Hidden Debt Hurts Economies: Better Disclosure Laws Can Help Ease The Pain – Analysis

By Alissa Ashcroft, Karla Vasquez and Rhoda Weeks-Brown

If efforts to address record global public debt are to leave no stone unturned, then weak disclosure laws warrant deep scrutiny. Hidden debt is borrowing for which a government is liable, but which is not disclosed to its citizens or to other creditors. And while this debt—by its nature—is often kept off the official government balance-sheet, it is very real, reaching $1 trillion globally by some estimates.

While these undisclosed obligations are not large when compared to global public debt topping $91 trillion, they pose a growing threat to low-income countries, already highly in debt with annual refinancing needs that have tripled in recent years. The problem is even more pressing amid higher interest rates and weaker economic growth. Accountability, too, is imperiled without accurate information about the extent of borrowing, which heightens the risk of corruption.

These potentially dire consequences can be avoided by strengthening domestic legal frameworks. Our new paper, The Legal Foundations of Public Debt Transparency: Aligning the Law with Good Practices, presents findings from a survey of 60 countries that examined vulnerabilities and loopholes in national laws that hinder transparency.

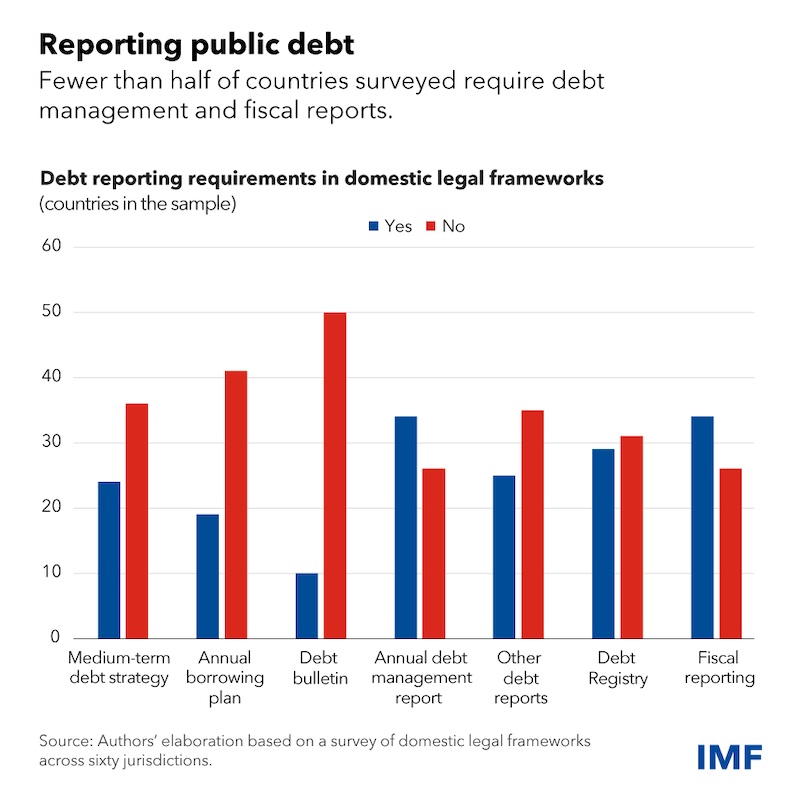

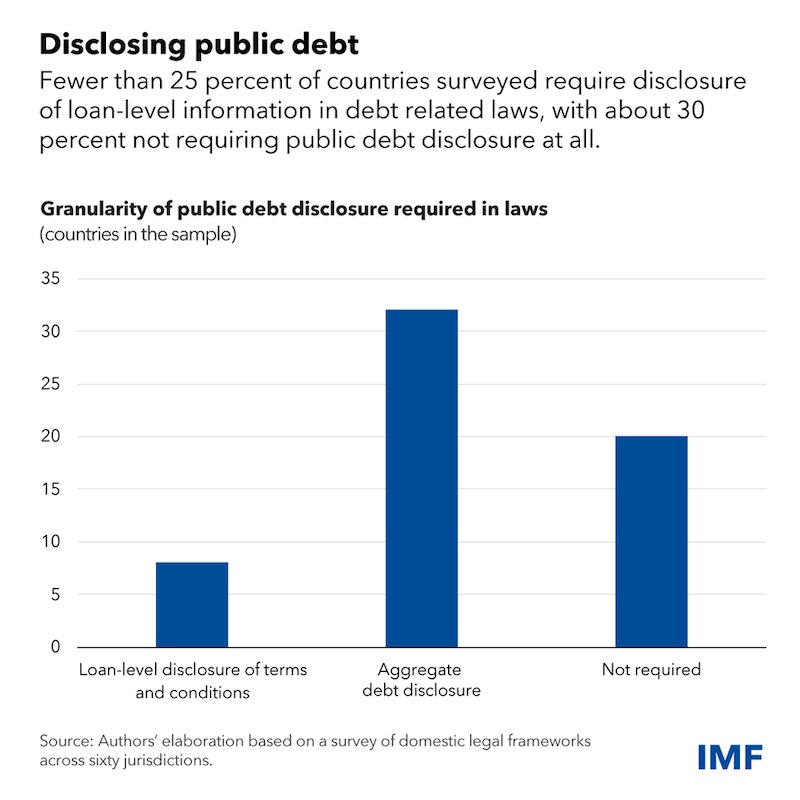

Building on a July 2023 paper, our new research shows that fewer than half the countries surveyed have laws that require debt management and fiscal reports, while less than a quarter require disclosure of loan-level information—key legal features for facilitating transparency. We also identify four noteworthy vulnerabilities in domestic laws that enable debt to be hidden: a narrow definition of public debt, inadequate legal requirements for disclosure, confidentiality clauses in public debt contracts, and ineffective oversight.

Definition

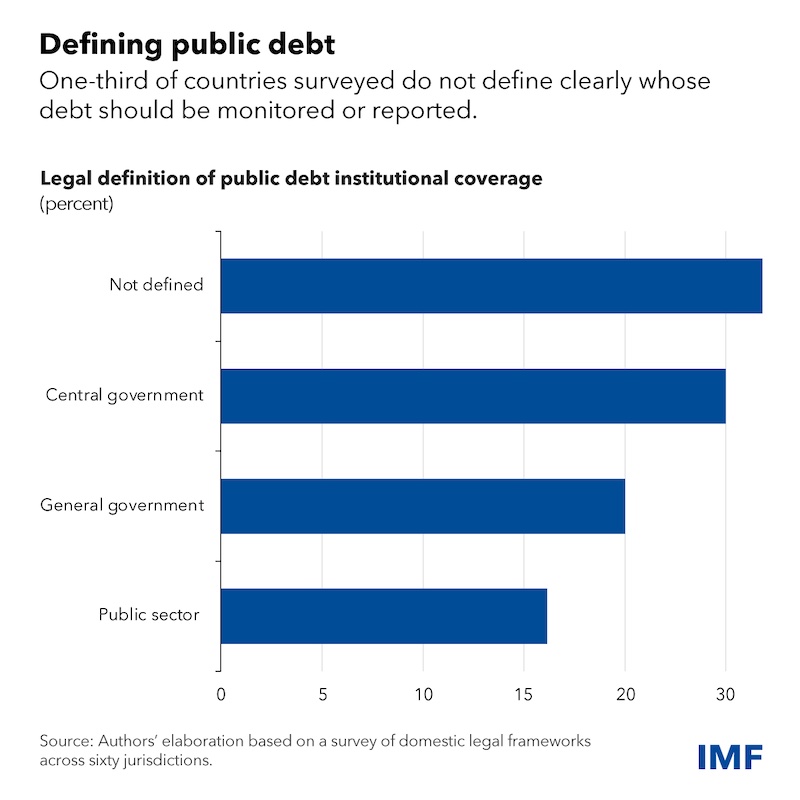

In many countries, a narrow definition of public debt, in one or in multiple laws, permits some forms of sovereign debt to escape oversight. We recommend that the definition of public debt be broad and comprehensive, meaning that it should capture arrears, derivatives and swaps, suppliers’ credit, and assumptions of guarantees as well as loans and securities. The definition should also cover extra budgetary funds, public trust funds (pension funds, for example), and special purpose vehicles.

