Comparing Western And African Democracy: Challenges And Opportunities – Analysis

Continuous imposition of the Western model of democracy will only lead to Western frustration and African rejection, just like in the Middle East, Latin America and other parts of the World.

By Tendaishe Tlou*

Since African states began attaining independence and implementing reforms, democracy has been became a key recipe and threshold for assessing developments in Africa. Since the end of the Cold War, democracy has been deemed the most successful framework for achieving social and economic progress. The feasibility of democracy in Africa, however, has long been questioned by scholars such as Shivji, Mazrui among others, considering the realities, issues and factors on the ground. These include the colonial legacy, the lack of an influential middle class, the supposed incompatibility of Western democracy with African culture, power struggles, lingering cultures of corruption and the marginalisation of the masses. There are however other variables which suggest that democracy, if nurtured correctly, may thrive in Africa. The feasibility of democracy in Africa depends on a number of factors, internal and external, key to fostering democracy.

Whilst there is no one universally acclaimed definition of democracy, Pennock (1979) defines it as, “government by the people, where liberty, equality and fraternity are secured to the greatest possible degree and in which human capacities are developed to the utmost, by means including free and full debate of common problems, differences and interests”. In the same vein, Schmitter and Karl (1991) define democracy as a system of governance in which rulers are held accountable for their actions in the public realm by citizens, acting indirectly through the competition and cooperation of their elected representatives. It should, however, be noted that African democracy can not be the same as other democracies, as they are founded on their own tradition. Democracy therefore remains an ambiguous term, full of many pitfalls in trying to prescribe a universal standard and definition.

The colonial legacy is a major obstacle to democracy in Africa. No account of the transition from authoritarian to democratic rule can be satisfactory if it ignores the pervasive influence of the entire socio-political setting, including the impact of colonialism, as they both condition the form and content of contemporary politics in Africa. The current plurality of divided, weak and mostly poor states in Africa has a bearing on the dynamics of African life and struggles for democracy. During the colonial era, boundaries were arbitrarily drawn, often splitting-up community, families, ethnic groups and cultural units, thereby destroying and undermining many indigenous structures and institutions of authority. Ethnic populations that were traditionally enemies found themselves within the same artificial boundaries, and no efforts were made by the colonial masters to facilitate ethnic, tribal and religious tolerance, but instead they opted to use a divide-and-rule strategy.

African states from their inception were naturally weak and multi-ethnic, thus it is difficult to administer them in the fashion of Western democracy. International boundaries in Africa therefore tend to have a detrimental affect on the development of democratic states and of coherent, viable and integrated economies. The 2014 South Sudanese and Central African Republic massacres are a testament of ethnic intolerance that resulted from the merging of different ethnic groups, to the detriment of democracy and human rights. The recurrent genocides in Africa are a sign of state failure which can be traced back to colonialism. As long as there is a continuous disregard for indigenous structures as a result of colonialism, the feasibility of democracy in Africa will not just be waiting for a train in the wrong station, but also waiting for a train that will never arrive.

In addition, a culture of corruption and autocratic political leadership is another factor that is bound to derail the feasibility of democracy in Africa. According to Szeftel (1989), colonial education created a small African political elite with oligarchic tendencies. This class preferred to perpetuate its own ascendancy and privileged status after independence rather than to share power with other groups in society. The incumbent Algerian President Ben Ali and Bongo of Gabon, amongst others, are a few examples. They both enjoyed the colonial French education and, when they rose to power, monopolized their country’s oil reserves to safeguard their political power, using oil money to remove opposition. Colonial education played an important role in further jeopardizing the feasibility of democracy in Africa.It is against this background that one can argue that even France and Britain after their respective revolutions had to constantly retrogress into dictatorship and remain poised between political regression and economic decomposition. Democracy is not an event but a process; one that can only be inculcated over centuries.

