India’s Blackout: A Case Of Rotten Infrastructure – Analysis

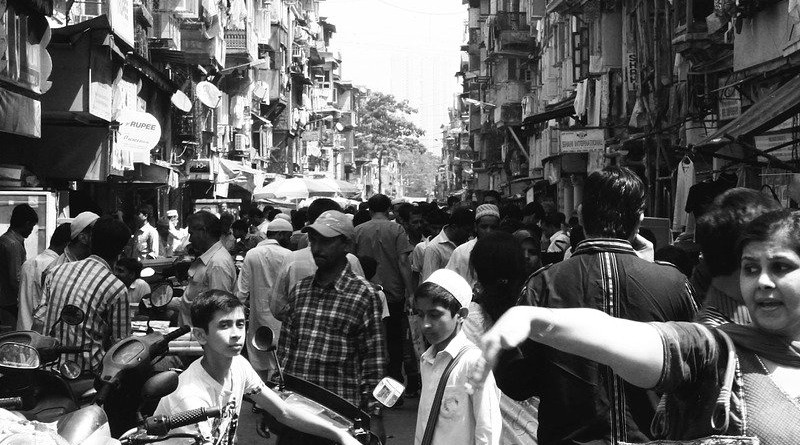

For an aspiring economic superpower, there can be few more chastening events than electricity cuts as massive as those that struck northern and eastern India this week. India suffered two massive power failures in as many days. More than 600 million people were affected, with disruptions not only in electricity, but in transport around the north of the country as well.

Infrastructure, from traffic lights to trains stopped working. Hospitals, sanitation plants and offices ground to a halt. Airports and factories had to rely on backup generators, often fuelled by truckloads of diesel. The first power grid collapse, on Monday affected seven northern Indian, home to more than 350 million people. Tuesday’s failure was larger, setting a world record for blackouts and disrupting activity on an even more massive scale than the day before. The blackouts come at an unfortunate time, coinciding with a worrying drought and sweltering summer temperatures. The impact on India’s economy goes far beyond lost output. The blackout will badly damage the country’s reputation, and highlights the rotten infrastructure that is hobbling its efforts to catch up with China.

A blame game began almost immediately as regional leaders, national politicians and officials tried to evade responsibility. Politicians shirk these tasks because they fear offending powerful lobbies, such as the farmers who receive subsidized electricity, while voters seem to manifest little appetite for reform. No party has a clear majority in parliament, and none was elected on a platform of change. The present Congress-led coalition government has few people with a record of or an instinct for reform, save perhaps the Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, who has now run out of zip. It relies on fickle regional parties to stay in power. The opposition is no better—and possibly worse. Fairly or unfairly, the ruling Congress party is likely to be damaged most.

The cause of the blackouts is murky—an overloading of the national network that links together regional grids is the most likely explanation. By most accounts engineers did a heroic job of patching things up. But the power industry, which must double its output roughly every decade if India is to grow fast, has long been a disaster waiting to happen. A pile of private capital has been attracted to build new power stations. But the rest of the supply chain is a mess.

A single point of blame is difficult to discern. However, there are a number of reasons why this could have happened and why it could happen again. Currently there is a drought, a weak monsoon season (20 per cent below average), and temperatures in northern India that have been soaring. As homes and office buildings turn up their air conditioners, and as farms increase their use of irrigation pumps, they draw more power from the system. At the same time, low rainfall also affects India’s sources of hydropower, delivering less juice into the system. But perhaps the most important reason is that with India’s rapid economic growth, the supply and distribution of power have simply not kept pace. Even if enough power were generated, the transmission system could not effectively distribute it. The power generation and distribution systems are in dire need of expansion and investment in order to keep up with rapid development—none of which is happening, for a varieties of political and environmental reasons. India’s state governments also provide free electricity to a large swath of the population, adding to demand and leaving the state and power companies to pick up the bill—incurring yawning deficits—while creating no extra supply. Nearly 30 per cent of power also is stolen.

There has been much discussion of potential solutions to the recurring blackouts throughout India. They vary from reforming the grid to enforcing strict penalties for “overdrawing” to encouraging more off-grid and renewable solutions to expanding coal mining. India’s latest five-year plan calls for a 50 trillion rupee (approximately US$1 trillion) investment in the infrastructure sector, with 50 per cent of that coming from the private sector. This includes a plan to bring $400 billion in investment into the power industry to modernize India’s electrical grid.

Average citizens take blackouts in relative stride, experiencing outages of 2 to 12 hours on a daily basis depending on where they live. Many homes and office buildings have backup diesel generators and are largely unaffected. Approximately 300 million citizens do not have access to power to start with. Of those affected, it is safe to say that the hardest hit are small and medium-sized businesses, which often cannot afford backup generators and so cannot operate during the outages. These outages has to be seen as a sign of a much larger issue—that India does not have the capacity to keep up with its growth—and this is a major source of concern as India’s appeal as an investment destination has recently taken a hit.