A good example is found in Ecuador, which pursued legal reform in 2020 to ensure that short-term financing instruments—such as securities or treasury paper with terms of less than one year—were included in debt calculations and statistics. Other good examples include the legal definitions used in Ghana, Jamaica, Rwanda, Thailand and Vietnam, all of which encompass multiple types of debt instruments.

Disclosure

Second, across the globe, legal requirements for debt disclosure are inadequate. A strong legal basis is crucial to signal that there is a clear requirement to report debt data in a manner that is both timely and relevant for policy analysis, transparency and accountability. Strong reporting laws are found in in Benin, Kenya and Rwanda, which define both public debt reporting requirements and the timeframes for these reports.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality in public debt contracts directly hinders transparency. Across the globe, few laws regulate (and limit) the confidentiality of public debt, which hands policymakerswide discretion to label such contracts confidential for national security or other reasons. This is exacerbated by the fact that current debt-related international standards and guidelines provide limited guidance on how to tackle confidentiality issues.

We recommend that the law tightly define exceptions to disclosure and the scope of confidentiality agreements. Legislative oversight and other safeguard mechanisms such as administrative or judicial remedies should also be spelled out in the applicable legal provisions. Laws in Japan, Moldova and Poland are among the few that authorize legislative or parliamentary oversight of confidential information.

Oversight

The disclosure of public debt may also be inhibited where there is ineffective oversight governance by legislatures and supreme audit institutions (national government audit institutions), which are all important guarantors of accountability. Legislative bodies must be able to monitor and scrutinize public debt on behalf of the people, and they need to have staff able to read and grasp highly technical reports.

Several legislatures have a committee system—such as committees on the budget and public accounts—which allows for specialization among legislators. An example is in the United States, where the Treasury Secretary is required by law to send the annual public debt report not to Congress as a whole, but to two specific committees—House Ways and Means and Senate Finance. We also recommend that laws provide supreme audit institutions with the authority and the necessary powers to monitor and audit government debt and debt operations.

IMF role

Debt transparency not only benefits countries directly, but it is also essential for the work of the IMF. Hidden and otherwise opaque forms of debt make it more difficult for the Fund to fulfill its core mandate in a number of ways. For example, collateralized loans, novel and complex forms of financing, and confidentiality agreements make it difficult for the IMF to accurately assess a country’s debt and help bring its economy back on track.

Thus, the Fund works to bring the benefits of debt transparency to countries directly through technical assistance and also addresses the issue in our program engagements.

Well-designed laws make it harder to hide debt. But there are not enough of these laws on the books, despite their demonstrated benefits. Given the critical importance of getting transparency right, countries and their international partners must push for reforms to improve domestic legal frameworks, which in turn benefits both borrowers, legitimate creditors, and the system more broadly. Turning stones has never been more important.

— Kika Alex-Okoh contributed to this article.

About the authors:

- Ms. Alissa Ashcroft is a senior counsel in the Fiscal and Financial Law Division of the IMF’s Legal Department. Before joining the Fund, Ms. Ashcroft worked at the Congressional Budget Office in Washington DC where she served as an Assistant General Counsel and later as Acting General Counsel.

- Ms. Karla Vásquez Suarez is a senior counsel in the IMF’s Legal Department with more than fifteen years of experience in debt management, public finance and financial sector supervision. She has provided legal advice in Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and the MENA region.

- Rhoda Weeks-Brown is General Counsel and Director of the IMF’s Legal Department. She advises the IMF’s Executive Board, management, staff and country membership on all legal aspects of the IMF’s operations, including its lending, regulatory and advisory functions. Over her career at the IMF, she has led the Legal Department’s work on a wide range of significant policy and country matters. She has also lectured and written articles and many IMF Board papers on all aspects of the law of the IMF and co-taught a Tulane University seminar on that topic.

Source: This article was published at IMF Blog