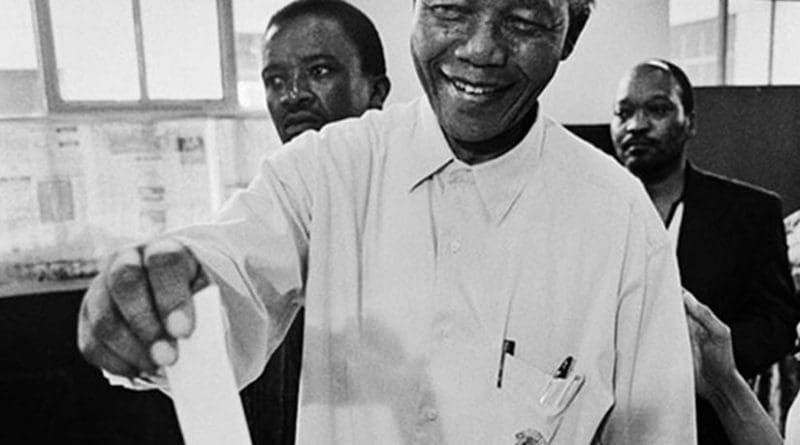

In Africa there remains a general lack of an influential business class. Ake (2000) observes that the flamboyant middle class which is relatively independent of the state tends to be a part of economic mismanagement and political authoritarianism. The business class in Africa is very small because of the rudimentary development of capitalism. The influence of the business class can be illustrated by how in South Africa it intervened in the process of democratization. Their initiatives managed to thwart Apartheid and facilitate the earlier contacts between the liberation movements and white elites. The business class, just like multi-lateral agencies, support the tenants of good governance, the rule of law, accountability and transparency. Ake (ibid.) maintains that the bourgeoisie has defined and re-defined democracy in an endless process of appropriating democratic legitimacy for political values; with interests finding practices that are in no way democratic.

However, the thrust of multilateral agencies support is for minimalist pluralism and electoral competition. Ake further highlights that some worry that democratisation may empower the masses to demand redistribution and incorporation into the state. Africa lacks such societies that can facilitate the democratisation process. Viewing democracy in Africa as feasible given its thin influential business class bases would be being myopic. A vibrant business class that is committed to facilitate democracy in a state is a necessity for democracy to thrive, hence its absence means otherwise. Chege (1994) has often invoked a powerful mantra on the political culture of democracy to wit, “No bourgeois, no democracy.”

On the flip-side, Friedman argues (1992) that democracy is a Western type of ideology which was founded to meet Western needs and wants, meaning that its applicability to the African context might prove to be unsuccessful. African democracy can not be the same as other democracies, because other democracies are founded on their own traditions. Hence, its applicability to Africa has been problematic since it is being imposed, rather than being left to mature on its own. Western democracy is mature, progressive and very comprehensive because democracy was given centuries to mature; learning from a plethora of mistakes that the authors and protagonists from the French revolution to the end of the Cold war have re-directed. In contrast, barely a few decades after attaining independence, African states are expected to be strong democracies without being given ample time to mature, making it more of an event than a process. This is neither fair, nor realistic.

Some African states after independence opted to choose Socialism as their ideology, but the demise of the Eastern bloc meant that they little choice but to embrace liberal democracy. Africa is therefore expected to be Western-oriented and hence democracy lacks an African integrated approach. This explains why Africa is stuck in between political regression and economic decomposition. Democracy in Africa can only be feasible if it is an ‘African grown democracy’, based on a Pan-Africanist ideology and fostered along cultural relativism, allowing democracy to be accepted and allowing it to mature rather than being imposed. Continuous imposition of the Western model of democracy will only lead to Western frustration and African rejection, just like in the Middle East, Latin America and other parts of the World.

Globalisation may have an effect in making democracy feasible in Africa. African countries through the various forms of media may come to appreciate the positive effects of democracy. In Western parts of the world, the masses are not marginalized in democratic movements and this may set precedence on which path to follow for African countries.

The feasibility of democracy in Africa is as complex as the continent’s challenges and prospects. Democracy itself is a foreign ideology, based on foreign culture and beliefs. Its applicability in Africa is therefore problematic. The colonial legacy itself created an imbalance within African society in social, cultural and economic terms, creating new challenges to democratization. Though the donor community may try to condition their aid, it has proven unsuccessful because of double standards and the tendency to look East for unconditional aid and investment. A Western type of democracy will therefore be blended with an African democracy or Africa will create its own democracy based on African culture and beliefs. Democracy as long as it is being imposed will never work. The USA took nearly 200 years for its democracy to mature, and such time must also be given to African countries. Democracy, like a revolution, must be left to ripen. As long as these unwritten principles are ignored, expecting the feasibility of democracy in Africa will not just be like waiting in the wrong station only, but also waiting for a train that will never arrive.

*Tendaishe Tlou is a freelance researcher and writer specialising in human rights, environmental security, peace and governance issues. He holds a BSc (Honours) Degree in Peace and Governance with Bindura University of Science Education and a Post-graduate Certificate in Applied Conflict Transformation. He works with various NGOs and Government Ministries in Zimbabwe and South Africa. However, these are his personal views; no authors, NGOs, Universities or any other Institution must be held accountable for the arguments in this article.