Nepal: Hunger, Enduring Food Crisis And The Right To Food – OpEd

Poverty has in recent years been hotly debated in the international human rights arena where it is recognised to be a ‘gross denial of human rights’. Its eradication is not only a development goal – it is a ‘central challenge for human rights in the 21st Century’. It bears repeating that today one billion people live in a style of luxury never before known in human history while at the same time one billion are destitute and forced to survive in inhuman living conditions. It is a well-established fact that poverty is a cause, as well as a consequence, of serious human rights violation. The World Food Summit (WFS) reaffirmed the right of everyone ‘to have access to safe and nutritious food, consistent with the right to adequate food and the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger’.

Poverty and hunger are, as it were, twin brothers. They are locked in a vicious circle, interconnected and invisible. They are a major source of conflict and violence, and they present a fundamental challenge to security and peace throughout the world. Millions of people are deprived of basic needs not through lack of resources but through a gross failure of governments and policy makers to take the issue seriously. Most importantly, there is a huge gap between theory and practice, saying and doing, and promising and providing. False promises dominate the issue.

A UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report states that in excess of 850 million people in the world suffer from hunger and that the Millennium target of halving that number by 2015 will not be met without stronger commitment at an accelerated pace. According to the report, failure will mean that over a billion people worldwide will be undernourished and most of them will be in developing countries. Of the billion, 642 million will be in Asia and Africa and only 15 million will be in the developed countries. The WFS Plan of Action, reaffirming that hunger and under nourishment are unacceptable, envisages an on-going effort to eradicate hunger in all countries, with an immediate view to meeting the Millennium target still by 2015.

The human right to food, as recognized under international law, aims to enable all human beings to feed themselves in dignity, either by producing their own food or by purchasing it. However, a question must be asked: why do so many millions of people go to bed every day hungry despite the right to sufficient food being guaranteed in constitutions and in laws as an entitlement for everybody living on this planet?

Inequitable distribution of food nationally and internationally has resulted in a huge disparity of consumption leading at times to civil strife and even to interstate war over natural resources. Statistics indicate that there is twice as much food as we need to feed the world, but ironically, as already stated, millions go hungry every day and their number is increasing. Many important questions must be asked today. Is the Millennium goal achievable without establishing a proper mechanism to redistribute productive and financial resources – internationally from richer to poorer countries, and nationally from richer to poorer classes especially those most vulnerable in society? Should poor people not enjoy their human right to food? Should they not have enough food to keep themselves alive and alert? Why are there so many disparities in food distribution at national and international level? Who is responsible?

In Nepal’s context, why do the right to food and the basic needs of their people not figure high on the agendas of politicians, political parties and even development agencies and NGOs? Why do some parts of the country always face food shortages? Where are the long-term agendas at governmental level? Should all people not receive subsidized food access? Despite the many political changes and revolutions, why are so many millions of ordinary people in Nepal still be unable to feed themselves properly? Many questions need to be asked of the government, and the politicians and policy makers must answer the people.

Food as a Human Right

The right to food is a fundamental human right directly related to the right to life. There can be no life without food. However, the right to food needs to be understood in the broader sense of being able to live with dignity. The human right to food originated at the very birth of UN system. It was recognized in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights as part of the right to an adequate standard of living. The right to adequate food then became enshrined in international human rights treaties such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966. It was recognized, too, in specific international instruments such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women 1979 and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2007.

The right to food has also been recognized in regional human rights instruments – such as the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child 1990, and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa 2003. The Voluntary Guidelines to Support the Progressive Realization of the Right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security adopted by the 127th Session of the FAO Council also provides, although as guidelines, a right to adequate food to people in a comprehensive manner. Many countries, moreover, have adopted the right to adequate food as a fundamental right in the supreme law of their land, the constitution.

As the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in its General Comment 12 explained: ‘the right to adequate food is realized when every man, woman and child, alone or in community with others, has physical and economic access at all times to adequate food or means for its procurement.’ Therefore, the right to be free from hunger and malnutrition and the right to access adequate food and to food security are fundamental human rights guaranteed by various national and international human rights legal instruments.

