (WTO).

While Somalia would like to trade with the EAC members, given the vital role of trade and investment policy for development, Somalia does not currently have an industrial scale production capacity in which it has a comparative advantage to trade with the EAC members. Currently, Somalia imports basic goods and has a trade deficit that is estimated to be around 65% of the GDP (4); this deficit could grow if prices for goods like fuel and wheat continue to rise as a result of the Ukraine-related crisis. Somalia’s natural wealth assets include land, rivers, forests, mineral assets, and marine resources. Improving human capital can equip Somalis with the skills needed to improve productivity and respond to the opportunities of the evolving private sector. All of these will help Somalia achieve trade opportunities with the EAC member; however, Somalis is not there yet.

Due to its strategic location near important international routes and ports, Somalia offers a number of advantages that can help diversify its export partners beyond the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations. Regional trade agreements such as EAC, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), and the African Continental Free Trade Area (ACFTA) provide significant export opportunities for Somali producers. Developing regional integration can be aided by advancing a national trade strategy supporting Somalia’s trade-related institutions, harmonizing customs and border management processes, and strengthening producers’ capacity to meet importers’ sanitary and phytosanitary requirements. As Somalia strengthens its processes for implementing a single tariff schedule and building trade institutions, there may be opportunities to better position itself in membership.

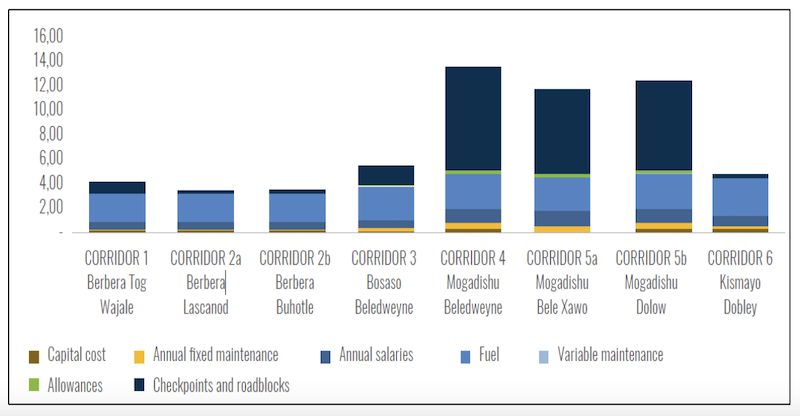

Due to Somalia’s domestic market fragmentation, as shown in Figure 5, trade and competitiveness are hampered, raising costs for producers and dampening competitiveness. Hence, Somalia must tackle its domestic regulatory framework, and addressing the drivers of fragmentation requires tackling illegal checkpoints through improved governance and high transportation costs. In addition, improved access to a dependable road network and power in strategic corridors could support trade within Somalia and in EAC.

Additionally, Somalia can work on modernizing and expanding its export industry. The types of goods Somalia can trade with EAC members should be diversified by strengthening value chains, for instance, in sectors like agriculture and fisheries. A stable security environment, supporting investments (such as in infrastructure and cold chains), and improved technical skills—including in the fields of food safety and animal health—will be necessary for upgrading value chains. In addition, public-private dialogue and information sharing with investors, such as by launching the trade information portal to support access to trade procedures, documents, and fee requirements, could be measures to support the business environment.

In the upcoming years, Somalia’s development and integration strategies will need to prioritize trade and foreign direct investment. In addition, however, the nation will need to give supply capacities and physical infrastructure immediate and concerted attention if export-led growth is to become a viable development option. Similar to the advice to previous aspirants of EAC membership, Somalia must guard against the risk of generating unrealistic expectations from its decision to seek EAC membership and engage in its trade- and investment-led integration process.

While the quality of institutional governance and the state of physical infrastructure are important factors for Somalia to realize any benefits in joining the Community; however, reviewing Somalia’s current developmental reality makes for sobering reading:

- Close to 70 percent of the population lives on less than US$1.90 a day. (5)

- Somalia is vulnerable to frequent climate-related and biological disasters. In addition, climate shocks impact livelihoods and exacerbate food insecurity risks, which trigger internal displacement.

- It is estimated that only 2,860 kilometers (km) of the 21,830 km of roads in the country are paved (13%)—and most are in poor condition.

- Health conditions are basic at best, with one of the highest infant mortalities rates in Africa and the lowest per capita number of medical professionals on the continent.

