Two Vital Buffers Against Climate Change Are Just Offshore

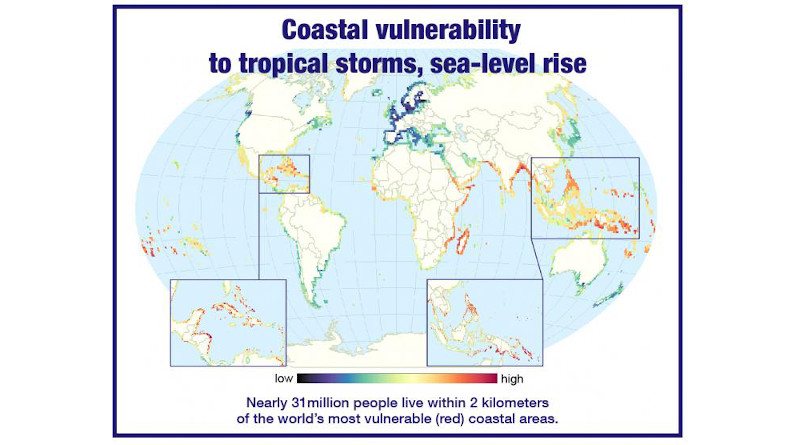

A new study finds that about 31 million people worldwide live in coastal regions that are “highly vulnerable” to future tropical storms and sea-level rise driven by climate change. But in some of those regions, powerful defenses are located just offshore.

Of those 31 million people, about 8.5 million directly benefit from the severe weather-protection of mangroves and coral reefs, key buffers that could help cushion the blow against future tropical storms and rising waters, according to the study published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE.

Because the two “natural infrastructures” absorb wave energy, reduce wave heights and provide a host of other environmental benefits, the study findings underscore the need for worldwide conservation and restoration of these natural resources. A particular focus, the authors said, should be placed on the most vulnerable regions, which lack available resources for more expensive protective measures, such as construction of levees or sea walls.

“Simply put, it’s much cheaper to conserve a mangrove than to build a sea wall,” said Northern Illinois University scientist Holly Jones, the study’s lead author.

A 100-meter-wide coastal strip of mangroves can reduce wave heights by as much as two-thirds, previous research has shown. Coral reefs meanwhile buffer wave energy by up to 97% in some contexts, significantly reducing erosion and cutting flood-damage costs in half annually.

“Coral reefs and mangroves serve as cost-efficient buffers against the adverse impacts of climate change, and they already play important roles in protecting human lives and livelihoods, while providing a multitude of biodiversity benefits,” said Jones, who holds a joint appointment at NIU in biological sciences and environmental studies.

Her co-authors on the research are Barry Nickel and Erika Zavaleta of the University of California, Santa Cruz; Tanja Srebotnjak of Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, California; and Will Turner, Mariano Gonzalez-Roglich and David G. Hole of Conservation International in Arlington, Virginia.

The ‘most vulnerable’

The study aimed to identify highly vulnerable coastal regions that would benefit most from “ecosystem-based adaptation,” or using conservation, restoration and sustainable management of existing ecosystems to address climate impacts.

Regions meeting study criteria for “highly vulnerable” were within two miles of coastline and scored in the top 10th percentile of the authors’ vulnerability index for being highly exposed to the effects of tropical storms and/or sea-level rise, dense in population and low in “adaptive capacity.” The authors developed the adaptive-capacity measure to take into account economic data, education levels and other factors that play into a region’s ability to adjust to climate variability.

The authors found that 30.9 million people globally live in regions that are most vulnerable to tropical storms and projected sea-level rise.

“Our estimate is very conservative,” Jones said. “This population lives in regions in the top 10th percentile for vulnerability. If we apply our model to coastal regions that scored in the top half for vulnerability, the population soars to over 700 million people.”

Highly vulnerable, coastal regions that would benefit the most from the conservation of mangroves and coral reefs span across Central America, the Caribbean, Eastern Africa, Southeast Asia and the South Pacific region. And yet only 38% of mangroves and 11% of coral reefs located along the most vulnerable coastlines are protected, according to the study.

“Protection of mangroves and coral reefs is critical,” said Will Turner, study co-author and senior vice president of global strategies at Conservation International. “They have the potential to save lives, store carbon and support fisheries; the co-benefits they provide are great. At Conservation International, we’re working with local communities, carbon finance, governments and the insurance industry to ensure that generations will benefit from the protection and restoration of these ecosystems.”

The authors noted that many of the world’s coastal zones already bear the brunt of extreme weather. Events such as Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas and hurricanes Maria, Harvey and Irma in the United States and the Caribbean claimed thousands of lives and generated financial costs running into hundreds of billions of dollars.

Additionally, past research indicates that the loss of lives and assets in coastal zones is likely to increase significantly as a result of demographic and socio-economic trends alone, leading to a doubling or more of hurricane damages by 2100.

U.S. could benefit, too

Coastlines in Florida and the U.S. island territories of Puerto Rico and Guam also stand to benefit from mangrove and coral reef conservation and restoration.

Globally, the densest populations receiving adaptation benefits (people protected per hectare) from mangroves are in India, the United States and Ghana, the study found. The greatest amount of people protected per hectare of coral reefs are in South Africa, Singapore, China and the United States.

More than a billion coastal dwellers worldwide face some degree of vulnerability to climate change. While most coastal regions are outside of tropical zones and aren’t buffered by mangroves or coral reefs, other ecosystems such as wetlands, estuaries and seagrasses provide protective benefits, Jones said.

“The United States is a wealthy country and has more ability to adapt than other countries, but it still could see significant benefits from conservation and restoration of existing natural infrastructure,” Jones said. “Coastal ecosystems reduce the proportion of vulnerable people and infrastructure along exposed U.S. coastlines by around half through their absorption of wave energy.”

The study authors also pointed to other benefits of natural infrastructures, which provide habitats for a host of marine and terrestrial animals and create recreation and tourism opportunities. In the most vulnerable coastal regions alone, mangroves store at least 896 million metric tons of carbon.

“Ensuring the resiliency of mangroves is a win-win-win for people, nature and the climate,” said Dave Hole, co-author of the study and senior director within Conservation International’s Betty and Gordon Moore Center for Science.

“Mangroves store more carbon than any other forest ecosystem on Earth, drawing CO2 down from the atmosphere and storing it for decades, and so helping slow global warming,” he said. “As interest in ecosystem-based adaptation continues to grow, it’s vital that its multiple co-benefits are part of the conversation.”

Next step: site-specific studies

The authors noted that their global study provides “a coarse approximation” of threats and of regions of the world that might benefit most from ecosystem-based adaptation.

Despite mounting interest in ecosystem-based adaptation, implementation has mostly been in the form of site-specific projects. What’s needed next, the authors said, is systematic assessment of the broader potential, analyses of the ways in which ecosystem protection varies from site to site, and further investment in conservation and restoration.

“It’s a relatively new option that’s gaining more traction,” Jones said. “Beyond engineering solutions, there are these ecosystems that have been providing benefits to us for centuries. They’re worthy of our attention and resources.”