Why Climate Alarmism Hurts Us All – OpEd

In July of this year, one of Lauren Jeffrey’s science teachers made an off-hand comment about how climate change could be apocalyptic. Jeffrey is 17 years old and attends high school in Milton Keynes, a city of 230,000 people about 50 miles northwest of London.

“I did research on it and spent two months feeling quite anxious,” she told me. “I would hear young people around me talk about it and they were convinced that the world was going to end and they were going to die.”

In September, British psychologists warned of the impact on children of apocalyptic discussions of climate change. “There is no doubt in my mind that they are being emotionally impacted,” one expert said.

“I found a lot of blogs and videos talking about how we’re going extinct at various dates, 2030, 2035, from societal collapse,” said Jeffrey. “That’s when I started to get quite nervous and worried. I tried to forget it at first but it kept popping up in my mind.”

In October, British television aired repeated claims by spokespersons for Extinction Rebellion that “billions would die” from climate change.

“In October I was hearing people my age saying things I found quite disturbing,” says Jeffrey. “‘It’s too late to do anything. ‘There is no future anymore.’ ‘We’re basically doomed.’ ‘We should give up.'”

Leading celebrities including Benedict Cumberbatch, Stephen Fry, Emma Thompson, Olivia Colman, Ellie Goulding, Tom Yorke, Bob Geldof, and a Spice Girl have all promoted Extinction Rebellion in recent weeks.

“I did research and found there was a lot of misinformation on the denial side of things and also on the doomsayer side of things,” said Jeffrey.

Since early October, Jeffrey has posted seven videos to YouTube, and joined Twitter. I discovered her videos after googling “extinction rebellion millions will die.”

“As important as your cause is,” said Jeffrey in one of the videos, an open letter to Extinction Rebellion, “your persistent exaggeration of the facts has the potential to do more harm than good to the scientific credibility of your cause as well as to the psychological well-being of my generation.”

Why There’s No Apocalypse in Science

In my last column, I pointed out that there is no scientific basis for claims that climate change will be apocalyptic, and argued that environmental journalists and climate activists alike have an obligation to separate fact from fiction.

If you haven’t read that column yet, I hope you do so before continuing.

Part of what inspired me to write that column is that I am concerned by the rising eco-anxiety among young people. My daughter is 14 years old. While she herself is not scared, in part because I have explained the science to her, she told me many of her peers are.

In 2017, the American Psychological Association diagnosed rising eco-anxiety and called it “a chronic fear of environmental doom.” Studies from around the world document growing anxiety and depression, particularly among children, about climate change.

“One of my friends was convinced there would be a collapse of society in 2030 and ‘near term human extinction’ in 2050,” said Jeffrey. “She concluded that we’ve got ten years left to live.”

For the last two years, British and international news media have published and broadcast claims by Extinction Rebellion founders and spokespersons that “billions will die” and “life on Earth is dying” from climate change, often without saying explicitly in the stories that such claims are not scientific.

I wanted to know what Extinction Rebellion was basing its apocalyptic claims upon, and so I interviewed its main spokesperson, Sarah Lunnon.

“It’s not Sarah Lunnon saying billions of people are going to die,” Lunnon told me. “The science is saying we’re headed to 4 degrees warming and people like Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall Center and Johan Rockström from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research are saying that such a temperature rise is incompatible with civilized life. Johan said he could not see how an Earth at 4 degrees (Celsius) warming could support a billion or even half-billion people.”

Lunnon is referring to an article published in The Guardian last May, which quoted Rockström saying, “It’s difficult to see how we could accommodate a billion people or even half of that” at a 4-degree temperature rise.

I pointed out that there is nothing in any of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports that has ever suggested anything like what she is attributing to Anderson and Rockström. Why should we rely on the speculations of two scientists over the IPCC?

“It’s not about choosing science,” said Lunnon, “it’s about looking at the risk we’re facing. And the IPCC report lays out the different trajectories from where we are and some of them are very very bleak.”

To get to the bottom of the “billions will die” claim, I interviewed Rockström by phone.

He told me that the Guardian reporter had misunderstood him and that he had said, “It’s difficult to see how we could accommodate eight billion people or even half of that,” not “a billion people.”

Rockström said he had not seen the misquote until I emailed him, and that he had requested a correction, which the Guardian made last Thursday. Even so, Rockström stood by his prediction of four billion deaths.

“I don’t see scientific evidence that a four-degree celsius planet can host eight billion people,” he said. “This is, in my assessment, a scientifically justified statement, as we don’t have evidence that we can provide freshwater or feed or shelter today’s world population of eight billion in a four-degree world. My expert judgment, furthermore, is that it may even be doubtful if we can host half of that, meaning four billion.”