- Firms and households suffer from generally poor access to high-cost electricity.

- Despite its considerable agricultural potential, Somalia highly depends on food imports.

- A significant shortage of technocratic expertise impedes the capacity to design and

- implement indigenously decreed policy choices.

- The country suffers from over-dependence on remittances, and 70.2% of the government’s budget comes from international donors, which poses major governance and macroeconomic risks and challenges such dependence typically entails. (6)

Given the above facts, Somalia’s decision-makers must evaluate the case for EAC membership in light of many challenging issues. Somali policymakers need to be realistic about the likely time frame and how much regional integration improve Somalia’s development prospects. Additionally, what role can Somalia realistically assign to trade- and investment-led integration, which is the foundation of today’s negotiated regional integration initiatives? By rushing into EAC membership in a situation where resources are severely limited and there is insufficient capacity to supply regional markets, Somalia runs the risk of being the dumping ground of imports from EAC members. Finally, given the dearth of technocratic expertise, Somalia will probably continue to be an EAC rule-taker for some time; therefore, policymakers’ expertise in regional and global economic governance and trade diplomacy needs to start as soon as possible.

Somalia’s Integration in Common Market and Labor Mobility

Although Somalia has vast diaspora members in some EAC members, managing cross-border labor mobility is still a complex and delicate political challenge, particularly the severe domestic skill shortages and a weak labor export capacity characterized by Somalia due to years of conflict which caused brain drain. Somalia also needs to contend with what labor market effects, for both skilled and unskilled workers, would EAC membership likely generate. Moreover, 75 percent of Somalia’s population is under 30 and with limited employment opportunities. As shown in Figure 6, labor participation (37 and 58 percent for women and men, respectively) is low for Somalia, and cross-border labor mobility within EAC will likely lower it further.

Somalia’s Regional Integration

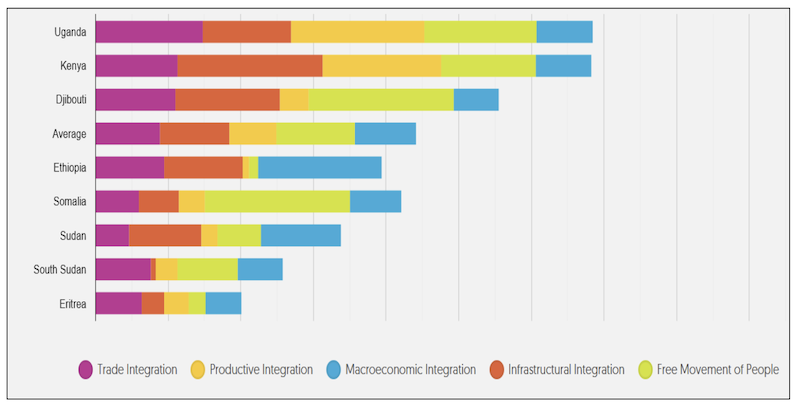

The 2019 Africa Regional Integration Index (ARII) evaluates the regional integration progress of countries belonging to the eight regional economic communities acknowledged by the African Union. ARII measures how each country performs against the other nations in its regional economic community, as well as the countries across Africa. (7)

Figure 7 shows how each country in IGAD performs on the five dimensions of regional integration. Given the low integration into IGAD, Somalia’s would need improvement in integrating into the EAC.

As shown in Chart 8, Somalia compares low to current members of EAC. Countries with shared borders are known to trade more efficiently, with lower transaction costs. Factors such as historical ties, policies, advantages, and topography are crucial in integration. The ARII (Africa Regional Integration Index) is a tool used to measure integration across five dimensions, providing policymakers with insights into successful policies and areas for improvement. Therefore, Somalia should assess how it can benefit from EAC membership, given its low level of integration.

Recommendations for Possible Integration Speed for Somalia

While Somalia is a fragile country and will likely be a rule-taker of the EAC, with the right reforms, Somalia’s development could be enhanced due to EAC integration. With the right reforms that the EAC wants Somalia to implement, a variable geometry integration will be prudent. (8) FGS’ special envoy and the technical experts working with him, should become familiar with the different applications of variable geometry that are used around the world and not rush into free trade and customs union integration which will not benefit Somalia.