The Indian government has set up a three-member panel to get to the bottom of the blackouts and report back in two weeks. That’s a start, but without addressing deep-rooted political problems, ranging from land acquisition to unaffordable state subsidies, it will be difficult to effectively address India’s current power and infrastructure insufficiencies. Effective administration in a few of India’s states can serve as an example for others, especially when it comes to availability and consistency of electricity; it is not necessary to look outside for answers, as other states can already serve as models. Also, much has been reported about the fear that power outages will keep foreign investment away from India. But this is mostly unfounded, as private industry has generators for backup and some companies have built their own private power plants. Other infrastructure issues like railways, ports, and cold-chain technology pose more of an impediment.

India’s governments (national and state) must work seriously toward investing in their power generation and transmission capacities.

The solution is to cut graft, tackle vested interests and allow markets to work better. The coal monopoly needs to be broken up and local distribution firms privatized. Yet despite the looming crisis, for a decade the government has shirked doing what is clearly necessary, just as it has failed to implement key tax reforms, cut public borrowing or opens the retail sector to competition. It has allowed corruption and red tape to damage other vital industries, such as telecoms.

The government’s reaction to the power cuts has been depressingly in line with its more recent performance. During the blackouts it enacted a cabinet reshuffle, and the power minister was promoted to a more senior post. Yet there are some grounds with the hope that things may change. The very scale of the power cuts may remind voters that bad economic policies are not just abstract notions, but hurt people’s lives by making jobs scarcer, roads more congested, and food and phones more expensive. And that in turn may remind politicians of the dangers of ignoring the economy.

India’s great blackout is a consequence of rotten governance. Voters need to understand that, and deliver the country’s political class a different kind of electric shock. No doubt, from August the grid was sparking back to life. But the blackouts will have a lasting effect. Beyond the poverty of politics in India, three problems loom large: the narrow fault that caused the blackouts; the wider crisis in India’s power sector; and the shoddy state of the country’s infrastructure, from roads to power stations, which is a brake on economic development.

On the first, the technical glitch, the best explanation is that some states used more than their quota of power from the national transmission network that links up India’s five regional grids. The extra demand may have reflected a disappointing monsoon that forced farmers to pump more water for their fields. In any case, it overburdened the system, causing a cascade of failures. To cut the burden, power plants were shut down, some automatically.

It could have happened anywhere in the world due to human error and the greediness of some states, not shoddy equipment. Furthermore, despite a recent surge in investment, the transmission network is not up to scratch. The transmission network is not the only vulnerable part of the power supply chain, which is one giant bottleneck. Frequent minor blackouts are common. As a result most large firms, and even India’s airports, have backup generators or their own mini-power stations. The pressure will only grow. Demand is expected roughly to double over the next decade as manufacturing output expands and more Indians buy televisions, computers and fridges. That prospect has led to a boom in private investment in new power stations—which should be one of India’s big success stories.

But the rest of the supply chain is rotten. Not enough coal is being dug up by the state monopolist, Coal India. Electricity still needs to be shifted around the country, from coal-rich states in the east to the industrial west —yet the transmission system is rickety, as the blackouts showed. Finally, power must be delivered down the “last mile” to homes and businesses. Most local distribution firms are state-owned and all but bankrupt, as politicians insist that tariffs stay low and that big swathes of the population, including farmers, get free power. Many Indians get away with simply stealing it.

Private-sector power plant firms are being squeezed by fuel shortages and by end-customers that are often financial zombies. As a result, power-generating firm/industry starts cutting back on long-term investment in new plants. Banks also face bad debts from projects that are no longer viable, so troubles in the power-supply business spread to the rest of the economy.

Despite these problems, the government has merely applied sticking plasters and tried to knock heads together. It has ducked fundamental reform, which would probably involve breaking up Coal India, privatizing local distribution companies and installing new regulators with teeth. Its reluctance to shake up the power market is coming back to haunt it.

It is true that other parts of India’s infrastructure are in somewhat better shape. A vast effort has been made over the past decade to stiffen India’s economic backbone, and the results can be seen from a new airport in Delhi and a metro system in Bangalore to the availability of a mobile-phone signal almost everywhere. Yet without electricity, the life blood of an economy, some of these things will not work. And there is no question that at least half a decade of government complacency and incompetence is beginning to hurt the private investment that India must rely on. Plenty of trophy projects, which involve experimental public-private partnerships are not making money and face uncertain rules. India needs to invest a tenth of its GDP in infrastructure every year to sustain growth of 8 per cent or more. Investment has probably slipped well below that.