Rockström said half of Earth’s surface would be uninhabitable, people would be forced to migrate to the poles, and other shocks and stressors would result from heatwaves and rising sea levels.

But is there IPCC science showing that food production would actually decline? “As far as I know they don’t say anything about the potential population that can be fed at different degrees of warming,” he said.

Has anyone, I asked, done a study of what happens to food production at 4 degrees warming? “That’s a good question,” said Rockström, who is an agronomist. “I must admit I have not seen a study. It seems like such an interesting and important question.”

In fact, scientists, including two of Rockström’s colleagues at the Potsdam Institute, recently modeled food production.

Their main finding was that climate change policies are more likely to hurt food production and worsen rural poverty than climate change itself, even at 4 to 5 degrees warming.

The “climate policies” the authors refer to are ones that would make energy more expensive and result in more bioenergy (the burning of biofuels and biomass), which would increase land scarcity and drive up food costs.

“Although it is projected that the negative effects of climate change will increase over time, our conclusions that the effect on agriculture of mitigation is stronger would probably hold even if moving the time horizon to 2080 and considering the strong climate change scenario RCP8.5,” the scenario that IPCC says would lead to a 3 to 5 degree warming.

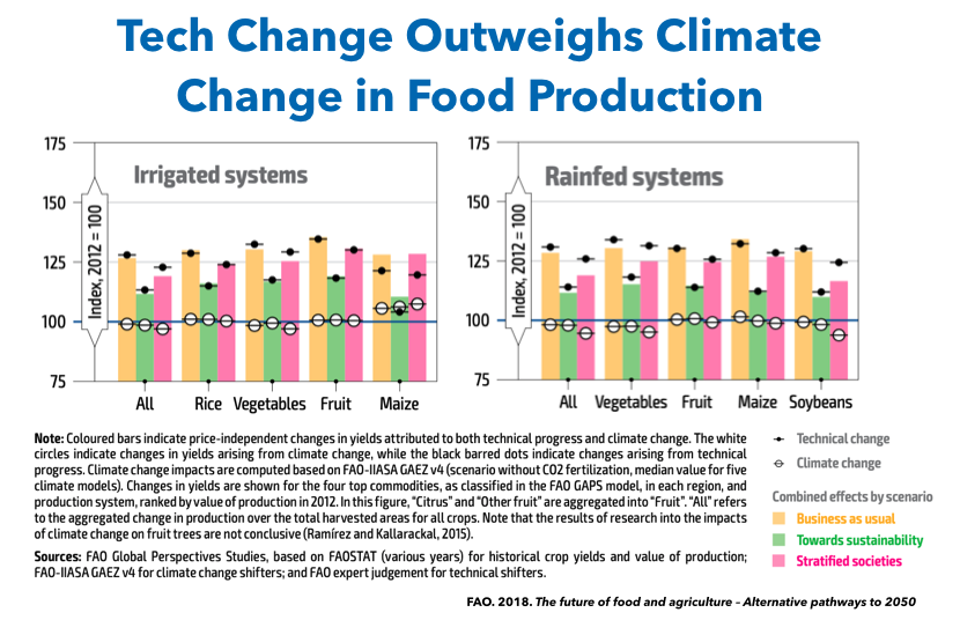

Similarly, UN Food and Agriculture concludes that food production will rise 30 percent by 2050 unless “sustainable practices” are adopted in which case it would rise just 10 to 20 percent. Technological change significantly outweighs climate change in every single one of FAOs scenarios.

What about the claim IPCC author Michael Oppenheimer made to The Atlantic that a 2 foot 9 inches sea level rise would be “an unmanageable problem”?

“There was a mistake in the article by the reporter,” Oppenheimer told me. “He had 2 feet nine inches. The actual number, which is based on the sea-level rise amount in [IPCC Representative Concentration Pathway] 8.5 for its [Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate] report is 1.1 meters which is 3 feet 7 inches.”

But what exactly would be “unmanageable” about a 3 feet 7-inch sea-level rise between now and 2100? I asked.

Oppenheimer pointed to failures by the cities of New Orleans and New York to prepare for big hurricanes like Katrina in 2005 and Sandy in 2012.

But couldn’t places like Bangladesh simply do what the Netherlands did? One-third of the Netherlands is below sea level, and some parts of it are seven meters under sea level.

“The Netherlands spent a lot of time not improving its dikes due to two World Wars and a depression,” said Oppenheimer, “and didn’t start modernizing them until the disastrous 1953 flood.”