Variable geometry integration is allowed in the EAC community. Somalia needs to integrate into the customs union and the common market gradually; however, EAC should first request that Somalia upgrade and build its national institutions. The FGS and FMS should strengthen tax policy, paying particular attention to the fiscal regimes for inland and customs revenues that can be harmonized to further the federal objective and eventually accession to EAC membership. Suggestive approaches for Somalia could be:

- Somali-tailored integration with a goal of closing the development, income, and capacity gaps. This method has been effective and has contributed to other countries’ transition to middle-income status and was a recommendation for South Sudan.

- Easing the labor movement to Somalia given the impact of Somalia’s low labor participation; therefore, differentiated treatment of labor mobility and longer transition periods for full labor mobility from current EAC members with greater skills and income gaps.

- EAC-monitored integration program for Somalia to prevent the negative impacts of cheap imports from the current EAC members.

Conclusion

Somalia is not ready for deep integration into the EAC Community. Still, after reforming its national institutions, a variable geometry of incremental approach to EAC membership could usher in new fast-tracked reforms for Somalia regarding financial regulations, healthcare modernization, and small industry development. Accession can be staged across various integration instruments or across various EAC Common Market freedoms for Somalia. In addition, Somalia can be given extended transition periods to conform with EAC regulatory requirements.

While EAC membership isn’t a magic bullet for Somalia, with the right reforms ushered in by the requirements of being a member, the benefits and costs of membership need to be weighed carefully and measured against the daunting domestic challenges facing Somalia. Some of Somalia’s domestic challenges are also common in other EAC partner states such as Burundi and South Sudan (e.g., political instability, the fragility of the economy, internal conflicts, weak regulatory frameworks, and institutions’ low diversification of their economies, etc.); however, they still are members and benefit from being in the EAC. Nonetheless, unlike Somalia these countries did not experience state collapse.

About the author: Abdighani Hirad is a financial risk professional with over 20 years of experience in financial compliance, evaluation, and monitoring in banking and financial institutions. He holds a BS in Economics and an MS in Statistics from George Mason University.

Endnotes:

- see author

- https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/April/weo-report?c=618,636,664,714,733,738,746,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,LP,&sy=2022&ey=2022&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1

- https://www.eac.int/press-releases/2711-eac-officially-launches-the-verification-mission-to-assess-somalia-s-readiness-to-join-the-community

- SOMALIA POLICY NOTES FOR THE NEW GOVERNMENT Unlocking Somalia’s Potential to Stabilize, Grow and Prosper June 2022, Macroeconomics, Trade, and Investment

- IMF Country Report No. 22/375, “2022 ARTICLE IV CONSULTATION AND FOURTH REVIEW UNDER THE EXTENDED CREDIT FACILITY—PRESS RELEASE; STAFF REPORT; AND STATEMENT BY THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR FOR SOMALIA,” December 2022.

- The Federal Republic of Somalia, “Appropriation Act of 2023, ACT No. 000021.”

- https://www.integrate-africa.org/about-the-index/why-measure-regional-integration-in-africa/

- Variable geometry is an approach in regional integration that allows member states to be flexible and choose differentiated speeds towards integration. It became the establishing principle for the integration Africa’s regional economic integration.

References:

The Federal Republic of Somalia, Appropriation Act of 2023, ACT No. 000021.

International Growth Center, “South Sudan’s EAC Accession Framing the Issues: Policy, 52001 | December 2012.

IMF Country Report No. 22/375, “2022 ARTICLE IV CONSULTATION AND FOURTH REVIEW UNDER THE EXTENDED CREDIT FACILITY—PRESS RELEASE; STAFF REPORT; AND STATEMENT BY THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR FOR SOMALIA,” December 2022.

Rwengabo, Sabastiano, 2015. ‘From Migration Regime to Regional Citizenry: Migration

and Identity Implications of the East African Common Market, Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review, 31 (2):35-61

WIPO (2021). Global Innovation Index 2021: Tracking Innovation through the COVID-19 Crisis. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization.

World Bank. 2022. Policy Notes for the New Government: Unlocking Somalia’s Potential to Stabilize, Grow and Prosper. © World Bank.

World Economic and Financial Surveys: World Economic Outlook Database https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/April/weo-report?c=618,636,664,714,733,738,746,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,LP,&sy=2022&ey=2022&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1

This is very timely and in depth analysis which makes the case for not rushing to EAC membership for Somalia. A country emerging from long and drawn out state collapse of which its institution are still struggling with lots of issues.

Good Observation.