Dangerous nexus Between Politicians and the Land Mafia

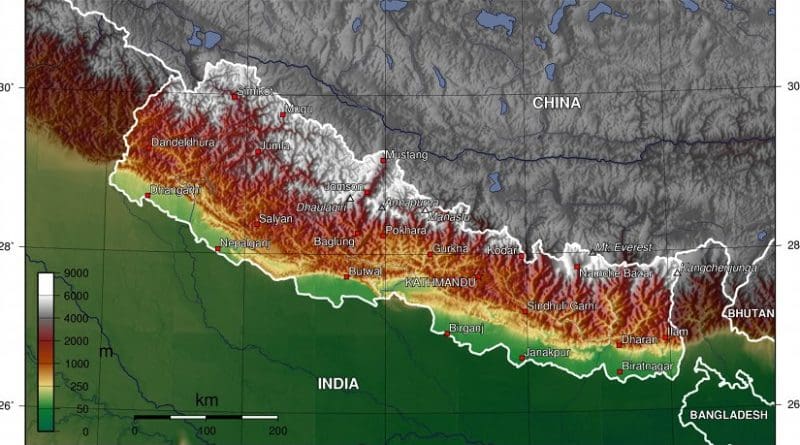

Statistics show that about six million people in Nepal suffer from hunger and poverty. Half of all children under the age of five suffer from malnutrition and stunting. Many parts of the Nepal face hunger from a shortage of food every year. The remote far west is permanently on the brink of a serious food crisis. Lacking meaningful irrigation, its rain-fed production can sustain the local population for little more than six months of the year. According to the Nepal Food Security Bulletin, Karnali and the Far Western Hill and Mountain region are the most vulnerable. Food deficiency has thus become the common phenomenon for years in many districts, and there is an urgent need to strengthen the food supply system to ensure adequate availability.

Nepal is party to almost all the major international human rights legal instruments that have been mentioned above. Moreover, the human right to food for its citizens is also provided for in the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2007. In addition to the preamble where there is a specific mention of the state’s obligation to fulfil the rights of its citizens, Article 18(3) provides for every citizen the right to food sovereignty, and Article 33(h) mentions that the state is obligated to ‘pursue a policy establishing the rights of all citizens to education, health and food sovereignty’.

Of the many principles of the right to adequate food, accessibility is one of the most important. It requires that economic and physical access to food is guaranteed, and that the food is also affordable. However, where are these things happening in their country today? The price of essential goods such as rice, vegetables, kerosene and petrol seem to rise every day and in every part of the country. The market appears to act as a monopoly. There is no proper market control and monitoring mechanism and the government and authorities concerned merely close their eyes. Further important questions can be asked: Do their politicians and political parties ever allow themselves to think about anything other than power and holding on to power? Why people’s basic needs are so much more easily accessed in the cities than in remoter parts of the country? Why is there so much disparity, and why do the elite representing only a few per cent of the population enjoy all the facilities and all the welfare schemes in their country? What went wrong?

The so-called land distribution scheme – a brainchild of over sixty years ago – has become the most politicised project in Nepal. The food and land distribution programmes now generate cheap slogans at every national election, and there is a dangerous nexus between politicians and the land mafia. Despite many promises politically and at policy level, land reformation and land redistribution to poor farmers have yet to be implemented. Dalits, indigenous people and other vulnerable groups are still landless and living in extreme poverty and malnourishment. Successive governments have failed to identify the real poor, the root causes of their poverty and who are the most vulnerable groups in our society. It is those who are near and dear to politicians and the political parties who have been the true beneficiaries of the social welfare schemes introduced by the state.

Millions of people in their country are therefore still deprived of their human right to food. As Amartya Sen once remarked: ‘The law stands between food availability and food entitlement.’ If they are to take seriously our duty towards the most marginalized and vulnerable, we must recognise the essential role of legal entitlement in ensuring that the poor have either the resources required to produce enough food for themselves or the purchasing power sufficient to procure food from the market. Oliver de Schutter, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to food, argues; ‘People are hungry not because there is too little food: they are hungry because they are marginalized economically and are powerless politically. Protecting the right to food through adequate institutions and monitoring mechanisms should therefore be a key part of any strategy against hunger.’

The right to food is the people’s fundamental right to be free from hunger. Only effective national strategies, plans and policies on the right to food can provide the impetus for national frameworks of law that can become the basis for long-term sustained visions for combating hunger. Nepal has so far failed to take responsibility in line with its commitment under various international agreements and covenants to fulfil the right to food. The country needs urgently to focus on development of the necessary infrastructure, on effective and equal distribution of resources, and on sound land and food policies. Only then shall they come close to assured availability of food for all.