The 1953 flood killed over 2,500 people and motivated the Netherlands to rebuild its dikes and canals.

“Most of humanity will not be able to avail itself of that luxury,” said Oppenheimer. “So in most places, they will accommodate flooding by raising structures or floodable structures. Or you retreat.”

But is retreating from communities built along the coast really “unmanageable”? I asked.

“People moved out of New York after Hurricane Sandy,” acknowledged Oppenheimer. “I wouldn’t call that unmanageable. Temporarily unmanageable. Meaning we wouldn’t be able to maintain societal function around the world if sea level rise approaches those close to 4 feet. Bangladeshis might be leaving the coast and trying to get into India.”

But millions of small farmers, like the ones on Bangladeshi’s low-lying coasts, move to cities every year, I pointed out. Doesn’t the word “unmanageable” suggested a permanent societal breakdown.

“When you have people making decisions they are essentially compelled to make,” he said, “that’s what I’m referring to as ‘an unmanageable situation.’ The kind of situation that leads to economic disruption, disruption of livelihoods, disruption of your ability to control your destiny, and people dying. You can argue that they get manageable. You recover from disasters. But the people who died didn’t recover.”

In other words, the problems from sea level rise that Oppenheimer is calling “unmanageable” are situations like the ones that already occur, such as in the days following Hurricane Katrina, where societies become temporarily difficult to manage. (Katrina killed over 1,800).

We should be concerned about the impact of climate change on vulnerable populations, without question. There is nothing automatic about adaptation.

But it’s clear that there is simply no science that supports claims that rising sea levels threaten civilization much less the apocalypse.

Tipping Points?

After I wrote my last column, several people asked me about climate “tipping points,” such as the collapse of ice sheets from Antarctica and Greenland, the escape of methane gas from melting tundra, the slowing of circulation in the Atlantic ocean, and the drying out and burning up of the Amazon.

In response I pointed out that nowhere does IPCC predict any of those things would be catastrophic to human civilization much less apocalyptic.

If the Greenland ice sheet were to completely disintegrate, sea levels would rise by seven meters, but over a 1,000-year period. Even if temperatures rose 6° Celsius, the Greenland ice sheet would lose just 10 percent of its volume over 400 to 500 years.

The Nobel-winning economist, William Nordhaus, calculates that the total loss of the Greenland ice sheet would increase the optimal cost of carbon by just 5 percent.

As for the Amazon, the IPCC says “the likelihood of a climate-driven forest dieback by 2100 is lower than previously thought.”

In my last two columns, I discussed how non-climate factors outweigh climate change when it comes to fires around the world. The same is true for the Amazon.

“There is now medium confidence,” IPCC writes, that climate change alone will not drive large-scale forest loss by 2100, although shifts to drier forest types are predicted in the eastern Amazon.”

What will really matter is how much deforestation, fire, and other changes to landscapes there are, just like in California and Australia.

As for the circulation in the Atlantic ocean, the IPCC notes, “There is only limited evidence linking the current anomalously weak state of [the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation] AMOC to anthropogenic warming.”

While AMOC may likely weaken 11 to 34%, says IPCC “it is very unlikely that the MOC will undergo an abrupt transition or collapse in the 21st Century.”

In her new book, student climate activist Greta Thunberg warns of “unforeseen tipping points and feedback loops, like the extremely powerful methane gas escaping from rapidly thawing Arctic permafrost.”

But if methane gas escaping the permafrost were “unforeseen,” then Thunberg wouldn’t have forseen it.

In reality, climate scientists closely monitor the release of gases from the permafrost and take the additional warming from them into account in estimating temperature rises.

Last week, a group of scientists including Rockström argued in an opinion “Comment” at the journal Nature that “evidence is mounting” that the loss of the Amazon rainforest and West Antarctic ice sheet “could be more likely than was thought.”

What they described, however, would take place over hundreds and perhaps thousands of years. At no point do they predict “billions will die.”

Last week, when I interviewed the lead author of the Nature Comment, Professor Timothy Lenton of the University of Exeter, I asked him about a verb tense I found curious.

Lenton notes that the West Antarctic ice sheet “might have passed a tipping point” but goes on to say “when this sector collapses, it could destabilize the rest of the West Antarctic ice sheet like toppling dominoes — leading to about 3 metres of sea-level rise on a timescale of centuries to millennia.”

“When you say ‘when,'” I asked, “does that mean it’s an inevitability that it will collapse?”

“Well, we can’t rule out that it’s on the way out,” he said. “Any glaciologist specialist will tell you that we really want more data. Because it’s not trivial to monitor what’s going on in West Antarctica.”

“So the right word in your view is ‘when‘ not ‘if‘?” I asked.

“We can’t be absolutely sure,” Lenton said, “but if it is, it will have knock-on effects. With the limited data, it’s hard to rule out that it’s already collapsing.”

I wasn’t the only person who felt confused by the multiple “ifs” and “coulds” in the commentary. “The paper has a strange array of rising risks lumped as ‘tipping points,'” noted Columbia University Earth Institute’s Andy Revkin.

Justin Ritchie, a researcher at the University of British Columbia, highlighted 11 conditional statements in the four paragraphs summarizing the complicated causality for a “global cascade” of tipping points.

“I might be the only one,” writes Ritchie, “but after reading it I’m actually less convinced about imminent climate tipping points. One example: if it takes 11 ‘if’ statements to support an opinion, then it’s time to revisit the opinion’s substance.” (The word “could” is used 26 times.)

I asked Lenton if he agreed with the IPCC that “the likelihood of a climate-driven [Amazon] forest dieback by 2100 is lower than previously thought.”

“To be honest, the problem is a majority of the climate models predicted the Amazon getting wetter,” Lenton said, “but the observations are showing a drying trend, particularly in the key seasons.”

Most everyone agrees that the risks of climate change, including from tipping points, are significantly higher at four degrees above pre-industrial levels than they are at two degrees.

The good news is that the world may already be headed to temperatures closer to two degrees than four. A new report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts carbon emissions in 2040 as lower than in almost all of the IPCC scenarios.

“The global energy system today, as modeled by IEA, is tracking much closer to 2˚ of warming this century than previously thought,” notes Ritchie, due to lower use of coal.

Does that mean there is nothing to worry about? Of course not.

We should reduce the risk of climate change, including from tipping points, by moving from dirtier to cleaner fuel and helping finance the water, electrical, and farming infrastructure that poor nations need to become less vulnerable.

I was surprised to be asked whether some amount of exaggeration about climate change wasn’t necessary to grab people’s attention. My response was, “Not if journalists and scientists hope for any trust with the public.”

I asked Jeffrey how she would answer such a question.

“Raising awareness of an issue is important,” she said, “but there’s a difference between raising awareness and telling children younger than myself that they might not grow up. Climate fear-mongering has become very child-aimed. I see a lot of mental health issues and fatalism.”

Climate Scientists Speak Out

The good news is that mainstream climate scientists are starting to push back against the fear-mongering.

Jeffrey said she got some of her information from scientists writing for a web site called Climate Feedback, which debunked Extinction Rebellion’s pseudoscientific claims last August.

Others are using social media to speak out.

“Rupert, I am shocked by this talk,” tweeted Kings College climate scientist Tamsin Edwards last October at an Extinction Rebellion activist named Rupert Read. “Please stop telling children they may not grow up due to climate change.”

The video was of a July talk given to school children as young as 10 years old by Read, who began by climbing on top of a desk at the front of a large classroom at University College London.

“People sometimes ask you, ‘What are you going to be when you grow up?'” said Read. “But the question has to be, ‘What are you going to do if you grow up.'”

Dr. Jo House, a Bristol University climate scientist, tweeted at Read, “you spoke at our Net Zero conference in Oxford, you disagreed with the scientists while you made up untrue stuff, and said it was ok that [Extinction Rebellion] XR ‘stretched the truth’.”

On the same thread, a young man replied, “Thank you for speaking out against this. I am a young person and one of Read’s talks last year made my mental health spiral and I almost made some awful life decisions.”

Rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide among teenagers are at their highest levels in two decades in Britain and the United States.

At least some young people have decided to talk back to the climate alarmists.

“Adults tell young people the end of the world is coming and then have the nerve to ask, ‘Why is every teenager so depressed these days? Why does everyone have anxiety? Oh, it must be those terrible phones!’

“No — it’s you!” said Lauren Jeffrey. “It’s you people going around scaring the hell out of them with unscientific rubbish!”

The young man on Tasmin’s Twitter thread agreed. “Doomerism is honestly just about as dangerous as delay for the climate movement at the moment.”

Jeffrey hopes to be the first in her family to go to university next year. She has long enjoyed reading books about biology and says she may major in environmental studies.

“I’m not saying we shouldn’t talk to kids about climate change,” she says. “I’m saying we should take better care of our ecosystems and the world. What kids don’t need is people telling them they’re going to be dead in a few years’ time.”

This whole article reads like someone complaining about the noise and disturbance caused by fire engines and firefighters when his whole city is on fire.